Saint Januarius is a saint venerated in the Roman Catholic Church . He is the patron saint of Naples but is best-known for a miracle that happens several times each year – the liquefaction of what is alleged to be the saint’s blood. According to popular belief, the liquefaction of the blood of Saint Januarius meant that all will be well, whereas its failure to do so was a signal that a disaster would soon occur.

Saint Januarius: A Life Recorded Mostly After His Death

The name Januarius is derived from the Latin ‘Ianuarius’, which means “consecrated to the god Janus.” This name was popular during Roman times and was given to children born in the month of January, which was sacred to the god. Little is known for certain about Saint Januarius (known also as San Gennaro). And most of the records about the saint’s life were written several centuries after his death.

One of the earliest references to Saint Januarius is a portrait of the saint, found in the 5 th century AD catacombs of San Gennaro in Naples. In the image, the saint has Mount Vesuvius behind him, which may be interpreted as highlighting the saint’s role as the protector of the city. Similarities have been noted between the depiction of the saint and that of Mithras, who was supposed to have been the protector of Naples in pagan times . This has led to suggestions that there was some sort of religious syncretism between the Christian saint and the pagan deity.

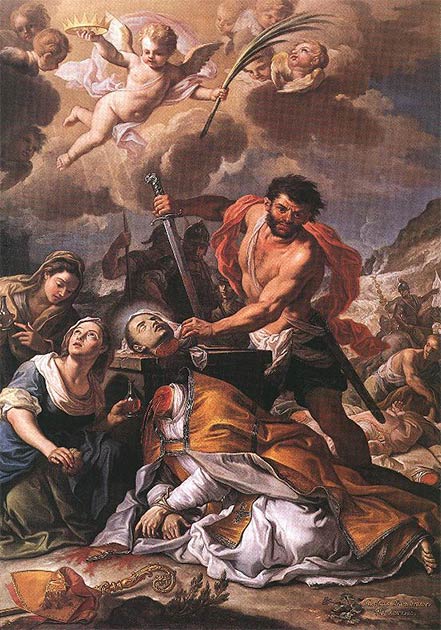

An early portrait of Saint Januarius. Note the two blood ampoules in the lower left corner. (Louis Finson / Public domain )

One of the written sources on Saint Januarius is the Martyrologium, written by the Venerable Bede during the 7 th / 8 th century. It is from this source that the Roman Martyrology derives its information about the saint. The entry for the 19 th of September (the feast day of Saint Januarius) is as follows:

“At Puzzoli, in Campania, the holy martyrs Januarius, bishop of Benevento, Festus, his deacon, and Desiderius, lector, together with Sosius, deacon of the church of Misenum, Proculus, deacon of Puzzoli, Eutychius and Acutius, who were bound and imprisoned and then beheaded during the reign of Diocletian. The body of St. Januarius was brought to Naples, and buried in the church with due honors, where even now the blood of the blessed martyr is kept in a vial, and when placed close to his head, is seen to become liquid and, bubble up as if it were just taken from his veins.”

It may be mentioned, however, that the miracle of the liquefaction of the saint’s blood was added to the Venerable Bede’s account at a much later date.

The Trials Of Saint Januarius And His Martyrdom

A more elaborate account of Saint Januarius’ martyrdom is found in the Breviary. In this version of the story, a certain “Timotheus, President of Campania,” is said to have ordered the execution of Saint Januarius and his companions. The saint was first thrown into a fiery furnace but was unaffected by the flames. He was then exposed to wild beasts in the amphitheater but was unharmed again.

The martyrdom of Saint Januarius as he is beheaded. (Girolamo Pesci / Public domain )

Finally, Timotheus decided to have the saint beheaded. Before the execution, however, Timotheus was struck blind, but Saint Januarius cured him. It is claimed that 5000 people were converted to Christianity after he cured the blind man. After the martyrdom of Saint Januarius and his companions, the cities of the coast sought to obtain their bodies for burial as they were considered to be holy relics .

In the case of Saint Januarius, his remains were taken from Pozzuoli, where he was martyred, to Benevento, where he had served as bishop. From there, they were brought to Monte Vergine, and finally to Naples. It is claimed that the saint performed many miracles for the city and its inhabitants, one of the most notable being stopping eruptions of Mount Vesuvius .

A Miracle: The Liquefaction Of The Blood Of Saint Januarius

More famous than all the miracles attributed to Saint Januarius, however, is the liquefaction of his blood, a miracle that occurs several times each year. According to tradition, after the martyrdom of the saint, some of his blood was collected by a pious Christian woman by the name of Eusebia. The blood shed by martyrs is also considered to be a type of relic and was therefore collected and kept for veneration.

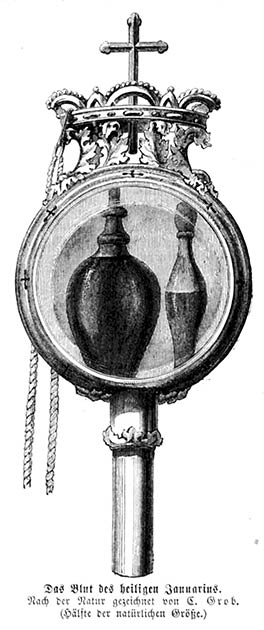

Drawing of the reliquary containing the two ampoules said to hold the blood of Saint Januarius. ( Public domain )

In the case of Saint Januarius, his blood was kept in two ampoules (small vials). Since the 17 th century, these two ampoules, which are hermetically sealed, have been kept in a silver reliquary, in between two round glass plates. One of the ampoules contains much less blood than the other, as Charles III, the king of Spain, is said to have sent some of the blood back to Spain during the 18 th century.

It is not entirely clear as to when the miracle of the liquefaction of Saint Januarius’ blood was first noticed. According to tradition, the saint’s blood liquefied for the first time when his remains were being moved by Saint Severus, the Bishop of Naples during the 4 th / 5 th century AD, from a place called Agro Marciano to Naples.

During the journey, the bishop came across a woman (perhaps Eusebia herself) with the two ampoules of Saint Januarius’ blood. The legend goes on to claim that in the presence of the saint’s remains, the blood liquefied. Tradition aside, the first recorded instance of the liquefaction of Saint Januarius’ blood is dated to the year 1389. That year, there was a huge procession to witness the miracle. Needless to say, the faithful continued to flock to Naples to see for themselves the liquefaction of the saint’s blood in the centuries that followed.

The reliquary containing the ampoules of the saint’s blood is normally kept in a safe behind the altar of the Chapel of the Treasure of Saint Januarius. There is an interesting story behind the foundation of this chapel. According to the story, between 1526 and 1527, the city of Naples was suffering greatly as a result of the war between the French and Spanish (the Italian Wars), a plague, and the eruption of Mount Vesuvius. The people of Naples were desperate and turned to Saint Januarius for help. The representatives of the city made a solemn vow to Saint Januarius, and a contract was “signed” between the saint and five Neapolitan notaries. In exchange for the saint’s protection and deliverance from the calamities they were facing, the people of Naples promised to construct a new chapel in the cathedral in honor of the saint. It seems that Saint Januarius provided his aid to Naples, and in return the chapel was built to honor him for his great deeds.

Michele Dato’s Necklace of St. Januarius, as displayed in the Museum of the Treasure of San Gennaro, Naples, Italy. (Wantay / CC BY-SA 4.0 )

The Chapel Of The Treasure Of Saint Januarius

Although the blood of Saint Januarius is arguably the chapel’s most prized possession, it is not its only treasure. At the altar, for instance, there is a bust of the saint made of precious metals, within which is the skull of Saint Januarius. Other treasures were donations made by various individuals to the chapel. One of these, for example, is the Necklace of Saint Januarius, which was made in 1679. The original necklace was made by Michele Dato, a Neapolitan goldsmith, and consisted of 13 gold links with diamonds, emeralds, and rubies that were donated by the chapel’s deputation committee for the saint’s reliquary bust.

In the centuries that followed, kings and queens who reigned in Naples, or visited the city, made their own contributions to the necklace, and as a result, more precious stones were added to it.

Interestingly, there is a pair of earrings in the upper part of the necklace. These were not donated by a royal figure, but by an unnamed commoner. The woman, as gratitude for surviving the plague, donated the most precious object she had, the earrings handed down from her grandmother, to the chapel. The deputation committee recognized this noble gesture and set the earrings in a place of honor. The last addition to the necklace was made in 1929, by Marie-José of Belgium, the wife of Umberto II, the last king of Italy. When the future queen visited the chapel, she did not bring with her any precious stones as a donation. Embarrassed, Marie-José took the diamond ring she was wearing and gave it to the chapel. The ring was placed in the center of the necklace, near the commoner’s earrings.

The San Gennaro procession in Naples in 1631, dedicated to the Patron Saint of Naples, Saint Januarius. (Micco Spadaro / Public domain )

How And When The Blood Liquefaction Event Takes Place

The liquefaction of Saint Januarius’ blood is supposed to take place (at least) three times each year, on the 19 th of September (the saint’s feast day), the 16 th of December, and the Saturday before the first Sunday of May. During these times, the relic is brought out, and exposed to the public. Sometimes, the liquefaction takes place almost immediately, whilst at other times, it may take several hours, or even days. It has also been recorded that on some occasions, the blood did not even liquefy, which was taken as a bad omen. For example, the blood of Saint Januarius did not liquefy in 1939, the year when World War II broke out, and in 1980, when southern Italy was struck by the Irpinia earthquake.

Therefore, there is great celebration amongst the crowd when the blood does liquefy. It may be added that the blood of Saint Januarius may liquefy outside these three dates. For instance, when Pope Francis visited Naples Cathedral on the 21 st of March 2015, the saint’s blood liquefied. The last time that the saint’s blood is recorded to have liquefied before a pope was in 1848, during the papacy of Pope Pius IX.

The imposing statue of Saint Januarius behind the altar at The Chapel of the Treasure of San Gennaro in the Cathedral of Naples, Italy. Source: Antonio Nardelli / Adobe Stock

Scientists Question The Blood Miracle With Chemistry

Although the liquefaction of the blood of Saint Januarius is commonly accepted to be a miracle, it is certainly not without its sceptics. Unlike believers, who view the liquefaction of the blood as the result of prayer and the saint’s intervention, these sceptics propose scientific explanations. One of these, for example, is that the blood is in fact a substance that liquefies in the presence of a source of heat. An example of such a substance that resembles blood is a mixture of a small amount of beeswax in olive oil that is colored with a red pigment.

Believers, however, argue that, based on records kept for more than a century, the liquefaction of the blood may take place at various temperatures. Moreover, it has been pointed out that there is no direct relation between temperature and the time it takes for the blood to liquefy. In fact, as already mentioned, there have been occasions when the blood did not liquefy.

Another more recent hypothesis is that the blood is actually a thixotropic gel. This means that the contents of the ampoules will liquefy when disturbed, i.e. moved, stirred, or shaken. The researchers also published a recipe to make this gel, the materials of which were easily obtained during the 14 th century, when the liquefaction of the blood was first recorded.

One objection to this is the fact that the blood does not always liquefy. Another is that this type of thixotropic gel has a shelf-life, i.e. that it loses its thixotropic properties after two years. Nevertheless, it has been noted that some gels may last a decade, and its shelf-life is dependent on certain factors, including the way it was sealed, and the concentration of the ingredients.

The two hypotheses propose that the ampoules do not contain any blood, but a chemical substance. Perhaps the only way to find out for sure, and to settle the matter, is to scientifically analyze the contents of the ampoules. The Church, however, has so far refused to allow such analyses to be performed.

One argument put forward by the Church is that such analyses may cause damage to the ampoules and the blood. Another reason is perhaps the popular resistance that the Church may face should it allow such analyses to be performed.

During the Second Vatican Council, it was decided that several saints, including Saint Januarius, should be removed from the liturgical calendar. The popular resistance faced by the Church was so strong that it abandoned this decision. Thus, it was decided that whilst the liquefaction of the blood of Saint Januarius may not be considered a miracle by the Church, it is an event that cannot be explained, and it is believed to be a miracle by the faithful.

Top image: Left: St Januarius’ blood being examined in Naples. Credit: The Catholic Herald . Right: An early portrait of Saint Januarius. Note the two blood ampoules in the lower left corner. (Louis Finson / Public domain )

By Wu Mingren

References

Boston Catholic Journal, 2020. Roman Martyrology. [Online]

Available at: http://www.boston-catholic-journal.com/roman-martyrology-complete-in-english-for-daily-reflection.htm

Moshinsky, B., 2016. A 627-year-old ‘blood miracle’ failed to occur, heralding disaster for 2017. [Online]

Available at: https://www.businessinsider.com/blood-of-san-gennaro-fails-to-liquefy-meaning-2017-could-be-a-disaster-2016-12

museosangennaro.it, 2020. Museo del Tesoro di San Gennaro. [Online]

Available at: https://museosangennaro.it/en/

Nickell, J., 2009. Science And The “Miraculous Blood”. [Online]

Available at: https://centerforinquiry.org/blog/science_and_the_miraculous_blood/

Saldanha, S., 2019. Blood Miracle of St Januarius-Gennaro An Ongoing Miracle of the Church. [Online]

Available at: https://medium.com/@suniljepc/blood-miracle-of-st-januarius-gennaro-an-ongoing-miracle-of-the-church-cc191a229310

Suplee, C., 1991. Scientists Replicate ‘Miracle’. [Online]

Available at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/1991/10/14/scientists-replicate-miracle/9a66d9f7-8ec5-4db8-b719-aee4d26868c1/

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica, 2010. Saint Januarius. [Online]

Available at: https://www.britannica.com/biography/Saint-Januarius

Thurson, H., 1910. St. Januarius. [Online]

Available at: https://www.newadvent.org/cathen/08295a.htm

www.italyheritage.com, 2020. San Gennaro (Saint Januarius). [Online]

Available at: https://www.italyheritage.com/traditions/calendar/september/19-san-gennaro.htm

www.visitnaples.eu, 2020. The blood of St. Gennaro: miracle or artful trick?. [Online]

Available at: https://www.visitnaples.eu/en/neapolitanity/discover-naples/the-blood-of-st.-gennaro-miracle-or-artful-trick

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

October 5th, 2020

October 5th, 2020  Awake Goy

Awake Goy  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: