“In 1949, in the city of Montreal, Canada, Peter Green created the first ever blister sealing machine for retail packaging. Peter, the inventor of the rotary blister-pack seal unit, was the pioneer and originator of the blister packaging machine. Through countless hours, hard work, and experimentation, he finally perfected the chemical relationship between board, and P.V.C.

“Peter Green’s main goal behind blister packaging, was to prevent pilferage. As well as being an excellent marketing tool, overtime it has become a highly preferred packaging method. A visually appealing package gives maximum product identification to the consumer.”

But there’s a problem. “Product packaging generates more plastic waste than any other industry. In Europe, it accounts for 59 percent of all plastic waste by weight. In the United States that is likely closer to 65 percent, experts say. The global packaging market is a $700-billion-a-year industry and growing at 5.6 percent per year. Plastics account for one-third of this, making packaging the largest single market for U.S. plastics.

“Clamshells, like most packaging, are single-use plastics and while technically recyclable, few are recycled in the U.S. That needs to change quickly if product manufacturers and the plastics industry are to meet their commitments to recycle or recover all plastics and greatly increase their use of recycled plastic in packaging.”

“Since the 1970s, when litter was of a significant concern, packaging has often been associated with wasteful behavior. This is partly due to the fact that packaging wastes are a very visible part of environmental problems. The negative image of packaging does not, however, translate into consumer hostility at point of sale. Products and not packages are bought. The package is not noticed during purchase, transport, and use of the product—in fact, it is not noticed until the minute the product is consumed and the package has fulfilled its function and turns into waste. At that minute, the package is already seen as an environmental burden, wasting resources. Those concerned about the state of the environment can take part in reducing this burden through packaging recovery programs.”

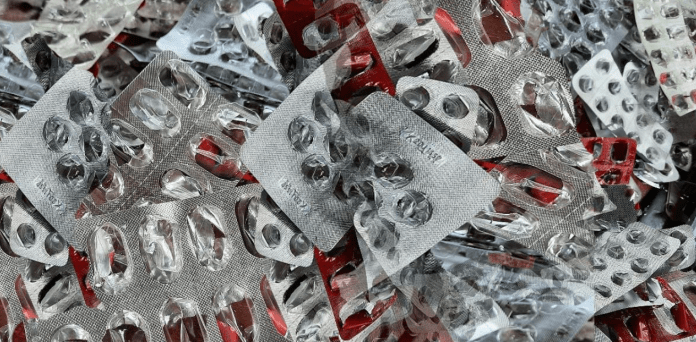

“Among the materials used for pharmaceutical packaging, polymer and aluminum are the most common materials used at the industry level. Pharmaceutical blisters represent the leading segment of the medical packaging market in Europe and Asia, contains an average of 10-20 wt.% of aluminum foils and 80-90 wt.% of the polymer. In Europe alone, 85% of solid drugs are packed in blisters. Globally, the market size of blister packaging was estimated at USD 17.76 billion in 2018 and is projected to reach USD 24.25 billion in 2024 at a CAGR of 6.3%.

“Pharmaceutical blisters have a very complex structure of polymers and metals. The aluminum-polymer layers are joined together using a bonding agent, which makes the separation between metal and polymer layer challenge. Therefore, due to the structural complexity and challenge in the separation process, pharmaceutical blister packages are not accounted for aluminum recycling and mainly disposed of along with household waste by incineration or landfilling.

“This causes not only the loss of aluminum from the circulation of metals but also contributes to environmental pollution. Although there are a few attempts to separate aluminum and polymer fractions from blisters using chemical, mechanical and thermal processes, however, most of the current solutions are not sustainable due to high-energy consumption, use of chemicals and harsh conditions.”

“Since the 1990s, water contamination by pharmaceuticals has been an environmental issue of concern. Many public health professionals in the United States began writing reports of pharmaceutical contamination in waterways in the 1970s. Most pharmaceuticals are deposited in the environment through human consumption and excretion, and are often filtered ineffectively by municipal sewage treatment plants which are not designed to manage them. Once in the water, they can have diverse, subtle effects on organisms, although research is still limited. Pharmaceuticals may also be deposited in the environment through improper disposal, runoff from sludge fertilizer and reclaimed wastewater irrigation, and leaky sewer pipes. In 2009, an investigative report by Associated Press concluded that U.S. manufacturers had legally released 271 million pounds of compounds used as drugs into the environment, 92% of which was the industrial chemicals phenol and hydrogen peroxide, which are also used as antiseptics. It could not distinguish between drugs released by manufacturers as opposed to the pharmaceutical industry. It also found that an estimated 250 million pounds of pharmaceuticals and contaminated packaging were discarded by hospitals and long-term care facilities. The series of articles led to a hearing conducted by the U.S. Senate Subcommittee on Transportation Safety, Infrastructure Security, and Water Quality. This hearing was designed to address the levels of pharmaceutical contaminants in U.S. drinking water. This was the first time that pharmaceutical companies were questioned about their waste disposal methods. No federal regulations or laws were created as a result of the hearing. Between the years of 1970-2018 more than 3000 pharmaceutical chemicals were manufactured, but only 17 are screened or tested for in waterways.” Alternately, “There are no studies designed to examine the effects of pharmaceutical contaminated drinking water on human health.” In parallel, the European Union is the second biggest consumer in the world (24% of the world total) after the USA and in the majority of EU Member States, around 50% of unused human medicinal products is not collected to be disposed of properly. In the EU, between 30 and 90% of the orally administered doses are estimated to be excreted as the active substances in the urine.”

Blister packaging combining aluminum and plastics creates an enormous amount of pollution. The problem with blister packaging is that the waste cannot be readily recycled. Nor can it readily be burned, as other plastic might. But what is the benefit of blister packaging? “With about 80% of U.S. pharmaceutical products today being delivered and dispensed in bottles, [one writer claims that] there is a huge opportunity to utilize more blisters and have a meaningful impact on: the environment, product quality, child safety and patient outcomes through improved adherence.”

But others disagree. “As drug prices continue to rise, here’s a helpful cost containment tip to share with plan members who take maintenance medications: Beware of blister packs.

“Blister packs are a type of pre-formed, plastic packaging that seal individual tablets until they are taken.

“Blister packs can enhance the integrity of the medication by improving shelf life and providing a barrier against tampering. For individuals who have trouble determining when or how much medication to take, weekly blister packs can help prevent accidental overmedication, as doses can be separated and marked for specific days.

“However, unless recommended by a physician or a pharmacist, blister packs may not be necessary, especially for maintenance medications that can be filled in 90-day supplies. For maintenance medications, weekly blister packs can significantly increase costs to plans and plan members.

“Pharmacies charge a dispensing fee each time they fill a prescription. One weekly blister pack is considered one prescription fill. To obtain a 90-day supply, a plan member would require 12 blister packs and pay 12 dispensing fees, as opposed to a single dispensing fee for one 90-day supply. Consider the following example for a plan member who takes three maintenance medications, and has these filled at a pharmacy with an $11.75 dispensing fee per prescription:

- Weekly blister packs: 3 maintenance medications x 12 weekly fills x $11.75 = $423.00

- 90-day supply: 3 maintenance medications x 1 90-day fill x $11.75 = $35.25”

In other words, there are some advantages to blister packaging. For instance, children are less likely to take medicines that harm them in a blister pack than in a bottle. But when you weigh that risk together with the environmental risks, using bottles are better. If medicine bottles were standardized so that they could be returned to pharmacies and used over and over again, that would help the environment problem.

We should probably go back to the system of using deposits for bottles of all sorts. Even if the deposit is only $.25, the existence of the deposit strongly encourages the user to bring back the bottle and collect the deposit. If the user doesn’t do it, then homeless people are likely to try to find the bottles in the trash and get the money. Either way, the environmental impact is lessened, and today that’s a very important thing.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

July 23rd, 2021

July 23rd, 2021  Awake Goy

Awake Goy

Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: