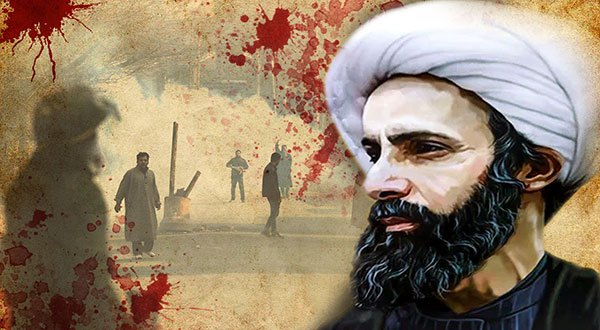

Two years have passed since the execution of the martyr Sheikh Nimr Baqir al-Nimr, who was arrested by the Saudi authorities in August 2012 and executed on January 2, 2016. It was not enough time for the regime to turn the page on the Sheikh who shook the halls of power with his words. Authorities have always considered the residents of the Eastern Region – precisely the Qatif Governorate – as third or fourth class citizens. The problem of the regime is not with the martyred Sheikh but with his ideas, as it undermines its project for the region from which he hails.

Sheikh Nimr Baqir al-Nimr was not the first rebel from Saudi Arabia’s eastern region. But he may be the last. Researchers specialized in the history of that region understand well that al-Nimr inherited a large stock of the his ancestors’ and the people of his region’s struggle and engraved it with his knowledge and daring, courageous personality. He disseminated it among the people of his region and the rest of the popular segments in the kingdom of the House of Saud. Rejecting oppression and domination and demanding civil, political and economic rights were among the most prominent things that the martyred Sheikh addressed in his speeches and lectures. The Sheikh did not carry a gun to attain his rights and did not call for an armed revolution. He always repeated his famous phrase: “The word is stronger than the whiz of the bullet.” What disturbs the Saud family – regardless of who is ruling – is someone questioning the legitimacy of their rule, confronting them with the reality of their domination and demanding that they give each person their rights. Thus, they mobilize to silence the voice of truth. That is what the Sheikh repeated and focused on, eventually paying with his life.

Since his execution in 2016, the Saudi regime has not missed an opportunity to try to obliterate and distort his memory. The pretext for the invasion of Awamiya last May was that his “armed” supporters were holed up in the historic neighborhood of Masoura (his hometown). Before the invasion began, the Saudi interior ministry armed its entire media and mobilized its propaganda arms to prepare the historic incubator of the regime and to ship it to keep pace with the campaign.

During the three-month invasion of Awamiya, it was clear from the photographs and videos taken by the interior ministry’s special force and their patrols that the central objective of the campaign was to reach the Husseiniya [a congregation hall for Shiite commemoration ceremonies], where Sheikh Nimr al-Nimr used to address the people of his area and his supporters. The soldiers who displayed vengeance inside mosques exhibited the level of racism and sectarian hatred through their comments and actions. The objective was not to expel outlaws and “terrorists” who prevented the implementation of the development of the Al-Masoura neighborhood as the regime’s media claimed. But rather to infiltrate an atmosphere inaugurated by Sheikh al-Nimr in his area, which inspired the people of many cities and villages in the Eastern Province.

The Scheme to Dismantle Qatif

Qatif, Awamiya and the surrounding villages can be described as a historically intractable case for the Saudi regime. The area was placed under the rule of Al-Saud in 1913 after the Al-Ahsa Governorate. The regime did not change its view of the population of that region as the years passed. In an interview in 1996, an American doctor, Richard Daghi, recalls the time when he was working on a health program for Aramco in the early fifties to raise awareness among the residents of Qatif on ways to prevent smallpox. He wanted to play an awareness film for the residents of the Safawi village. The then Emir of the Eastern Province, Saud bin Abdullah bin Jalawi Al-Saud, denied his request to show the film, saying: “if God does not want the people to be infected with smallpox, he would not have sent them smallpox (1)”. This inherent racism in the hearts of the princes of the Al-Saud is later translated into actions taken by the regime against the people of Qatif. Last year, researcher and rights activist Adel Al-Saeed, who hails from Qatif, published a study titled “A Study on the Residential Crisis in the Province of Qatif in Saud Arabia (2)”. In it, he highlights the features of a project targeting Qatif and its inhabitants. The project entailed restricting urban expansion in the province by creating conditions that would eventually drive the locals from the area.

Since the 1920’s, the regime was able to make a demographic change in al-Ahsa by attracting residents from the central region of Najd and from the south in Asir. This contributed greatly to the regime taking control of the province. It also made it a starting point to encircle Qatif, harass the residents through the services, annex their lands and append them to other surrounding governorates. In his study, Al-Saeed said that the Saudi government does not respond to the fact that the population is growing in parallel with the rise in the number of young people eligible for marriage and the urgent need to secure new housing. When it comes to the plans of the ministry of housing, the study shows that Qatif is given the lowest percentage among the provinces of the eastern region amid a growing number of complaints from the residents whose lands have been either annexed, seized, and assigned to other provinces such as Dammam, Jubail and Ras Tanura. Other lands have been granted to the princes and their inheritors. Meanwhile the boundaries of the lands allocated to Aramco projects, which are called “Aramco Reservations”, are expanded at the expense of the owners of the land.

This reality is not new. The housing crisis fabricated by the regime in the province of Qatif dates back decades in parallel with the media and security campaigns targeting the residents of the region which is continuing. After the Muharram uprising of 1980, former Interior Minister Nayef bin Abdul Aziz worked to demonize Qatif and issued accusations against the province’s iconic figures that worked to educate its sons about their looted rights. The regime decided that accusing the residents of the area – who are merely demanding their rights – of being connected to Iran and the Islamic revolution will justify all the measures that are part of the plan to dismantle the movement that is opposed to the official Saudi policy of repression and tyranny. The leaders and activists of Qatif’s popular movement were incarcerated in the late 1980s. The prosecution campaigns have continued since then until the interior ministry’s prisons were filled with these iconic figures. These methods adopted by the regime were accompanied by attempts to contain and attract the iconic and the not so popular figures among the population, including Sheikh Mohammed al-Jirani, who was kidnapped from the front of his home in Tarot in mysterious circumstances in December 2016. The fact that the man did not have a good relationship with the popular movement in his area prompted the security services of the regime to exploit the incident and accuse activists who participated in the 2011 and 2012 popular demonstrations of his assassination. The year 2017 saw dozens of activists in Qatif being accused of participating in the kidnapping of al-Jirani. Every few months, the Saudi interior ministry would announce the indictment of more young men over their alleged participation in the operation, until the number of those charged reached about 25 people without exaggeration. The announcement was often issued after the assassination of some of these activists. Of course, the purpose of the charges was to justify liquidating them in the field.

Al-Nimr is haunting them

Since the assassination of the martyred Sheikh Nimr al-Nimr, there has been a clear direction followed by the regime that can be described as the “Daeshanization of Qatif (3)”. This process is driven forward through the media, newspapers and on satellite channels, in addition to social networking sites. The electronic armies have also pumped tremendous incitement in this field, before and during the invasion of Awamiyah. And it still continues to do so.

The regime’s arms of propaganda tried to portray the dissidents in Qatif as being similar to “Daesh” in their “terror”. Events that took place in any community – even small ones – were exploited to promote this accusation, including the occasional rulings by Saudi courts against young demonstrators, which often involved the death penalty. The crime of these young people is their participation in the 2011 and 2012 popular demonstrations. Attempts to distort the image of Sheikh Nimr, who led the popular movement in 2011, continued even two years after his execution. Saudi newspapers controlled by the Saudi security apparatus published laughable headlines that insulted the readers’ intelligence. One example reads: “Iran’s Nimr assassinated al-Jirani, the denier of terrorism (4)”.

The Saudi media has resurrected martyr Sheikh Nimr al-Nimr two years after his execution, accusing him of being behind the killing of al-Jirani. Yes, the thought is fictional and ridiculous, but this is what the Saudi regime’s media is bestowing upon us from time to time when it comes to its desperate attempt to liquidate the free voice.

1- Interview with Dr. Richard Daghi – Chief of Preventive Medicine at Aramco 1947-1964

2- Study of researcher Malik Al-Saeed “Study in the residential crisis in the province of Qatif in Saudi Arabia” -2017

3- D. Hamza al – Hassan – “Beyond the Daeshanization of Qatif… A decaying regime and opportunistic politicians” – November 2016

4- Okaz 28/12/2017 – “Iran’s Nimr assassinated al-Jirani, the denier of terrorism”

Source: Al-Ahed

Source Article from https://uprootedpalestinians.wordpress.com/2018/01/04/al-nimr-hit-the-project-for-dismantling-qatif-and-returned-to-haunt-them/

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

January 4th, 2018

January 4th, 2018  Awake Goy

Awake Goy  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: