In November 1954, freedom fighters in Algeria, which had long been occupied by the French, launched a war of liberation against their occupiers. Two of those happiest to hear this news were Zohra Drif and her close friend Samia Lakhdari, both of them young Algerian students at the (French) Faculty of Law in the capital, Algiers. Samia and Zohra tried several times to contact the activists of the “National Liberation Front” (FLN) and its armed wing the “National Liberation Army” (ALN), but because of the depth of the French repression the independence activists were forced to work with tight operational security. Contacting them was hard! In November 1955, Zohra and Samia succeeded in establishing contact, and for the following months, using their ability to “pass” as Frenchwomen when necessary, they acted as couriers for the militants.

Djamila Bouhired (R) and Zohra Drif (L). (Photo: Just World Books)

In summer 1956, the French-colonial “ultra” vigilantes considerably increased their level of violence against the Algerian population and any French settlers suspected of sympathizing with them. Samia and Zohra pleaded with their male ALN contacts to allow them to take part in the armed struggle, arguing that precisely because of their ability to “pass” as French, they could reach targets that would be hard for male fighters to reach. That August, the ALN’s male hierarchy acceded to their request and they joined a small trusted force of female fighters who also included Djamila Bouhired.

Samia Lakhdari. (Photo: Just World Books)

In September 1956, the three young women each planted a bomb in a location used by numerous civilians from among France’s then-million-strong population of settlers in Algeria. Zohra’s bombing, in particular, lay at the heart of the story later made into the iconic film “The Battle of Algiers”. The reprisals undertaken by the French authorities and the ultras were extremely fierce. Djamila Bouhired was arrested the following spring, and in September 1957 Zohra Drif and Samia Lakhdari were arrested.

When Algeria finally won its independence in 1962, all the Algerian political prisoners were released. Zohra Drif was elected to the first Algerian parliament and married a fellow ALN fighter, Rabah Bitat, who in 1978 briefly became Interim President of Algeria. In 2016, Mme. Drif retired from her service as Vice-President of the Algerian Senate.

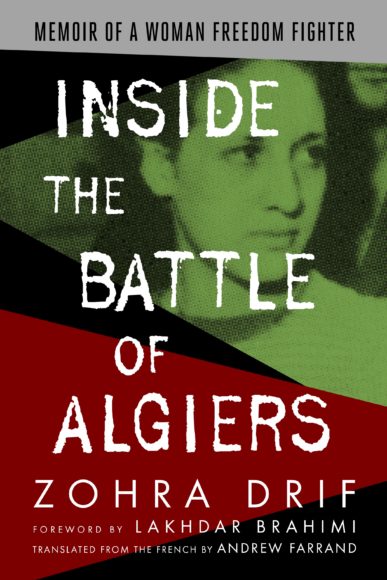

She originally published her memoir of her time as freedom struggler a few years ago, in French. The new English edition has been translated by Andrew Farrand and has a Foreword from the distinguished Algerian diplomatist Lakhdar Brahimi. In this excerpt, Zohra Drif reflects upon her decision to join the armed struggle in 1956.

***

I need to explain why our induction into the armed groups was, for us, more than just the result of a desperate search, but an immense honor that “the brothers” bestowed upon us. We read a lot and were very influenced by the writings of the Bolshevik Revolution, the Spanish Civil War, and the anti-Nazi resistance. We read and reread Democracy in America by De Tocqueville and had understood, ever since the end of high school, the fate that France hoped to relegate us to: the same as that of the Native Americans.

This is what France had wanted to do in Algeria with its policy of conquest via massacres, genocides, and smoke-out exterminations, then its policy of colonization via forced dispossession against the Algerian population and their replacement by European settlers. To do all this, France mobilized its imperial army, the Warnier law, the Senatus-Consulte, and its Native Code—which, despite its repeal in 1947, was still in force in 1956. Samia and I had always been convinced that if France hadn’t yet imposed the American Indians’ fate on us, it wasn’t because she didn’t want to, but because she wasn’t yet able to. This was because our people had always resisted, from Emir Abdelkader to Fatma N’Soumeur, from Boubaghla to Cheikh Al Haddad and El Mokrani, from Bouamama up to Zâatcha, and so on.

Our nineteenth century was one of mass slaughter that made rivers of our ancestors’ blood flow, thousands of hectares of their land burned and seized, and countless cities, towns, and villages ransacked and set alight. Our twentieth century was no better; the massacres of May 8, 1945, and August 20, 1955, ended up serving as fuel for the fire that our brave combatants lit on November 1, 1954, and that would not be extinguished until our country’s liberation, and rightly so. We had always believed that our misfortune, our bondage, our negation as a people and nation went hand in hand with the system of settler colonialism.

As a result, we always believed that our liberation and our affirmation would come with the end of colonization. We had always considered it better to die with honor in the armed struggle for dignity and liberation than to survive in the disgrace of tolerating colonization—and by settlement, at that. Liberty, dignity, and honor: three supreme values, three inalienable rights defined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

But France recognized none of these rights for us, a colonized people reduced to “native” status. Does this mean that for France, this so-called “Mother of Arts, of Weapons, and of Laws,” we weren’t human beings? It seems we were not! Never was our people’s status as human beings in our own right, with the sacred rights that went with it, considered or even suggested. At best, they saw us as idle hands for whom someone needed to create a few more jobs, and empty bellies to whom someone needed to throw a few more scraps. Could the “natives” desire freedom and dignity like all peoples? Could we commit to these values, even to the point of making the supreme sacrifice? That was what we held as more than just an ideal, it’s what shaped our souls and our deepest beings in 1956, as it does today.

In a free and independent country, these questions could be a harmless intellectual concern for a student thesis. For Samia and me they constituted a life-or-death issue, individually and collectively. And even when viewed with a critical eye, we considered (and still consider) that only those who had “tasted” the colonial system as we had could respond to it.

Take a young Patrice Lumumba, whose body, soul, and country were subdued, enslaved, and colonized, and compare him with a Belgian or a European of the same age whose body, soul, and country were free and independent, and ask them the same questions. Or, if you prefer, summon the souls of Mahmoud Darwish and his people’s Israeli colonizers, and ask them the same questions. Or, if you like, summon Federico García Lorca from Spain or Aminatou Haidar, the noble Saharawi activist whose people and country are still occupied by Morocco, and ask them the same questions. I could go on like this at length, since, sadly, there still exist peoples and countries deprived of their rights. But what I know already is that a deep sense of honor and attachment to this greatest of values—freedom— would prohibit any dignified and honorable person from engaging in such question games if he or she has never lived in the cynically abject and unfair conditions I have described above.

But those were precisely the conditions in which we Algerians lived in 1956 and in which we had lived for 126 years. That was why, knowing the stakes full well in our hearts and souls, Samia and I made the choice to become “volunteers for death”—“bombers” or bombistes, as they would later call us.

Perhaps the reader of today expects me to regret having placed bombs in public places frequented by European civilians. I do not. To do so would be to obscure the central problem of settler colonialism by trying to pass off the European civilians of the day for (at best) mere tourists visiting Algeria or (at worst) the “natural” inheritors of our land in place of its legitimate children. I will not adopt this position because I hate lies and their corollary, revisionism, whatever they are and wherever they come from. Samia and I did not regret our actions in 1956 or 1957, nor do we today, nor will we ever. I speak here in my own name and on behalf of my friend and sister Samia Lakhdari, who died in the summer of 2012. What’s more, if today, God forbid, my country were to be attacked and occupied by a foreign force, I know that even at my advanced age, propped up on a cane, I would be with all those (and I know there are many of them, in Algeria and elsewhere) who would offer their lives to liberate our land and its people. In declaring this, I seek neither to boast nor to challenge anyone. I am simply trying to convey an idea, a simple conviction related to the concept of responsibility.

In August 1956, Samia and I, assuming full responsibility, chose to become “volunteers for death” to recover and free our mother, Algeria— who had been taken by force, raped, and kidnapped for 126 years—or to die. Faced with the choice between our mother and our lives, like Camus, we chose our mother. Yet in truth, we did not face the same dilemma as Camus, who, ordered to choose between justice and his mother, sacrificed justice. In fact, his mother being his country, France, as a colonial power she was antithetical to justice.

Our own mother being Algeria, her liberation was one and the same with justice.

As for the civilians who perished during the war of national liberation, if they are Algerian, I would propose that they go to the ALN fighters and ask them, “Why did we die?” I know that the ALN will reply, “You are dead because your lives were part of the price we had to pay for our country to be free and independent.”

And if they are French, I would propose that they go see the French authorities and ask, “Why did we die?” I do not know what the French authorities would say, but I would propose to them the one real truth there is: “You died because you were among the hundreds of thousands of Europeans that we used to subjugate and occupy a foreign country, Algeria, so that we could make it our settler colony.”

In any case, this will not make me forget all the French who chose justice and the values of freedom and dignity (of which their own homeland boasted) and joined our camp. I will be eternally grateful. I will not finish this long and necessary clarification without affirming my deep conviction: The only case where a people has the right and duty to take up arms is when its country and territory are attacked by an external force. This is called self-defense. That was our case in November 1954 and throughout our struggle.

Excerpt from Inside the Battle of Algiers: Memoir of a Woman Freedom Fighter by Zohra Drif (Just World Books, 2017.) This excerpt is published here under a Creative Commons license by kind permission of Mme. Drif and Just World Books.

Zohra Drif will be reading from her memoir in New York City at three events:

- Tuesday, Sept. 26, 7 p.m.: A community dinner in the East Village, at Nomad Restaurant, 78 2nd Av (between 4th & 5th Sts.) Space is limited. Please reserve your seats by contacting Hamid Kherief.

- Friday, Sept. 29, afternoon or early evening: A book talk/discussion at Columbia University. Details t.b.d.

- Sunday, Oct. 1, 6 p.m.: Mme. Drif to be honored at a Palestinian-American community event and film screening at Anthology Film Archives, 32 2nd Av (also in the East Village.) Details and tickets here.

And she will be speaking on Monday, Oct. 2, 2017 at Harvard University from 4:00 p.m. – 5:30 p.m.

Source Article from http://mondoweiss.net/2017/09/between-excerpt-freedom/

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

September 26th, 2017

September 26th, 2017  Awake Goy

Awake Goy

Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: