MANTUA, Italy — The larger-than-life story of a 16th-century Jewish merchant is getting the comic book treatment in “The Wandering Jewess.”

Written by Gianluca Piredda and illustrated by Leo Sgarbi, the four-episode series is a graphic history of the adventurous life of Doña Gracia Nasi (1510–1569), a courageous woman who defied convention and fought for the religious freedom of herself and her fellow Jews in the shadow of the Spanish Inquisition.

Published in the last few weeks in the popular Italian weekly Lanciostory, the series follows Nasi, one of the wealthiest Jewish women of the Renaissance, who was forced to live in public as a Christian along with other hidden Sephardic Jews.

Piredda, a writer, journalist and screenwriter, has also found a loyal following in the American market thanks to his work on cult series such as “Airboy” and “Warrior Nun,” the latter of which has become a favorite among Netflix viewers.

Robin Wood, creator of Dago, on the right, with publisher Enzo Marino in 2015. (Courtesy)

The creators of “The Wandering Jewess” mixed reality and fantasy by bringing together Nasi and “Dago,” the fictional protagonist of a popular comic strip created in 1980 by South American writer Robin Wood. Dago made his debut in Laciostory in 1983, and his adventures are now produced in Italy.

Gianluca Piredda, author of ‘The Wandering Jewess.’ (Courtesy)

“He is a Renaissance character who has traveled the world, even arriving in the America of the Conquistadors, passing throughout Europe and Africa,” Piredda tells The Times of Israel. “He is a classic figure, typical of novels, who conquers and fascinates readers. Dago meets history and history meets Dago, as in the case of Gracia Nasi.”

Piredda says his goal in this series and others like it is to depict the lives of people who left an “indelible mark” on the 16th century.

“Gracia’s strength, tenacity and courage are personality traits that we’ve got to have in our magazine,” Piredda says. “In Ferrara, a city in northern Italy, she had the Bible translated into Spanish, helped the Jews to flee to Turkey, and she in turn was a fugitive, so much so that she became known as ‘the wandering Jewess’ — hence the title of our story. She is an influential personality, modern but little known to the public. It was worth telling.”

Her worthy tale

Nasi was born in 1510 to an established Spanish Jewish family who fled to Lisbon, Portugal, during the Spanish expulsion of 1492 so they could continue to practice their religion. Five years later, they were forced to convert to Christianity along with the rest of the Jews in Portugal.

At birth, Nasi was given the Christian name Beatrice De Luna, and although her family outwardly declared themselves to be Christian, she was raised in the Jewish tradition.

Gracia Nasi in Antwerp in a scene from ‘The Wandering Jewess,’ story by Gianluca Piredda and art by Leo Sgarbi. (Courtesy Piredda)

In 1528, at the age of 18, Nasi married Francisco Mendes, who was involved in the international spice trade in Lisbon. She soon realized she didn’t want to stay in Portugal and after her husband’s untimely death decided to move to Antwerp where her brother-in-law lived and managed the family business.

Nasi was helped by a large community of Sephardic Jews, who also supported those who wanted to go to Turkey via Italy. Between 1542 and 1543 the situation for the Jews worsened in Antwerp. Gracia hastened to leave in late 1544 or early 1545, having taken possession of half of the substantial assets of the company following the death of her brother-in-law.

Nasi fled to Italy, living in Venice and Ferrara before ultimately moving on to Constantinople, capital of the Ottoman Empire. It was when she lived in Ferrara between 1549 and 1552 that Nasi financed the publication of the Ferrara Bible in Ladino, promoted the publication of texts for crypto-Jews, and helped to reeducate Jews who had been forcibly converted to Christianity.

Gracia Nasi on her way to Antwerp in a scene from ‘The Wandering Jewess,’ story by Gianluca Piredda and art by Leo Sgarbi. (Courtesy Piredda)

She then briefly moved to Venice before leaving for Turkey in 1553. At that time, the sultan was looking for people skilled in trade and economic activities, and so the Jews found safe haven in the Ottoman Empire.

In Constantinople the Jews put out a special welcome for Nasi, calling her “señora” in a show of respect. She became popular within the Jewish community, and her generosity helped feed the city’s poor.

Not pulp fiction

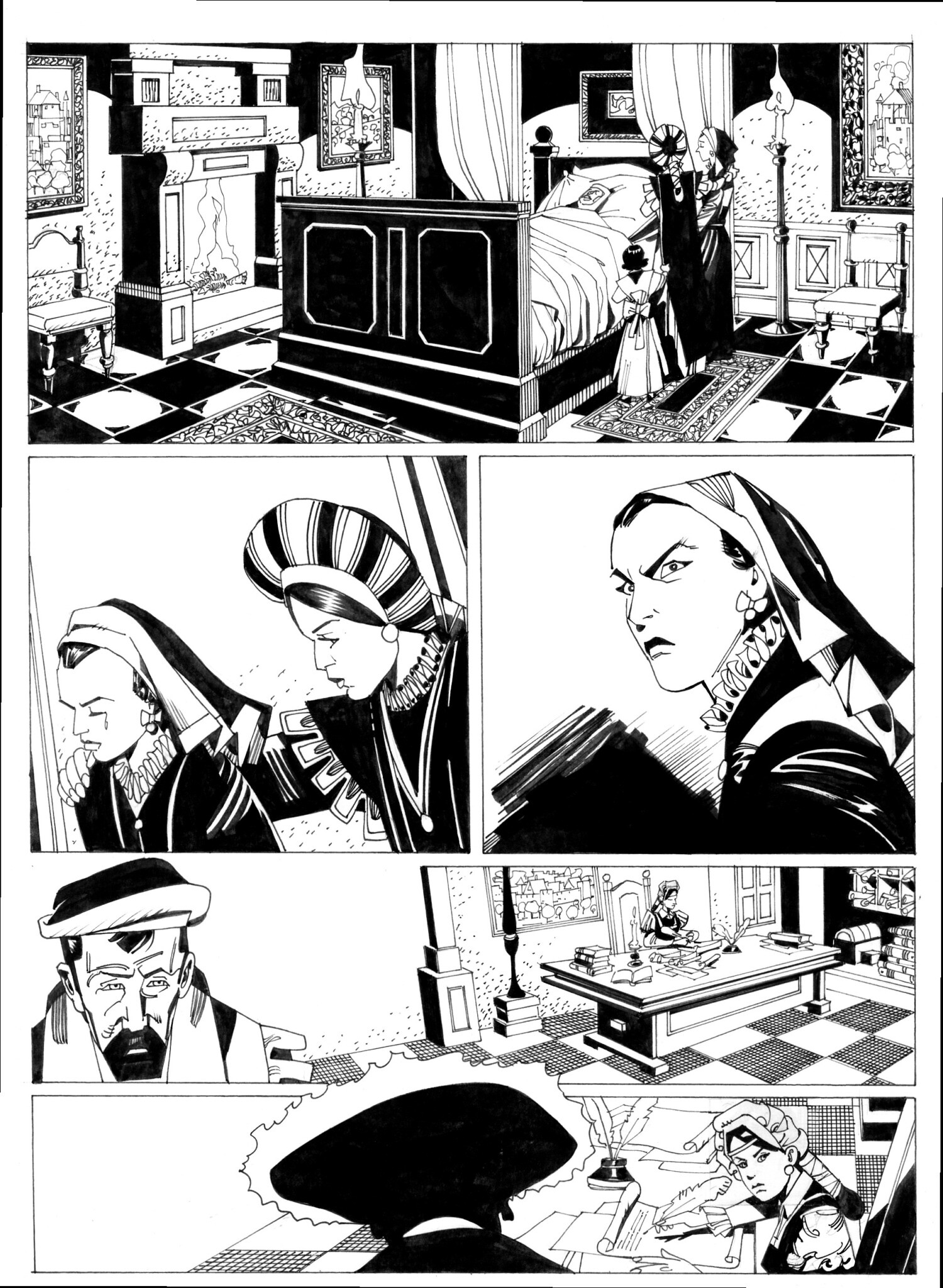

Gracia Nasi and her sister Brianda after the death of Brianda’s husband in ‘The Wandering Jewess,’ story by Gianluca Piredda and art by Leo Sgarbi. (Courtesy Piredda)

“The Wandering Jewess,” dedicated to Nasi, is based on real events. It is fictionalized and combined with fantastical elements, but nevertheless attempts to remains faithful to and respectful of Nasi’s legacy.

“We talk about her last stint in Italy, when she managed to leave from Venice for Turkey,” says Piredda.

“The story begins in Pesaro, a city in central Italy where Gracia ran a business. There, at that time, the city’s Sephardic synagogue was built. [Fictional character] Dago was contacted by Dr. Moise Hamon — a real person — the personal doctor of Sultan Suleiman and friend of Gracia Nasi. Hamon asked Dago for help in freeing Gracia, imprisoned in Venice,” says Piredda.

During her imprisonment, it was impossible to know what Gracia’s fate would be, but the wheels of diplomacy were turning.

“Through flashbacks we tell the story of the protagonist, her escape from the Iberian Peninsula, her arrival in Antwerp, the death of her brother-in-law, until her arrival in Italy,” Piredda says. “The Venetian cardinal Carafa appears making anti-Semitic speeches, and we see the mixed reaction of the people.

“Readers can relive the atmosphere of the time through various fictitious action scenes until Gracia’s arrival at the port from where she leaves for Turkey,” he says.

Dago in a scene from ‘The Wandering Jewess,’ story by Gianluca Piredda and art by Leo Sgarbi. (Courtesy Piredda)

Persecution and freedom are threads that follow Nasi throughout her lifetime.

“Gracia had to renounce her faith,” says Piredda. “But only superficially. Gracia Nasi grew up and lived secretly according to her own culture and principles. And this cost her a lot, having to flee from city to city.

“It’s precisely her ability to face adversity that fascinated me. Today we would say that she was a resilient woman, an example of feminism before its time, strong and courageous,” says Piredda.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

November 21st, 2020

November 21st, 2020  Awake Goy

Awake Goy  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: