I learned of Wiesel’s death through Facebook, and immediately went searching in my old file drawer for a photograph. The photo shows my face, very young and fresh, between the faces of Elie Wiesel and Oprah. I had written an essay for a contest in which we were asked to apply the story of Night to a contemporary concern. My piece, 815 Words About a Crime, was about my own complicity in violence committed worldwide as I sat consuming luxuries in the US, and I worked hard to self-implicate. I receive $10,000 for the essay from Oprah and a co-sponsor– AT&T, I think. The money was for books, so I bought everything I could read on the occupation of Palestine.

The photograph is one I have returned to again and again because the more I learned about the author of Night, the more I found myself searching his face, his eyes, for some signal that would explain how such a gentle, assured character with a such a pleasant handshake could so vehemently support the massacre of my Palestinian neighbors and friends. The photograph is comical to me, partly because of the aggressive way Oprah is pulling my arm, partly because there was a makeup artist who spent time “whitening” my face before the shot, partly because I remember being told I was not allowed to ask my question of Elie Wiesel, which was of course about Palestine, and mostly because I still see no trace of the mans’ politics in his eyes — and also no trace of my own politics in my eyes.

On the day of Elie Wiesel’s death, I learned two lessons that makes the photograph more significant to me now.

Lesson 1: Memory is for the Future

I did not know that Elie Wiesel was responsible for codifying the one-to-one association of the word “holocaust” with the massacre of 11 million European “others,” 6 million of whom were Jews. Nor did I know that in reading his influential text, Night, in high school, I was part of that codification. I remember starting conversations with friends in college that went, “Remember the Holocaust?” as a basis for whatever argument came next. We shared a collective memory borrowed and embedded in our souls from the work of Weisel, and later Taussig, Hatley, Derrida, Camus, and Bakhtin, all of whom argued in one way or another that to forget is a crime.

So I remembered, conventionally, and without much attention to the memories that were made un-collective by their absence in my high school curriculum.

Weisel made my classmates and me into third-party witnesses. As young students, we are always third party witnesses to our teacher’s stories, the novels we read, etc. We were good at it. The great classics are exactly that — classic because they formulate a canon of collective memories. After reading The Grapes of Wrath, I was able to say I “remembered” the Great Depression. After reading Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee, I could say, “Remember Wounded Knee?” as a point of fact or common ground upon which my co-conversationalist and I might agree, using that memory to measure whatever thing we might be discussing.

So it did not surprise me as much as catch me off guard that the synonymy of Holocaust with Nazi mass murder (of Jews especially) was being shaped passively by an author with whom I identified personally. My memory was a newer-than-I-thought political activity. The lesson was this: big things are glacial, and collective memories are formed passively, through the subtlety of people who do not coin so much as codify words that index “memories.” The main obligation of authors writing about violence is to create in the reader a third-party witness.

Learning that Elie Wiesel had generated the synonymy between “holocaust” and the Holocaust caught my attention because I realized that a third party witness (bearer of collective memory) is a kind of witness I have failed to think about carefully as an important witness type, among the others I have been imagining. I have thought carefully about James Hatley’s articulation of witness, which in the case of the Holocaust, is a witness-survivor. Because of the centrifuge of collective association and memory with the Holocaust, the word witness is often assumed to mean this type, a witness-survivor, whose existence or testimony itself, is a kind of justice. But there are other kinds.

My friend Ross is a witness of the massacres in Fallujah in 2004 and 2008 because he is a perpetrator, not a survivor. When he gives testimony, people approach him as a witness-survivor: it is the dominant model of a witness. In fact his testimony and actions carry very different weight with very different obligations: as a perpetrator, Ross finds that testimony or existence is not enough. He owes reparations and retributive exchange with those he violated.

There are bystanders, too, who claim to arrive neutrally to scenes of mass violation. They are obliged to speak, but not on behalf of the victims or as victims. Their testimony is supposed to support and amplify the voices of those who cannot otherwise speak or who lack the platform to be heard when they do.

Witnessing is never simple, because witness-survivors, let alone the other kinds of witnesses, are never pure, never only victims, never innocent. For example, it is an uncomfortable topic to discuss the role of Jews who aided and abetted the processes of the Holocaust. What kind of witness do we call those people? In mulling over the kinds of witness one can play at different moments and for different reasons, I overlooked the most common kind of witness: the third party witness is a special kind because in a way it is much simpler than the complexities of first-hand complicity, engagement, and survivorship.

As a third party, a reader of Night, I am a witness because I am being told a story, and my job is simply to remember. The direct accusations a story might offer are third-hand, and no matter my political position or historical inheritances, memory is the most obvious tool for justice. If the witness-survivor is obliged to give testimony, the third-party witness must simply remember. But why? Presumably to recognize from the past iterations in the present, and to act.

Lesson 2: Actually Being a Third-Party Witness Means No Longer Being A Third-Party Witness

I did not know or care about Elie Wiesel, the man, when I absorbed his memories as my own in high school.

I was inspired to write about Palestine, seeing in his own testimony obvious parallels and lessons about acting upon the mandate of witnesses to insist: “never again.” I was young and did not realize that for all types of witnesses, there is the great risk of failing to see the wisdom of one’s own testimony. He taught me how incredibly contradictory people can be, and upon his death my Facebook friends, mostly Palestine liberation activists, spoke eloquently about his hypocrisy.

Around the day of his death, the city of Khalil (Hebron) was locked down completely. Power lines were destroyed in Gaza. Several Palestinian people were run over and killed by settlers. It was the two-year anniversary of Mohammed Abu Khdeir’s death, a child who had been forced to drink kerosene and was lit on fire by settlers. Images of barbed wire, open air prisons, checkpoints… they resemble the scenes described of the pre-holocaust architectures and social tensions in Europe.

One friend posted:

“Elie Wiesel was a Nobel Laureate and a holocaust survivor but he was also a hypocrite and a racist Zionist who supported settlement construction and the ethnic cleansing and oppression of the native Palestinians.”

And another posted:

“Elie Wiesel spoke about hatred except when it involved his own, personal commitments. he failed to live up to the vision he constructed in his personal career during his life … I wish he had been more moral and principled to denounce violence regardless if it is committed by Muslims, Christians and by Jews … he never denounced Israeli settler violence or spoke out in support of Palestinian rights the way he did for others.”

I agree with them both.

Elie Wiesel is not the first influential person to offer theoretical tools and cultural tropes helpful in articulating the cause for Palestinian liberation, only to deny their own writing and theoretical contributions to make an exception in the case of Israel. James Hatley and Emannuel Levinas, two of my favorite scholars of witnessing, facing, and the ethical obligations therein, fail their own ethical standards when it comes to Palestine. Levinas, when asked if Palestinians have “face” (his own term for approaching recognition of the other and human accountability) basically said, “No.”

So we have two contradictions: How can he be one of my favorite scholars? And how can he be such a hypocrite?

It is similar with Heideggar. His theories of time and temporality are foundational for my own thinking. But he was a horrible racist. Ghandi’s theories of nonviolent strategy are genius, but from what I have read in his biographies, he really was a total pervert. Great ideas usually come from flawed people, in part because the cost of great ideas and their articulation is the total abandonment of almost anything else. So, I can forgive Ghandi enough to quote him.

But the political betrayal of one’s own work is a layer of contradiction that captivates me in a more complex way. This is not about flawed people: this is about hypocrisy at its height. If I take seriously the whole body of Wiesel’s articulations, in books, quotes, interviews, and political gestures, then I have to see him as a man who advocated for the collective memory of his own people’s suffering, and utilized it strategically to dehumanize and justify the massacre of Palestinian people. I feel tricked, force-fed collective memories of the Holocaust at the expense of all other stories and memories. I want to reject his terms, his stories. I want to find a Big Lie in order to refuse the betrayal. Can I forgive him his contradictions enough to quote him at all?

On the other hand, perhaps I was wiser in my teenage years than I am now, to take his writing at face value, to let it escape its author, to leap from the page and hold me (and him) accountable to collective memory in its simplicity. Thanks to my ignorance and indifference to the man himself, and to my ignorance of the many memories made un-collective by neglect, it was still Elie Wiesel –maker of third party witnesses– who inspired me to write about Palestine.

His testimony is more powerful than he wanted it to be. Shouldn’t we use it?

Night: Cover art

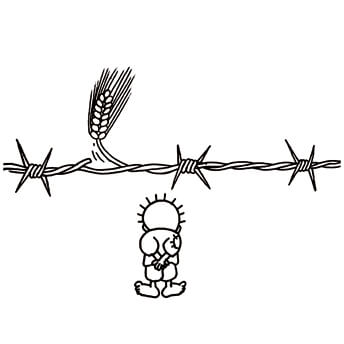

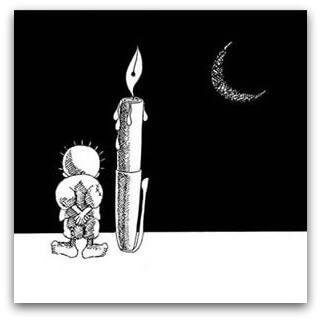

He left me with an image of a boy— a collective boy, not himself, not me, but a kind of icon for innocence and innocence lost. I took it up when I was about 15, and carried it as a memory. A few years later, when I saw the same boy on a t-shirt in Ramallah and learned about this character called “Handala,” I recognized the sameness of that boy, the same urgency for a third-party witness like myself to leap into action as a witness of other orders. The little boy orphaned during the Holocaust, his survival at all odds to escape and bear witness, is no different than the icon of Handala, a child, tattered, exhausted, looking ahead, through barbed wire at the night sky.

I am called by that boy to bear witness in person; to honor his death when his is lit on fire; to visit him in Ofer prison when is his plucked from his bed at night by Israeli soldiers and interrogated; to meet him in refugee camps in Syria, in Iraq, and Lebanon, in Jordan; to share his many names and many stories everywhere I can.

Handala ~ Naji Al-Ali

I was called by that boy, because I recognized him from a memory. I remember him as I was asked to do by Elie Wiesel himself. The purpose of remembering him is to make sure I recognize him in the present tense, not only as a past visage. Instead of being a third party witness, I am called by Handala to take ethical responsibility beyond simply remembering the past. I must struggle against my own complicity in his ongoing violation, to struggle against injustice as his ally. I become obliged to write new testimonies, to make new third party witnesses of all those read my words.

And if Elie Wiesel was unable to recognize the same boy, shame on him. Witnesses are faulty. They are most faulty when they are witness-perpetrators, when they, leaning on their victimhood, absolve themselves of responsibilities to others.

How can I embrace my many roles as witness-survivor, witness-perpetrator, third-party witness?

Handala ~ Naji Al-Ali

I try to stand with Handala in the night: on the same side of the fence, on the opposite side of the fence, as maker of the fence, as destroyer of the fence… no matter how the barbed wire pricks me, makes me bleed, I am never absolved of accountability to Handala. I am not accountable to his author, or to his illustrator. I am accountable to Handala himself, the collective figure that I remember, recognize, and conjure.

We are given the stories we are given. I was given the Holocaust first, the Nakba second. It is the way Palestine came to me, it is how Handala and I were introduced. Elie Wiesel cannot stop that. I cannot change that. Witnesses cannot escape their roles, their leaky, complex positions.

Because of this, I think I will continue to quote Wiesel, in part because I know he contradicts himself and I hope to hold him accountable even in death. It is my duty to recognize and act upon the memories that prepare me for the present, even if the arbiters of those memories are unwilling.

“To forget is a crime,” he insisted. So I remember. And so we much act.

Source Article from http://mondoweiss.net/2016/07/remembering-inspired-palestine/

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

July 6th, 2016

July 6th, 2016  Awake Goy

Awake Goy  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: