Chelsea Football Club, in partnership with the Jewish News and renowned British Israeli street artist Solomon Souza, on Wednesday launched the exhibition “49 Flames – Jewish Athletes and the Holocaust”. WWII-ear Jewish athletes featured on a mural

WWII-ear Jewish athletes featured on a mural

WWII-ear Jewish athletes featured on a mural

WWII-ear Jewish athletes featured on a mural Last year, Chelsea owner Roman Abramovich commissioned Solomon Souza to create a commemorative mural of Jewish soccer players who perished during the Holocaust. The final piece was presented during an event at Stamford Bridge observing Holocaust Memorial Day 2020.

The club has now worked with Souza to develop an extended exhibition featuring Jewish athletes who were killed by the Nazis during the Second World War. The art installation and virtual exhibition is part of Chelsea FC’s Say No to Antisemitism campaign and funded by club owner Roman Abramovich.

The name “49 Flames” refers to the number of Olympic medalists who were murdered during the Holocaust.

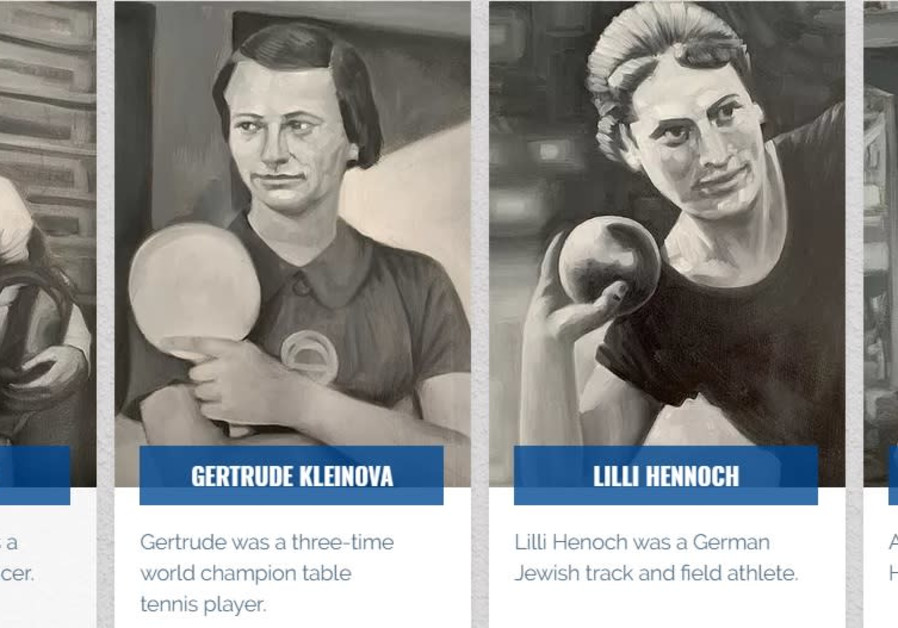

The exhibition aims to tell the story of the Holocaust through the eyes of Jewish athletes. Of the 15 athletes featured, profiles include Alfred Flatow and Gustav Felix Flatow, German Jewish gold medalists at the first modern Olympics held in Athens in 1896. The cousins, both gymnasts, would die of starvation in the Theresienstadt concentration camp. Also featured is German Jewish track and field athlete Lilli Henoch, who set four world records and won 10 German national championships.

The exhibition includes contributions from leading voices against antisemitism from around the world such as President Reuven Rivlin, Natan Sharansky, UK Government Antisemitism Adviser Lord John Mann, Lord Ian Austin, Karen Pollock of the Holocaust Educational Trust, Jewish Agency Chairman Isaac Herzog, Holocaust survivor and weightlifter Sir Ben Helfgott, The Anti-Defamation League’s Sharon Nazarian and others.

Below are profiles and voices against antisemitism. For more information, visit the exhibition here.

cnxps.cmd.push(function () { cnxps({ playerId: ’36af7c51-0caf-4741-9824-2c941fc6c17b’ }).render(‘4c4d856e0e6f4e3d808bbc1715e132f6’); });

if(window.location.pathname.indexOf(“647856”) != -1) {console.log(“hedva connatix”);document.getElementsByClassName(“divConnatix”)[0].style.display =”none”;}

Lilli Henoch

German Jewish track and field athlete who set 4 world records and won 10 German national championships, in four different disciplines. On September 5, 1942, Lilli Henoch and her mother were deported to Riga where they were both murdered by the Nazis.

Otto Herschmann

Austrian Jewish swimmer, fencer, lawyer, and sports official. He won a silver medal in the initial modern Olympic Games in 1896 for the men’s 100-meter freestyle and another in the 1912 Summer Olympics in fencing. He was persecuted for being Jewish by the Nazis and in 1942 was arrested and deported to the Sobibór extermination camp, and then to the Izbica concentration camp, where he was killed.

Antal Vágó

Hungarian Jewish international footballer who played as a midfielder. Vágó played club football for MTK for 12 seasons, winning the league nine times. Vágó was killed during the Holocaust, some claim that he was shot into the river Danube in late 1944 along with thousands of other Budapest Jews.

András Székely

Hungarian Jewish swimmer who won a European title in the 4 × 200 m freestyle relay in 1931 and then went on to win bronze in the same sport at the 1932 Summer Olympics. He was killed by the Nazis in 1943 at a forced labor camp in Chernihiv, Ukraine.

Anna Dresden-Polak & Judikje ‘Jud’ Simons

Dutch Jewish gymnasts who competed on the same team during the 1928 Summer Olympics. Anna and Judikje were two of five Jewish members of the team. All Jewish team members were killed during the Holocaust.

Eddy Hamel

American Jewish footballer for Dutch club AFC Ajax. In late 1942 Hamel and his family were detained by the Nazis. He spent four months doing hard labor at Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp after which he was sent to the gas chambers and killed.

Victor Perez

Tunisian Jewish boxer, who became the World Flyweight Champion in 1931 and 1932, fighting under his ring name “Young Perez”. On January 18, 1945, Perez was one of the prisoners on the death march from Monowitz in Poland, 37 miles or 62 kilometers northwest of the Gleiwitz concentration camp near the Czech border. Perez was reported to have been killed three days later on January 21. According to eye witness testimony he was shot to death by a guard while attempting to distribute bread he had found in Gleiwitz’s kitchen to other starving prisoners.

Bronislaw Czech

Polish Jewish sportsman and artist. A gifted skier, he won titles in Poland 24 times in various skiing disciplines, including Alpine skiing, Nordic skiing and ski jumping. A member of the Polish national team at three consecutive Winter Olympics, he was also one of the pioneers of mountain rescue in the Tatra Mountains and a glider instructor.

He took part in the Winter Olympics of 1928, 1932 and 1936. During the Second World War he was a soldier of the Polish Underground (Home Army) and courier from occupied Poland to the West. He was captured by Germans, imprisoned and murdered in the German concentration camp Auschwitz.

Roman Kantor

Polish Olympic epee fencer. In 1935 he contributed to the Polish victory over Germany. His achievements included a second place at the Open Championship of Lvov and being nominated to be a member of the delegation for the Olympic Games in Berlin in 1936, where he won seven bouts in the and four in the semi-finals. In 1942, Kantor was arrested and transported to the Majdanek concentration camp and killing center.

Attila Petschauer

Hungarian Olympic champion fencer. Petschauer was a winner of three Olympic fencing medals including two golds. Petschauer was arrested by the Nazis in 1943 and sent to a forced labor camp in Davidovka, Ukraine.

Oscar Gerde

Hungarian saber fencer who won team gold medals at the 1908 and 1912 Olympics. He was deported from Hungary in 1944 and killed that same year at the Mauthausen-Gusen Concentration Camp in Austria.

Alfred Flatow & Gustav Flatow

German Jewish Gold medalists at the first modern Olympics held in Athens in 1896. The cousins, gymnasts would die of starvation in the Theresienstadt concentration camp during the Holocaust.

Salo Landau

Polish born Dutch chess player who won the 10th Dutch National championship in 1936.. He was sent to a concentration camp in Gräditz, Silesia in November 1943, where he died sometime between December 1943 and March 1944.

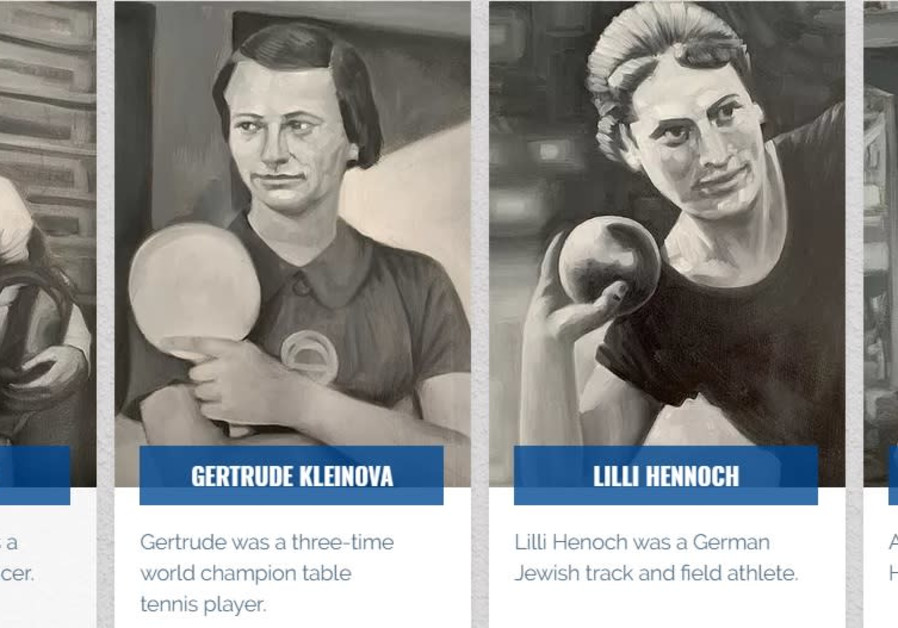

Gertrude Kleinova

A Czech three-time world champion table tennis player, winning the women’s team world championship twice, and the world mixed doubles once. Gertrude was deported by the Nazis to the Theresienstadt concentration camp and eventually sent to the Auschwitz concentration camp. Gertrude survived the horrors of Auschwitz and immigrated to the US after the war.

Lion van Minden

Dutch Jewish Olympic epee fencer, he competed in saber in the 1908 Summer Olympics in London, England, at 27 years of age. Van Minden was killed in the Auschwitz concentration camp in 1944.

Julius Hirsch, Arpad Weisz and Ron Jones

Julius Hirsch was a German Jewish international footballer who played for the clubs SpVgg Greuther Fürth and Karlsruher FV for most of his career. He was the first Jewish player to represent the German national team and played seven international matches for Germany between 1911 and 1913. He retired from football in 1923 and continued working as a youth coach for his club KFV. Hirsch was deported to Auschwitz concentration camp on March 1, 1943. His exact date of death is unknown.

Árpád Weisz was a Hungarian Jewish football player and manager who played for Törekvés SE in his native Hungary, in Czechoslovakia for Makabi Brno and in Italy for Alessandria and Inter Milan. Weisz was a member of the Hungarian squad at the 1924 Summer Olympics in Paris. After retiring as a player in 1926, Weisz settled in Italy and became an assistant coach for Alessandria before moving to Inter Milan. Weisz and his family were forced to flee Italy following the enactment of the Italian Racial Laws. They found refuge in the Netherlands where Weisz got a coaching job with Dordrecht. In 1942, Weisz and his family were deported to Auschwitz. Weisz’s wife Elena and his children Roberto and Clara were murdered by the Nazis on arrival. Weisz was kept alive and exploited as a worker for 18 months, before his death in January 1944.

Ron Jones, known as the Goalkeeper of Auschwitz, was a British prisoner of war (POW) who was sent to E715 Wehrmacht British POW camp, part of the Auschwitz complex, in 1942. Jones was part of the Auschwitz Football League and was appointed goalkeeper of the Welsh team. In 1945, Jones was forced to join the ‘death march’ of prisoners across Europe. Together with 230 other Allied prisoners he marched 900 miles from Poland into Czechoslovakia, and finally to Austria, where they were liberated by the Americans. Less than 150 men survived the death march. Jones returned to Newport after the war and was a volunteer for the Poppy Appeal for over 30 years, up until his death at the age of 102 in 2019.

Voices Against Antisemitism Featured in Exhibition

Frank Lampard, Manager Chelsea FC

It is hard to imagine that international football players today could be the victims of such persecution on the basis of their religion or ethnicity, but it did happen. The images of these three football players on our stadium serve as a reminder of that unthinkable past, and through this art exhibition featuring Jewish male and female athletes killed during the war, we hope to inspire future generations to always fight against antisemitism, discrimination and racism, wherever they find it.

Emma Hayes, Manager Chelsea FC Women

This is so important as we know that sport has not been immune to the horrors of the past. This exhibition brings back some of the darkest moments of our history. We see the Holocaust through the eyes of male and female athletes from around the world. The stories of Jewish athletes such as Lilli Henoch, Anna Dresden-Polak and Gertrude Kleinova remind us why we as a Club and individual sports professionals can never take our freedoms for granted.

Sir Ben Helfgott, Holocaust Survivor and Olympic medalist

As I was marching in the stadium during the opening ceremony, I kept thinking that not only was this a personal triumph for me, but I felt that I was representing all the potential Jewish sportsmen and women who could have been there had they not been killed by the Nazis.

President Reuven Rivlin, President of Israel

This book, honoring Jewish sportsmen and women whose lives were taken from them during the Holocaust while focusing on raising awareness about the evils of antisemitism in general and in sport in particular, highlights issues very close to my heart.

The efforts of the Chelsea Football Club, through the Chelsea Foundation’s Building Bridges Campaign, to raise awareness of the evils of antisemitism and other forms of racism in sport are therefore particularly welcome. As an avid football fan since childhood, I was pleased to be able to promote a program to combat all forms of racism in sports in Israel as part of the President’s Office’s flagship Israeli Hope project, and so was especially moved to read of the “Say No to Antisemitism” program being led by Chelsea Football Club.

Karen Pollack, CEO Holocaust Educational Trust

The history of the Holocaust is one of individuals, some of whom survived, but most of whom did not. Football unites people from different backgrounds and countries with a shared desire to win for their team. It is the deep shame of the history of football and the Holocaust. Ultimately when it came to it, the Jewish football star was regarded as ‘other’ and lesser and so deported, imprisoned, and murdered.

Andreas Hirsch, Grandson of footballer Julius Hirsch

The life and death of my grandfather teaches us that this can happen to anyone. A hero of war, a famous football player. If we let antisemitism and racism grow – anyone can become a victim. It is therefore our duty, to always stand up against antisemitism, racism and hate.

Isaac Herzog, Chairman of the Jewish Agency for Israel

My father, Chaim Herzog z”l, Israel’s sixth president, was a champion youth boxer in Ireland before he fought the Nazis as a Jewish officer in WWII. Jewish athletes represented many European countries in the early 1900s. For example, SC Hakoah Vienna, founded because Jews were banned from other clubs, produced several Olympic athletes and a competitive football team. Nazi Germany attempted to erase the tradition of Jewish athletes, who did not fit their narrative of the lazy Jew.

Sport is a powerful engine to combat hate and antisemitism. Sport can bridge cultures and foster tolerance. Yet the use of sport as a vehicle for hatred must end.

I’m therefore especially appreciative of Roman Abramovich for his efforts in the fight against antisemitism and his harnessing the impact of the Chelsea Football Club toward this noble goal.

Lord Ian Austin

It’s fantastic to see Israeli footballers playing in the British leagues and to see managers from the UK working with teams in Israel, but the opportunities for sport to promote ties that bring people together go so much deeper than that.

So, for example, it was wonderful to see His Royal Highness the Duke of Cambridge supporting a project bringing Jewish and Arab footballers together on his recent visit to Israel. One of the youngsters summed up the power of sport perfectly when he told our future king that “When you play football, you don’t have to talk the same language.”

Lord Sebastian Coe, President of World Athletics and International Olympic Committee (IOC) member

In the Berlin Games, Owens won four gold medals in the 100m, 200m sprint relay and long jump. And it was in the long jump where Owens was pitted against German Luz Long that sporting camaraderie and common decency trumped Hitler’s grand plan to use the Games as a platform for Aryan supremacy. In the competitions qualifying round Owens underperformed and was on the verge of missing the final. Long witnessed Owens’s plight and mid competition advised him to launch himself a foot shy of the take off board in order to qualify safely. His advice was given in the full realization that without Owens in the final, he was almost certain of leaving the Games as Olympic champion. Owens duly altered his run up, qualified and won a tight fought final against his German challenger. In the aftermath of competition both athletes embraced centre stage before an outraged Hitler who refused to shake the victor’s hand. It is a moment that distinguished sport and again exemplified its unique ability to transcend discrimination of any nature.

Lord John Mann, Independent Advisor to the UK Government on antisemtism

All discrimination, every racism is an issue for football. Antisemitism needs an equal recognition to all others, no more, but no less. It manifests in different ways and mutates into different forms. But the death of six million did not appear from nowhere.

In these difficult Covid times, the unifying passion of football has not surprisingly been immense in lifting people’s spirits. The Jewish community and especially young Jews are no different to anyone else in this.

By choosing to do nothing about antisemitism, a football club is making a statement about itself. About what its name, its badge, its shirt stands for. But by doing its little bit to combat antisemitism every football club is also making a clear statement. One that our club embraces everybody, that all are welcome, with no exceptions. That we value every supporter and every neighbor with equal respect. Each football club has a choice.

Lord Stuart Polak

It is often forgotten that as well as the six million Jews who were exterminated in the Holocaust, millions of other untermenschen (socially or racially inferior undesirables) were discriminated against and murdered by the Nazis. Another group regarded as enemies of the Third Reich – and thus open to discrimination and murder – were the various classes of Gypsies and Roma tribes. One such tribe were the Sintis, who were a Roma tribe in central Europe, and whose dialect of Sinti-Manouche exhibited a strong German influence.

The popular German Sinti boxer Rukeli “Johann” Trollmann was one of over 220,000 Roma and Sinti who died at the hands of the Nazis. Although his Sinti name was Rukeli, this was ‘Aryanised’ to Johann at school as his Sinti name was considered by the school authorities to

be undesirable. He was born in Hannover on 27th December 1907 and became a famous boxer in Germany before his retirement in 1934.

Richard Ferrer, Journalist and editor of Jewish News

The game even has a positive impact on perhaps the world’s most intractable conflict. Last year r I joined Chelsea’s women’s team on a pre-season tour to Israel where they took part in the remarkable Twinned Peace Sport Schools initiative that unites Arab and Jewish youngsters through football. The children play in mixed teams, learn about each other’s lives and culture and slowly overcome the ignorance that’s lead to more than 70 years of intolerance. After playing on the same side the children see each other as people rather than opponents. As one 11-year-old Palestinian girl from Jericho told me: “I don’t like the anger between Israelis and Palestinians, but I do like this. It makes me feel we have things in common.” Football, at its unique best, is an expression of all we have in common. It is the greatest equalizer.

Sharon Nazarian, Vice President Antidefamation League

Over the past few years, ADL Israel has joined forces with several partners in an effort to use soccer as a platform to bring people closer together to address discrimination and disrespect in soccer pitches across Israel. The most significant initiative is a LEAGUE OF RESPECT – a nation-wide initiative launched in 2018 which seeks to work holistically with soccer clubs around Israel towards lasting change. The basic assumption of the LEAGUE OF RESPECT is simple: in order to make a profound and sustainable change in any soccer club, all shareholders should be involved, from the club owner and management, to coaches, the youth players and their parents. Each has a unique role to play, which can create a ripple effect by spreading throughout the broader society at large.

Natan Sharansky, Human rights activist and author

During my nine-year in Soviet prison, the sport of chess was what helped me to keep my sanity. For over 400 days, I was placed in solitary confinement, where I would play thousands of games, against myself in my head. That is what allowed me to stay sane, even optimistic. I focused on my strong belief in the Jewish people as a powerful and unified community, even in the face of discrimination, and the deprivation of my very basic needs.

Olivia Marks Woldmann, Chief Executive of Holocaust Memorial Day Trust

We know how to admire sports men and women for what they do regardless of who we think they are; their merits break down barriers and teach us something about humanity beyond the narrow boxes of race, religion or origins. We can all learn so much from football. The sporting values apply soundly in Holocaust education and commemoration work. Holocaust education shows us a history when differences were feared, where communities were actively encouraged not to live and work together. That division started with prejudice and ended in gas chambers, concentration camps and six million Jews murdered in the Holocaust, as well as millions of non-Jews, including Roma people, black people, gay people – anyone different from Nazis’ idea of a master race – also murdered by the Nazis. Sport is teaching us something vitally important about ourselves – that we’re both stronger because of our differences, and that we are not all that different. That the same need to join in and belong beats in every heart, whether this heart is Jewish, Muslim, Christian or simply human without a label.

Tracy-Ann Oberman, Actress

I had one surviving great Uncle. He was called Josef. He escaped the Warsaw ghetto and was then picked up and taken to two concentration camps. I loved him. He spoke French with a thick Polish accent. I was in junior school and spoke schoolgirl French. When we visited him in his Paris apartment, he would sometimes show me the tattoo on his arm. He wouldn’t talk about his experience much. He was now one of France’s top psychiatrists. He even won the Legion D’honneur. He was a dude. But I remember asking him “how did the Holocaust happen?” And he replied, “because good people looked the other way.” I vowed never to be one of those people.

Related posts:

Russia’s Syrian Puzzle: How the West misread Putin

Musical intellectual and Jewish radical Jewlia Eisenberg dies at 50

Far-Left Jewish Group IfNotNow Holds Rally Against Biden Course on Antisemitism, Claims It ‘Won’t Ke...

Adam Grant and The Case for Nuance in Jewish Education

Dr. Tony Martin – Jewish Tactics In The Controversy Over Jewish Involvement in The Slave Trade

Former counter-intelligence chief has been warning about CIVIL WAR in France long before riots erupt...

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

December 10th, 2020

December 10th, 2020  Awake Goy

Awake Goy  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: