Rakhi Dalal reviews translated short stories of Nabendu Ghosh, which not only bring to life history as cited in his Bangiya Sahitya Parishad Lifetime Achievement award but also highlights his ‘love for humanity‘

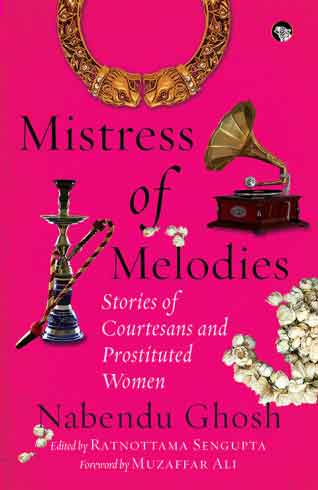

Title: Mistress of Melodies: Stories of Courtesans and Prostituted Women

Author: Nabendu Ghosh

Publisher: Speaking Tiger Books, 2020

Mistress of Melodies: Stories of Courtesans and Prostituted Women is acollection of six stories by Nabendu Ghosh in translation. It includes three translations by the editor Ratnottama Sengupta (Market Price, Dregs and Song of a Sarangi) and one each by Padmaja Punde (It Happened One Night) and Mitali Chakravarty (Anchor). The titular story was originally written in English by the author for a screenplay.

In the editorial note, Ratnottama Sengupta reflects upon the origin of the word prostitute from Latin word “prostitus” and asserts that its interpretation as “to expose publicly” or as “thing that is standing” does not have the abusive association usually identified with it. She refers to Rudyard Kipling’s short story, ‘On the City Wall’, for the denigrating connotation that the phrase “oldest profession”, a euphemism for the word prostitute, acquired later.

Treated as courtesans, as connoisseurs of arts, the women engaged in this oldest profession enjoyed high social standing in Mughal and Pre-Mughal era. Immensely trained in the fields of classical singing and dancing, their mannerism set a hallmark of etiquettes in society. It was only with the arrival of British that their institution gradually collapsed. The Sepoy Mutiny of 1857 rang the death knell for courtesans’ art. With their wealth seized and places plundered, they were punished for their involvement in the rebellion. The coming of British crown further brought Victorian ideas of morality and women chastity, thereby pushing the courtesans to the lowest rungs of society.

‘Song of a Sarangi’, set in nineteenth century Calcutta some years subsequent to Sepoy Mutiny, effectively brings forth the world of ‘baijis’ (courtesans) who had set up their kothas (business cum residence) in some neighbourhoods and enjoyed patronage of rich seths and babus of the city. Theirs was a world brought to life every evening with thumris sung and dances performed on the thaap of tabla tuned to harmonium and sarangi. Though their art was appreciated during the times, their sustenance in society hanged by the delicate threads tugged in the hands of their patrons. Nabendu Ghosh, through the character of Hasina Bai of Chitpore, places to the forefront the struggle and subsequent misery of a mother after she auctions her adolescent daughter to the highest bidder and plunges straight into a nightmare which upturns her life.

The story ‘Market Price’ illustrates the misery of a young widow Chhaya, who is allured into a fake marriage and betrayed after she willingly gives away her fortune to the man she trusts. Her story against the backdrop of city of Kashi also symbolically represents the ordeal of being a widow in the society. In the story ‘It Happened One Night’, we witness Tagar, a woman forced into the profession, trying to make as much money as she can till she isn’t worn out. For, she cannot end up like ailing Radha who pushes herself to the edge of death to earn little that she could to feed herself. Through this story, the author also focuses on the issue of sleep deprivation and illness, which is a price the women engaged in prostitution pay for their living.

‘Dregs’, written in first person narrative, while chronicling the life of Basana who enters the profession due to hardships that she faced, also very convincingly portrays the detestation which women engaged in prostitution are subjected to in a social system. Set in the 1940s in Calcutta, the story navigates the life cycle of brave Basana who succumbs to the destitution she confronts when her paramour abandons her after she becomes a mother. On the other hand, it also takes the reader through the mind of narrator, revealing his revulsion for Basana which is not only due to her profession but also a result of his own sense of deprivation, originating from his poor circumstances. He desires her but cannot have her so he is repulsed by her presence. It is only towards the end when she appears wretched, that he feels pity for her. This conflict, as experienced by the narrator, is rendered with such subtlety that it allows for an effortless transition of the distinct emotions, leaving the reader spellbound by the sheer brilliance of author’s skill.

In the story ‘Anchor’, Fatima resorts to the profession in order to provide for her son but cannot bring herself to give in to a stranger. Her defiance springs from her strong sense of self respect which she guides with all her might after her husband’s death. Rustam, who comes to Fatima in desperation, lets her go when he notices her helplessness. Here in sketching his character, the author also brings to reader’s attention the sufferings endured by countless people in the aftermath of Bengal famine.

‘Mistress of Melodies’ is written on the life of famous Gauhar Jaan of Calcutta. The author wrote this in English as the first draft of a fuller screenplay. He was captivated by the larger than life persona of first Indian diva of Armenian origin, who was immortalised in the annals of history by being the first ever person to sing for a gramophone record in the country. A highly accomplished woman in the field of classical singing and dancing, Gauhar Jaan enjoyed a privileged life. The author writes about her celebrated life and about the love which left her aching, after the death of her beloved Nimai Sen, till the very end of her life.

These stories of courtesans, of those engaged in prostitution as well as of those pushed to the verge in a society, are not merely the stories of their struggles, sufferings or helplessness but are also accounts of their faith in love and in the inherent goodness of people. It is love which compels Hasina Bai to start life anew with Uday Moinuddin and make Tagar dream of a new life with Shashi, his pimp. It lets Rustam, a wanderer, to finally attempt new beginnings with Fatima, their common grief the anchor which brings them closer.

Remembering Nabendu Ghosh, on his birthday i.e. on 27 March in 2019, renowned writer of Bengali Literature, Shirshendu Mukhopadhyay said:

“I wish I had more Nabendu Ghosh novels back then, in 1940s, for he has written on almost every upheaval of that period: the Bengal Famine, the tram strike, the rationing of clothes, the Direct Action riots, rehabilitation of Partition victims… This was perhaps because he considered Literature to be a way of tackling all that is destructive in society, in life. He was writing out of love for humanity.”

And indeed the stories in this collection, emphatically proffer a testimony of his love for humanity. A love which compelled him to write about the women engaged in the ‘oldest profession’. He wrote to address the many woes that afflicted not only forlorn prostituted women but also well-off Courtesans. With his stories, he portrays the predicament of women dragged into the clutches of prostitution and also paints a world throbbing to the surs of ragas and taals of Kathak whose custodians were also the upholders of culture and its mores in the times bygone. Through these stories perhaps, their legacies and their contribution to culture will be remembered for times to come.

Nabendu Ghosh (1917-2007) was a dancer, novelist, short-story writer, film director, actor and screenwriter. His oeuvre of work includes thirty novels and fifteen collections of short stories, including That Bird Called Happiness: Stories, edited by Ratnottama Sengupta (Speaking Tiger, 2018). As scriptwriter, he penned cinematic classics such as Devdas, Bandini, Sujata, Parineeta, Majhli Didi and Abhimaan. And, as part of a team of iconic film directors and actors, he was instrumental in shaping an entire age of Indian cinema. He was the recipient of numerous literary and film awards, including the Bankim Puraskar, the Bibhuti Bhushan Sahitya Arghya, the Filmfare Best Screenplay Award and the National Film Award for Best First Film of a Director.

Ratnottama Sengupta, formerly Arts Editor of The Times of India, teaches mass communication and film appreciation, curates film festivals and art exhibitions, and write books. Daughter of Nabendu Ghosh, she has written Krishna’s Cosmos, a biography of the pioneering printmaker Krishna Reddy, and also entries on Hindi films for the Encyclopaedia Britannica. She has been a member of CBFC, served on the National Film Awards jury and has herself won a National Award. In 2017, she directed And They Made Classics, a documentary about Nabendu Ghosh. She has recently edited That Bird Called Happiness (2018/ Speaking Tiger), Me And I (2017/ Hachette India), Kadam Kadam (2016/ Bhashalipi), Chuninda Kahaniyaan: Nabendu Ghosh (2009/ Roshnai Prakashan).

Rakhi Dalal is an educator by profession. When not working, she can usually be found reading books or writing about reading them. She writes at https://rakhidalal.blogspot.com/ . She lives with her husband and a teenage son, who being sports lovers themselves are yet, after all these years, left surprised each time a book finds its way to their home.

Originally published in Borderless Journal

IF YOU LIKED THE ARTICLE SUPPORT PEOPLE’S JOURNALISM

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

January 13th, 2021

January 13th, 2021  Awake Goy

Awake Goy  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: