Earlier this month, Herzliya-based Otonomo announced that it would be going public. To get listed on Nasdaq, the company, which makes a cloud-based platform that allows car companies, service providers and apps to share and integrate data generated by vehicles, would normally need to go through a long, complicated process, opening its books to prospective investors and regulators and meeting minimum revenue and asset requirements.

But Otonomo won’t need to do all that. Instead, it will merge with a company called Software Acquisition Group Inc. II, which conveniently is already listed on Nasdaq, allowing it to quickly enter the stock exchange at an implied value of $1.4 billion.

Other Israeli firms are also entering the market via mergers with what are called special purpose acquisition companies or SPACs (pronounced “spacks”), mirroring a similar frenzy in the US, where SPACs have quickly become the go-to way to enter the market.

Israeli smart-car firm Innoviz Technology, a maker of sensors for self-driving cars, announced in December that it will become publicly listed on Nasdaq through a merger with a SPAC. Content recommendation firm Taboola in January said it expects to go public in the second quarter of 2021 by merging with a SPAC at a valuation of $2.6 billion; and on February 3, Calcalist reported that fintech firm Payoneer will go public on Nasdaq at a $3.3 billion valuation – also via a SPAC.

For smaller firms that want to raise money by going public, being acquired by a SPAC and undergoing a reverse merger is an increasingly popular avenue, allowing them to move more quickly than with a traditional IPO. Investing in SPACs themselves has also become a hot new financial instrument, though experts warn that doing so carries various risks, especially with so many SPACs frantically hunting for a limited pool of acquisition targets.

In August, the Financial Times dubbed the SPAC as perhaps the hottest asset class in 2020, noting that high-profile SPAC sponsors had helped the structure shed its image as a possible vehicle for fraud.

An illustrative image of the Wall Street sign with American flag in the Financial District of Lower Manhattan (Damien VERRIER; iStock by Getty Images)

SPAC listings in the US last year “went through the roof,” said David Fruchtman, a partner at the Tel Aviv-based Meitar law firm, which has accompanied client companies in merger and acquisition transactions and initial public offerings in Israel and abroad, and now in merging with SPACs as well. The firm handled the Innoviz merger with a SPAC.

In Israel the trend “is starting,” Fruchtman said. “There is definitely a significant increase both in interest in SPAC transactions as well as in actual companies pursuing it. It has become a very popular route to liquidity,” he said, adding that his firm is currently handling a few such deals that “hopefully will become public over the next few months.”

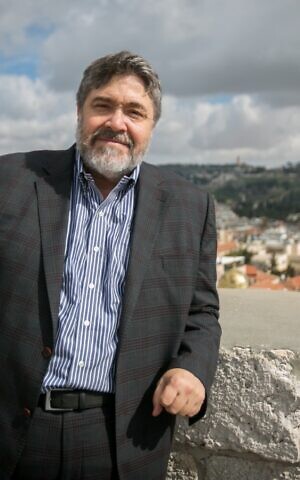

David Fruchtman, a partner at Tel Aviv-based Meitar law firm (Tomer Jacobson)

It will be “SPACs all the way” for 2021 as well, he said. “The numbers are dazzling,” and today it is “all that everyone is talking about.”

According to the data compiled by Nasdaq and SpacAlpha, in January 2021 US-listed SPACs accounted for 79 percent of all initial public offerings there. In 2020, they accounted for 53% the previous year, 23%.

In 2013, SPACs accounted for just 3% of the total IPO volume, according to the Nasdaq website.

In 2021 thus far there have been 160 SPAC initial public offerings, which have raised over $48 billion, according to data from SPAC Insider — over half the total of 248 in all of 2020. The average deal size this year was $302.1 million, according to the research firm.

That compares with 56 traditional initial public offerings with a minimum market capitalization of $50 million, which have raised $21.7 billion so far this year, according to IPO research firm Renaissance Capital.

From sideshow to a main event

So what are SPACs? Also called “blank check” companies, they are a form of a shell company set up by an entrepreneur, called a sponsor, for the specific purpose of raising money through an initial public offering of shares to then acquire or merge with another company – this one with operations — which is looking to go public via a reverse merger.

Once the SPAC goes public it has two years to find a target to acquire. If it doesn’t, then the money is returned pro rata to investors and the SPAC is liquidated. But if it does make a deal, those who invested in the SPAC will get a chunk of the company that’s been acquired, and potentially take home a neat profit.

Shares of the SPAC generally start out trading at $10, and the money raised from investors before and during the IPO is placed in an interest-bearing trust account, and cannot be used for anything else except to complete an acquisition or a merger with another firm.

When setting up the SPAC, the sponsors may have an idea of whom they want to merge with. Still, they don’t have to identify the target, to avoid having extensive disclosures during the IPO process, in which money is raised from investors which can be both known private equity funds or the general public.

Unlike traditional companies pursuing an IPO, SPACs are allowed to issue forward-looking earnings projections, allowing them to sell investors on a company that may not be profitable yet.

An illustrative image of a stock market ticker (AUDINDesign; iStock by Getty Images)

Before the merger is complete, the SPAC provides its investors with the opportunity to redeem their shares rather than become a shareholder of the combined company. The SPAC sponsor typically gets a 20% stake in the merged company both in shares and warranties.

SPACs have been around for decades, but they were generally associated with being a way for shady financiers to bring to market dodgy business ventures while avoiding public scrutiny.

Several such firms were set up before the 2008 financial crisis, but most of them flopped because of poor acquisition transactions and management, according to a Financial Times report looking into the structures. Akazoo, a Greek music streaming firm, was accused of massive accounting fraud, and the investors who backed the SPAC it merged with lost their entire investment, according to the FT.

OurCrowd CEO and founder Jon Medved in Jerusalem (Courtesy)

In recent years, however SPACs have attracted big-name underwriters such as Goldman Sachs, Credit Suisse, and Deutsche Bank. High-profile recent SPAC deals include that of Richard Branson’s Virgin Galactic, which merged with venture capitalist Chamath Palihapitiya’s SPAC in 2019. In 2020, Bill Ackman, a hedge fund billionaire, sponsored his own SPAC, and raised $4 billion in July. Sports betting site DraftKings Inc and electric truck startup Nikola both merged with a SPAC last year. DraftKings has a market valuation of some $24 billion on the Nasdaq today, while Nikola has a market capitalization of $8.4 billion, also on the Nasdaq.

In the US, “there are almost 300 SPACS waiting to find a company and they have raised almost $90 billion in 2020, a sixfold increase over 2019,” said Jon Medved, the CEO of the Jerusalem-based VC firm OurCrowd, in an email interview with The Times of Israel. “This has become a huge part of the public market. Where before it was a small sideshow, now it is one of the main events.”

Sabra SPACs?

The Tel Aviv Stock exchange does not currently allow SPACs, but it is involved in talks with the Israel Securities Authority about possibly allowing SPACs to be set up here as well, explained Tsofnat Mazar Laist, general counsel of the corporate finance department at the ISA, which is the capital markets regulator.

“In the US this instrument has become very popular recently– and as things that happen in the US, especially in the capital markets, tend to gradually come here too, we are now seeing demand for this fundraising vehicle,” she said in a phone interview.

In Israel SPACs don’t exist because TASE regulations, set up decades ago, say that companies can issue shares on the exchange only if they have an operational track record of a period of a year — SPACs, which are shell companies, don’t qualify — or if they raise over NIS 200 million ($62 million).

“Until now we have not seen this phenomenon on the Israeli market — mainly because there was a negative sentiment around these kinds of instruments, combined with the limitations” that exist, said Mazar Laist.

Tsofnat Mazar Laist, general counsel of the corporate finance department at the Israel Securities Authority (ISA) (Courtesy)

In a bid to ensure that only reputable sponsors set up SPACs in Israel, the ISA will probably only allow them to raise a minimum of NIS 300–NIS 500 million in the offerings, which will ensure that institutional investors, who are “better versed than others at making investment decisions,” will be part of the IPO process, she said.

Other requirements the ISA is examining are the approval of a general shareholder meeting for the merger transaction within a period of two to two and a half years, and that the entrepreneur (the sponsor) must invest at least 10% of the total amount the SPAC will raise, which they won’t be able to sell for a period of at least a year after the merger is completed.

“We are examining these days what terms should be in place so the instrument will be suitable to the Israeli market,” Mazar Laist said. “You can’t ignore that this instrument exists in the US, and you can’t ignore that there is demand for it here. But if we do it here, then we have to do it carefully, looking at the regulations abroad, and determine which balances are needed — terms which will enhance the correlation between the entrepreneur’s interest and that of the investor.”

SPAC to grow

Israel’s business environment, jam-packed with startups looking for cash infusions, seems especially ripe for SPACs, which are attractive to smaller firms that do not have the time or desire to go through the more arduous process of a straight IPO.

For years, Israeli tech firms in high growth stage seeking liquidity to finance their activities had three options: raise a large amount of funds via private investors; be acquired by a large firm, or seek an initial public offering of shares on the stock market – either locally or abroad.

An IPO process however is costly, long and full of regulatory hurdles, and is thus suitable mainly for larger firms that have reached certain revenue milestones. SPACs present smaller, fast-growing, companies with an option to get to public markets at an earlier stage, using a quicker and cheaper route.

“The reason that they have become so popular and that there are so many of them is because it is still more complicated to complete a successful IPO than it is to merge with a SPAC,” said OurCrowd’s Medved. “An IPO is an arduous and difficult process for even the most hardy of entrepreneurs.”

Otonomo’s CEO and founder Ben Volkow (Courtesy)

Ben Volkow, CEO and founder of Otonomo, said merging with a SPAC has allowed the firm to “move faster,” both in raising funds and in gaining the “advantages” of being a public company.

“To hold an IPO, I would have had to wait another two, three years” to meet the market requirements for a share sale, said Volkow in a phone interview, explaining that to hold an IPO on the Nasdaq an average of some $100 million in annual revenues are needed.

He could have raised the money from private investors and done an IPO in another two to three years with a higher valuation. But by moving sooner, he was able to build up his reputation with partners in the automotive industry – car-making giants like BMW, Mercedes Benz and Mitsubishi, he said.

“It helps them to know we are a traded company, and we are not going to disappear tomorrow and we won’t be acquired in the next two days,” he said. “I think these were our two main needs — the need for cash and to know that the future looks clear.”

Getting to the market takes some six to 10 months through an IPO process, versus potentially just a few months if the process is done via a merger with a SPAC, said Guy Preminger, partner and technology leader at PwC Israel in a phone interview.

During the months leading to the IPO, company officials work closely with regulators to finalize a prospectus with detailed financial information. Investment banks typically get a 7% or so chunk of the proceeds as an underwriting fee, and the last two weeks of the process, when the so-called roadshow is held, are crucial to the success of the share offering. The IPO process allows both regulators and investors to get a close look at the numbers. Questions are asked and answers are required, and this process brings to light any issues within the company that could become a problem in the future, with the aim of protecting the money of small investors who may invest in the firm after the IPO is held.

CyberArk staff and Nasdaq officials celebrate the company’s IPO in June 2014 (Photo credit: Courtesy)

A roadshow is when the underwriters of the offering and company executives pitch the firm, its story and management team to potential investors — institutional investors, analysts, fund managers and hedge funds — in a series of presentations at a variety of locations leading up to an IPO, in a bid to create a buzz around the company.

“The roadshow is critical,” Preminger said. “But it could be that exactly at that time something exogenic happens in the markets, not connected to the company but an external event, that could trigger a drop in the market. And because of the bad timing the planned initial public offering of shares could fail, and maybe you won’t get the price you are looking for. There may be no orders for the shares. So, you can freeze or postpone the IPO process,” but that creates a negative impression among investors, he said.

“There is no certainty regarding the success of an IPO,” said Preminger. With a SPAC merger, on the other hand, “theoretically, once a merger is agreed upon, the terms of what the valuation of the company will be and how much money is in the SPAC are all clear and set out in advance. With a SPAC you determine in advance all of the terms, and certainty is meant to be higher than in an IPO.”

The only uncertainty about the SPAC is whether the shareholders will approve the merger in the general shareholder meeting that is held a few months later, he said.

Both the traditional and SPAC routes to the market are “good and legitimate” ways to raise money, Preminger said. “It depends on the psychology of the company.”

Fruchtman, the attorney at Meitar, said that merging with a SPAC is “a more convenient method to go public, because the process is easier, it is faster, and the scrutiny is easier because you are merging with a company that is already listed. It is a more convenient method and less burdensome process which can lead to a quicker liquidity route for the company.”

“SPACs are definitely something to consider for companies that are in growth stage, and are considering how to raise liquidity,” he said. In the SPAC transaction, you don’t sell the company, which continues to operate. The controlling shareholder retains control, but also gets a “very viable route for liquidity.”

Investing blind

The biggest risks for those investing in SPACs are not knowing what company will be acquired, if any, and whether it is worth the price.

Investors are essentially blind, with no information beyond the reputation of the sponsor and the knowledge that they can redeem their funds if a merger deal never happens or falls through.

There are also concerns that SPACs may overpay for companies or merge with a dud as they near the two-year deadline and get desperate to find a mate.

Skyscrapers and NASDAQ building of Time Square on July 29, 2017 in New York, NY (lucky-photographer; iStock by Getty Images)

Because SPACs are not held to the same oversight or due diligence standards as traditional IPOs are, investors are not protected by the regulations surrounding a company going public and issues with the merging company’s books might not come to light.

And because the companies going public via a SPAC are generally smaller and less established than companies holding a traditional IPO, the risks to SPAC investors could be higher, and many could end up losing their money if the company and its management do not succeed.

There also could be a risk to the transaction as speculators and sophisticated investors, who may buy the SPAC’s shares, could torpedo the merger deal intentionally in the shareholders’ meeting, knowing they will be getting the dollars per unit ensured by SPAC regulations and making a profit from the process, said PwC’s Preminger.

Guy Preminger, partner and technology leader at PwC Israel (Eli Dasa)

“You want the company to be good, and you want there to be investors who won’t look immediately to exit the share as that could trigger a drop on share price. You want your investors to be there for the longer term,” he noted.

Once a company goes through a SPAC merger and is listed, it is required to file the same earnings reports and financial information as firms that went through a traditional IPO, so there is no extra risk in buying shares in such a company at that point other than the fact that it may be smaller and further from profitability.

“It is a share like all others; there is no difference between a SPAC share and an IPO share,” said Preminger. “In the medium or long run, the fact that they came to the market in two different ways doesn’t affect the performance of the shares.”

Learning to drive

For companies that can have one, a traditional IPO is still the gold standard, proof that they are a real player and not just an upstart.

“The biggest companies like Airbnb or DoorDash will continue to do IPOs. The biggest Israeli companies like Lemonade or Fiverr will also do IPOs,” said OurCrowd’s Medved. “SPACs will typically be smaller rounds than the big IPOs, but today’s SPACS are also not small. Typically, the average size for most SPACs is around $200 million, with the promoters of the SPAC looking to merge with a company at a value of several times that amount.”

While a SPAC opens doors to liquidity for younger, smaller firms, it also throws their management teams directly into the deep end of public trading without the swimming lessons that firms get when they go through a traditional IPO.

“A company must be really ready to be public because it needs to fulfill the disclosure, accounting, reporting, compliance and regulatory requirements that are part and parcel of being a public company,” said Medved. “Doing this right certainly takes a lot of management attention and skill. That is why many companies prefer to stay private. But, if you want to raise a big round and to use the public markets for what they are good at, then SPACs are a great new weapon in a VC’s arsenal or a company’s arsenal that needs to raise large amounts of capital and is ready to be public.”

Tal van Raalte, Foreign Securities Trader

Brokerage Department at Bank Hapoalim (Courtesy)

As opposed to a SPAC, the long IPO process “better prepares” entrepreneurs and the company’s management team for public trading, said Tal van Raalte, a foreign securities trader at the Brokerage Department at Bank Hapoalim Ltd.

“You are doing a lot of homework regarding what will be needed of you once you hold the initial public offering of shares,” he said.

“With a SPAC you are immediately a public company on the stock market, and that has its own risks, because, as you know, learning to drive in the passenger seat is not like actually driving. Moving from being a privately held company to a publicly traded company is a whole new world – everything you do needs to be made known to the public, and that is something you need to get used to. It is far easier to run a private company than a publicly traded one.”

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

February 23rd, 2021

February 23rd, 2021  Awake Goy

Awake Goy

Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: