January 1st, New Year’s Day, is often ushered in with fireworks and festivities beginning on December 31st. Although this practice is the norm in many places around the world, not every culture has celebrated the start of a new year in this way, or necessarily on January 1st. There are many ways to honor the new year and several of them are based on ancient traditions.

The Bloodthirsty Beast Who Shaped the Chinese New Year

The Chinese New Year is one of the oldest extant traditions in the world. This holiday has been traced back as far as three millennia ago, with origins in the Shang Dynasty. In its earliest days, this festival was linked to the sowing of spring seeds, but it eventually found ties to a fascinating legend.

One popular version of the myth discusses the annual exploits of a bloodthirsty creature called Nian —now the Chinese word for “year”. To protect themselves and frighten off the beast, villagers decided to decorate their homes with red ornaments, burn bamboo, and make loud noises. The tactic worked, and bright colors and lights are still present in New Year’s festivities today.

These days, Chinese New Year celebrations involve food, family reunions, and the gifting of lucky money (usually in a red envelope), and the presence of several other red things for good luck. Lion and dragon dances, drums, fireworks, and firecrackers fill the streets on this day.

Dragon dance on Chinese New Year. (BigStockPhoto)

The use of the lunar calendar, a calendar dating to the second millennium BC, means that the Chinese New Year usually falls in late January or early February, on the second new moon after the winter solstice. The Chinese have linked each year to one of the 12 animals represented in the zodiac : the rat, ox, tiger, rabbit, dragon, snake, horse, goat, monkey, rooster, dog, or pig. In 2021, the Chinese New Year falls on February 12th and it is the year of the ox.

Rebirth in Nowruz – The ‘Persian New Year’

Nowruz (or Norooz) is the name given to the ‘Persian New Year’ – a 13-day long spring festival. Many of the traditions linked to this celebration have origins in the ancient past and are still practiced in Iran and other parts of the Middle East and Asia. The Persian New Year is celebrated on or around the vernal equinox in March.

This holiday is often associated with the Zoroastrian religion. The first accounts of Nowruz appear in the 2nd century, but scholars believe that it has existed since at least the 6th century BC. Nowruz is one of the few ancient Persian festivals to survive Iran’s conquest by Alexander the Great in 333 BC and the rise of Islamic rule in the 7th century AD.

This New Year festival was focused on the rebirth that accompanied the return of spring. Nowruz traditions include feasting, exchanging gifts with family members and neighbors, lighting bonfires, dyeing eggs, and sprinkling water – a symbol of creation. There have been changes to Nowruz customs over the years, but bonfires and coloring eggs remain popular in the modern version of the holiday, which is observed by an estimated 300 million people every year.

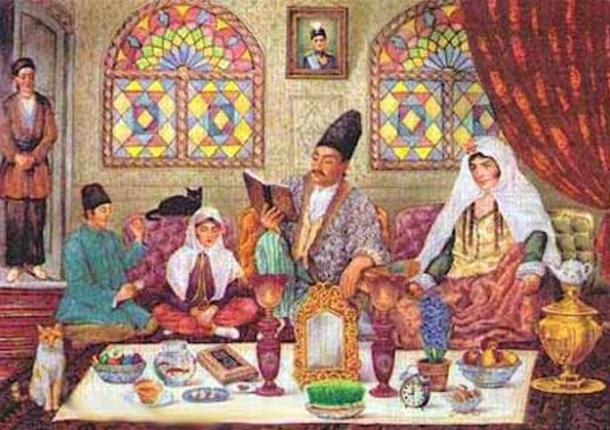

A painting representing a Qajar family gathering for Nowruz, and sitting around the Haft-Sin and probably reading Hafez. ( Public Domain )

The Sinhalese and Tamil New Year

Sri Lankan Sinhalese and Sri Lankan Tamils have separate New Year’s celebrations that fall on the same day. Aluth avurudda, the Sinhalese New Year, is held on April 13th or 14th and marks the end of the harvest season. There is the belief in an astrological time gap between the end of the old year and beginning of a new one. This occurs as the sun passes from the Meena Rashiya (House of Pisces) to the Mesha Rashiya (House of Aries) in the celestial sphere.

Buddhist rituals and customs and social gatherings and festive parties take place during this time. Gifts are exchanged, an oil lamp is lit, and rice milk is made during the Sinhalese New Year as well. Hindu households in Assam, Bengal, Kerala, Nepal, Orissa, Punjab, and Tamil Nadu also celebrate the New Year on April 14th or 15th.

A plate of Konda Kavum, a traditional Sri Lankan dish eating during New Year’s celebrations. It is a deep-fried sweet made with rice flour and treacle. (Chamal N/ CC BY SA 3.0 )

Ancient Egyptian Wepet Renpet

The Nile River was the lifeblood of ancient Egypt, so it is not surprising that their New Year corresponded with its annual flood. The New Year took place when the brightest star in the night sky, Sirius, was visible once again following a 70-day absence. This date often fell in mid-July just before the annual inundation of the Nile – an event which helped farmlands stay fertile for the following year.

The ancient Egyptians called the festival associated with this event Wepet Renpet, “opening of the year.” It was honored with feasts and religious ceremonies and was looked upon as a period of rebirth and rejuvenation.

During the reign of Hatshepsut, a “Festival of Drunkenness” took place in the first month of the year. Evidence for this event was uncovered at the Temple of Mut. The celebration has been linked to a myth in which the war goddess Sekhmet wanted to kill all humans, but was stopped when she was tricked into getting drunk by the sun god Ra. This was a huge festival celebrated with music, sex, and lots and lots of beer.

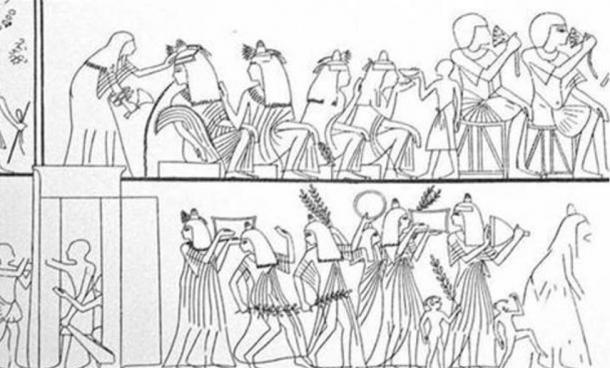

A drawing based on an ancient Egyptian wall painting shows a drinking festival in progress. ( Betsy Bryan )

When Sheba Returned: The Ethiopian Enqutatash

Enqutatash, the Ethiopian New Year, is celebrated on September 11th or 12th – the approximate end of three months of heavy rain. Mountains and fields are filled with blooming daisies at this time, and the old bless the young who anticipate new prospects. Traditionally this time of year has been linked to the return of the Queen of Sheba to Ethiopia after she visited King Solomon in Jerusalem in about 980 BC.

Large celebrations are held by almost all the cultures throughout the country. The festivities often start by the burning of a twig tree on New Year’s Eve. New Year’s Day begins with the slaughtering of animals and the blessing of bread and Tella (a traditional brew).

Enqutatash is the Ethiopian New Year. ( CC BY SA )

The Scottish Hogmanay

The Scottish have a particular way of celebrating the New Year. They call the holiday Hogmanay and it provides evidence to their history of Viking invasions, superstition, and ancient pagan rituals. The origins of Hogmanay have been traced back to pagan winter solstice rituals.

The Roman celebration of Saturnalia and Viking celebrations of Yule were mixed in to Scottish festivities around the New Year. During the Middle Ages, the pre-existing festivals were overshadowed by the feasts surrounding Christmas. The Reformation brought more changes, as the celebration of Christmas was discouraged and gift-giving and festivities associated with that holiday were moved to the New Year – creating the uniquely Scottish celebration of Hogmanay.

There are several traditions in New Year ceremonies surrounding fire . This comes from the pagan winter ceremonies when fire was a symbol of the sun returning. Fire was also believed to keep dark spirits away. In modern times, you can see fire in Hogmanay celebrations such as torchlight processions, bonfires, and fireworks.

A Viking longship burnt during Edinburgh’s annual Hogmanay (New Year) celebrations. (Lee Kindness/ CC BY SA 3.0 )

“First footing” is another interesting custom in Hogmanay. This is a belief claiming the first person to cross a home’s threshold after midnight on New Year’s Eve will determine the homeowner’s luck for the New Year. The ideal visitor? A dark-haired man bearing gifts such as whiskey, coal for the fire, small cakes, or a coin. The superstition dates back to 8th century when a blond visitor would be likened to a Viking – thus a bad omen.

Six More Unique New Year’s Traditions

There are of course many other customs and traditions associated with New Year’s. For example, a Spanish custom for good luck is to eat 12 grapes at the time the clock strikes midnight. One grape is supposed to be eaten at each stroke.

The Japanese hold “forget-the-year parties” to prepare for a new year and forget the past problems and concerns. New Year’s parties in the Netherlands, on the other hand, involve burning Christmas tree bonfires on the street and launching fireworks.

On New Year’s the Greeks serve a traditional cake called Vassilopitta with a coin hidden inside it. The person who gets the coin will supposedly have good luck in the following year. An almond hidden inside rice pudding serves a similar purpose in Sweden and Norway.

Example of vasilopita New Year’s cakes from 2010. (Vassilis/ CC BY SA 2.0 )

Gongs in Buddhist temples around the world are struck 108 times on New Year’s Eve, with each gong intended to expel a type of human weakness.

Top image: New Year’s fireworks over a golden temple. Source: CC0

Updated on December 31, 2020.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

January 1st, 2021

January 1st, 2021  Awake Goy

Awake Goy  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: