In days of old, the dead were buried with a silver coin (the shiner the better) so that the souls of the faithful departed could pay the toll to the deathless demon ferryman of the underworld: Charon. Son of Darkness and Night, Charon grimly rows back and forth across the River of Woe bringing the newly dead to their eternal hereafter in Hades. The only joy in his job is the opportunity to push coinless or improperly buried souls out of his boat and into the deep below. The only break in the monotony of his task is the appearance of undead travelers such as Aeneas and Dante.

Charon’s Parents

Born of Chaos, Nyx is the Goddess of the Night. So great and powerful was her beauty that even Zeus, King of the Gods, stood in fear of her. It is believed that Nyx stood at the creation of the universe and chanted while Adrasteia (also known as Nemesis) clashed cymbals, beat drums, and danced the heavens into their proper place. Some say Adrasteia is the daughter of Nyx alone, others say she is the daughter of both Nyx and Erebus, God of Darkness and Shadow.

The Night. Marble relief by Bertel Thorvaldsen. ( Public Domain )

Little is known about Erebus. According to Hesiod, the ancient Greek poet, Erebus is one of the five primordial deities that existed at the dawn of the universe. The first of the five is Chaos, the sexless Void believed to have brought forth the other four primordial deities: Erebus, Nyx, Aether (Light) and Hemera (Day). As the personification of darkness, Erebus can be found in deep shadows and on moonless nights. In Greek literature, he is most explicitly described as personifying the region a soul enters immediately after they die but before they arrive at the world of the dead.

The Ferryman

Charon was born from the union of Erebus and Nyx in a time before recorded thought, along with his siblings or half-siblings Thanatos (Death), Ker (Destruction), Moros (Destiny/Doom), Hypnos (Sleep), the Moria (Fates), and Geras (Old Age). Charon’s name is a poetic variation of charopós, which means “of keen gaze”. Most probably, this refers to the bright or feverish eyes of a person close to death. The description also reflects the cross nature of the ferryman.

Charon ferries souls to the Styx River. ( Massimo Todaro /Adobe Stock)

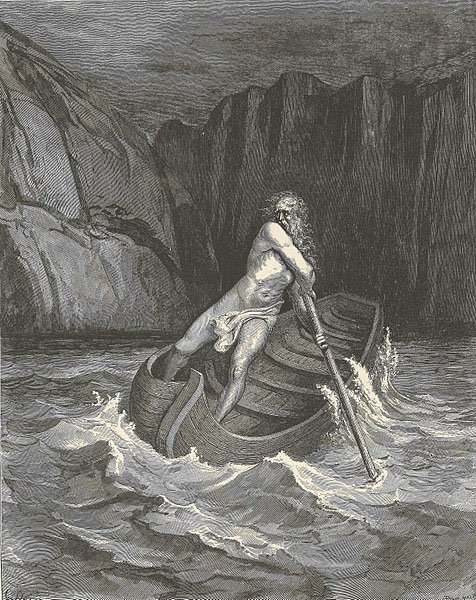

For example, Dante describes him as “Charon the demon, with eyes of glowing coals” (Hollander, 53, 2000). In Virgil’s Aeneid, another famous visitor to the Underworld, Aeneas, describes the ferryman in greater detail:

“And here the dreaded ferryman guards the flood,

grisly in his squalor— Charon…

his scraggly beard a tangled mat of white, his eyes

fixed in a fiery stare, and his grimy rags hang down

from his shoulders by a knot. But all on his own

he puts his craft with a pole and hoists sail

as he ferries the dead souls in his rust-red skiff.

He’s on in years, but a god’s old age is hale and green.”

(Virgil, 192, 2006)

Charon is frequently described as ragged, ugly, gloomy, and dirty; however, he appears in more literature than his parents or any of his siblings.

Charon, The Ferryman of Hell by Gustave Dore (1880) (Public Domain )

One of his earliest mentions is in the Greek satirical tragedy Alcestis by Euripides: “Alkestis [Alcestis] : I see him there at the oars of his little boat in the lake, the ferryman of the dead, Kharon [ Charon], with his hand upon the oar and he calls me now. ‘What keeps you? Hurry, you hold us back.’ He is urging me on in angry impatience.” (Atsma, 2016) Other Greek stories explain how it is the Moria (Fates) who are irritably summoning Charon to bring them their due.

According to ancient Greek custom, the deceased should be properly buried with a silver coin under their tongue. The departed souls would fly to Hades, sometimes accompanied by the Messenger of the Gods, Hermes. They would arrive on the far shores of the Acheron, the River of Woe.

Those who were properly buried and provided coins could pay their fare across the river; those who were not buried or who had not been provided with ferry fare were forced to wander the far shores of Hades for 100 years.

Although primarily known for conveying shades to the gates of Hell , there are five rivers in the Underworld that Charon could journey: “Acheron, Cocytus (the river of lamentation), Phlegethon (the river of fire), Lethe (the river of forgetfulness), and finally, Styx (the hateful river)” (Encyclopedia of Death and Dying, 2016).

Top image: A 19th-century interpretation of Charon’s crossing by Alexander Litovchenko. Source: Public Domain

Updated on November 27, 2020.

References:

Alighieri, Dante. Inferno. Trans. Robert Hollander and Jean Hollander. New York: Anchor, 2002. Print.

Aquileana. “Charon, Ancient Greek God of The Underworld.” La Audacia De Aquiles. La Audacia De Aquiles, 26 Apr. 2014. Web. 30 July 2016. https://aquileana.wordpress.com/2014/04/26/mythology-charon-ancient-greek-god-of-the-underworld/

Atsma, Aaron J. “Kharon.” Charon (Kharon). Theoi Project, 2016. Web. 30 July 2016. http://www.theoi.com/Khthonios/Kharon.html

Atsma, Aaron J. “Primordial Gods.” Primordial Gods & Goddesses. Theoi Project, 2016. Web. 30 July 2016. http://www.theoi.com/greek-mythology/primeval-gods.html

Encyclopedia of Death and Dying. “Charon and the River Styx.” Death and Dying. Encyclopedia of Death and Dying, 2016. Web. 30 July 2016. http://www.deathreference.com/Ce-Da/Charon-and-the-River-Styx.html

Virgil. The Aeneid. Trans. Robert Fagles. New York: Viking, 2006. Print.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

November 28th, 2020

November 28th, 2020  Awake Goy

Awake Goy  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: