Many myths have cropped up in the centuries since Columbus landed upon the shores of Hispaniola. While some of these myths have come to be seen for what they are, many more persist in the zeitgeist as fact. One such myth is that the Aztecs believed that Hernan Cortes, the leader of a band of conquistadors, was in fact a reincarnated deity by the name of Quetzalcoatl.

As the story goes, the Aztec believed in a white, bearded god named Quetzalcoatl, who, long ago, had disappeared into the east. Before he left, however, he promised to return. When Cortes and his crew of Spaniards came ashore in Mexico in 1519, many thought they were gods.

And when their march inland took them to the Aztec emperor’s doorstep, he recognized who Cortes truly was. A pious man, Montezuma proclaimed Cortes was in fact Quetzalcoatl himself, come to fulfill the prophecy. He then graciously handed over the keys to his empire to the bearded, white god.

This tale has become so pervasive in the modern ethos that I even learned it in my 9th grade world history class. Told by our teacher that this story was historical fact, I went on believing the myth for years. It wasn’t until graduate school, when I became more interested in the history of the Atlantic World and the colonial societies it produced, that I learned that the story of a white bearded god named Quetzalcoatl was a myth.

In this article, I’d like to explore this myth, examining why it’s untrue, how it came about, and why both European and Indigenous people of post-Conquest Mexico came to believe in it. But first, let’s quickly delve into the history of the real Quetzalcoatl and his theological origins in Mesoamerica.

The Real Quetzalcoatl, the Plumed Serpent

The Plumed Serpent made his first appearance in the archaeological record over 2,000 years ago. In the heartland of the Olmec civilization, at a site known as La Venta in the present-day state of Tabasco, Mexico, archaeologists discovered a carving of a snake sporting a beak and feathered crest, with birds (or quetzal in Nahuatl, the language of the Aztecs ) on either side. Under the Olmecs, La Venta flourished from 900 BC to somewhere between 300 and 200 BC. Credited as the mother of civilization in Mesoamerica, the Olmec spread their culture throughout the region, including their belief in the Plumed Serpent deity.

A photo of La Venta Stela 19, the earliest known representation of the Feathered Serpent in Mesoamerica. ( Audrey and George Delange )

The next great civilization that left signs of worshiping Quetzalcoatl was Teotihuacan. While scholars do not know who built and inhabited this magnificent ancient city, its people etched their reverence for Quetzalcoatl into stone. The site contains three large pyramids: the Pyramid of the Sun, the Citadel, and the Temple of Feathered Serpent.

Built around 150 AD, the Temple of the Feathered Serpent, also known as the Temple of Quetzalcoatl, was the third largest pyramid in the city. Made up of seven tiers, the facade of the pyramid swarms with carvings of snakes. The symbolism of Quetzalcoatl here is intriguing.

Archaeologists have argued that the ornate headdresses found on the serpents represent time. This suggests the people of Teotihuacan gave Quetzalcoatl a role in the creation of the calendar, a role he would continue to play in later civilizations. Though Teotihuacan lay abandoned by 750 AD, it represents an important point in the evolution of Quetzalcoatl in Mesoamerican thought.

Quetzalcoatl head in Teotihuacan . ( Josue /Adobe Stock)

By the time the Aztecs emerged on the scene in fourteenth-century Mesoamerica, Quetzalcoatl had become an important god for many peoples of the region. And during the centuries of the Aztecs’ rise to power, the god came to play a variety of roles in Aztec belief .

For one, they credited him with the creation of the universe, humanity, the calendar, and their most important crop, corn. The Aztecs also drew upon long standing traditions that associated Quetzalcoatl with science, arts, and learning, as well as the planet Venus. And, as if this were not enough, he was also closely associated with rain.

Despite the various roles and deeds ascribed to Quetzalcoatl in Aztec theology, he was not the most important god worshipped in Tenochtitlan, the capital of the Aztec empire. Indeed, nowhere in the traditions of the Aztec, or the Olmec, Toltec, Maya, or numerous other cultures for that matter, did the Plumed Serpent god disappear, promising one day to return.

Quetzalcoatl. ( guillermo /Adobe Stock)

Lost in Translation

So how did this myth come about? As with most historical phenomena, many events fed into the Cortes-as-Quetzalcoatl legend, like tributaries into a river. Perhaps one of the first to occur, chronologically, was a simple matter of mistranslation.

When the Spanish arrived on the Mexican coast in 1519, they were a complete unknown in the Mesoamerican world. Thus, as the Spanish made their way inland, the towns they passed, and sometimes destroyed, had no idea what to call them.

In sixteenth-century Mesoamerica, part of a person’s identity was their city of origin or the social role they filled. Eventually, Nahuatl speakers denoted the Spaniards as Caxtilteca, or people of Castile; but that was years in the future. For now, no one knew from whence the Spanish had come, and so could not label them in traditional fashion.

It seems, however, that many people in the region were impressed with Spanish guns and horses. After all, nothing like this existed in Mexico at the time. When the Spanish recorded the interactions they had with the various peoples of central Mexico, they noted that these people called them ‘teotl.’ In Nahuatl, teotl can mean god, and this was the translation the Spaniards latched onto.

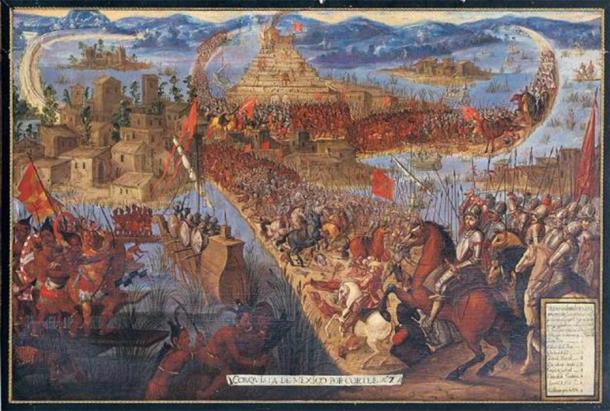

‘The Conquest of Tenochtitlán’ ( Public Domain )

But, teotl had other meanings as well. As historian Matthew Restall explains, “it could be combined with other words… to qualify them not as specifically godly or godlike, but as fine, fancy, large, powerful, and so on.”

Impressed by the horses and goods the Spanish brought with them, the people who met Cortes on his march inland surmised the Europeans were important people. And, lacking any other way to distinguish them in speech, used the word ‘teotl’ to denote this, which later Spanish chroniclers misinterpreted as ‘god.’

Not So Reverent Actions

If the Aztecs had truly believed that Cortes was a god, Cortes himself would certainly have made note of it. But in all the letters he wrote to King Charles V in which he attempted to establish political and moral legitimacy for the war he started, he never mentions it. Even when describing his first encounter with Montezuma, the Aztec emperor, Cortes portrays Montezuma as recognizing the Spaniard’s humanity. In a letter to Charles V, Cortes recounted how Montezuma told him, “See that I am of flesh and blood like you and all other men, and I am mortal and substantial.”

Whether or not Montezuma ever actually spoke those words, we can never know. But, if the Aztec emperor had proclaimed Cortes’s divinity, why did the conquistador leave it out of his letter? Surely, such a thing would have gone far in his attempts to justify the conquests he sought in the New World.

Additionally, in the midst of the battle for that conquest, the Aztec did not sit passively by and watch the Spanish take their capital of Tenochtitlan. While they found Spanish horses and guns rather fascinating, the Spaniards themselves had quickly worn out their welcome.

In traditional Aztec warfare, soldiers captured enemies for sacrifice, which was thought to be an honorable death. In their war against the conquistadors, however, Aztec warriors delivered a devastating blow to the back of their opponent’s head whenever they could. In pre-conquest Tenochtitlan, such a death had been reserved for the city’s criminals.

Through the re-examination of the word ‘teotl’ and closer look at the actions we know the Aztecs took in regards to the Spanish presence , we can say with certainty they did not view Cortes as a god. To get a better understanding of how this myth came to permeate both European and Mesoamerican histories of the conquest, we need to examine the works of prominent thinkers in post-conquest Mexico.

Planting the Seeds of a Myth

One of the most prominent of these thinkers is the Franciscan friar Toribio de Benavente, known to history as Motolinía. While in the decades following the Aztec-Spanish War, many Spanish chroniclers made mention of the variant forms of teotl used to identify the conquistadors, most left it at that. They simply observed its use, telling their readers it translated as ‘god’ or ‘gods’ and moved on. But Motolinía took it a step further.

He saw this mistranslation as evidence of God’s approval. Writing about the conquest and post-conquest era while living in the Valley of Mexico as a missionary, Motolinía noted that the Nahua people “called the Castilians teteuh, which is to say gods, and the Castilians, corrupting the word, said teules.” For Motolinía, the use of this word denoted that the Mesoamericans had been awaiting the Spanish arrival. As Restall notes, this “anticipation… proved the Conquest was part of God’s plan for the Americas.”

Some 30 years after Motolinía scribbled those words, the Cortes-as-Quetzalcoatl myth reached its penultimate form in the work of Bernardino de Sahagún. Known as the Florentine Codex , this gargantuan work comprised 12 books that took around 45 years to compile.

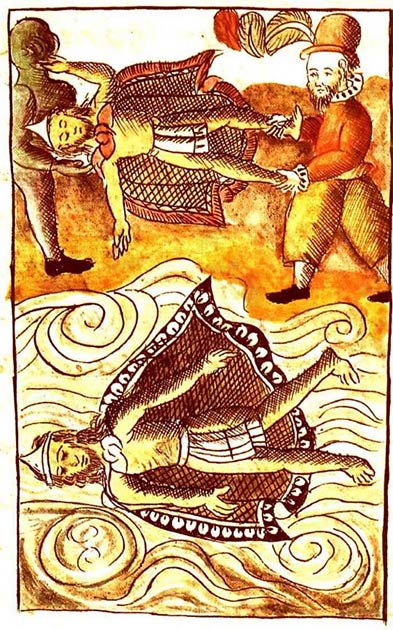

Spaniards disposing of the bodies of Moctezuma and Itzquauhtzin in the Florentine Codex. ( Public Domain )

An intelligent man with an aptitude for languages, Sahagún travelled to Mexico as part of the Franciscan order’s attempts to convert the Indigenous populations to Christianity. During his time there, Sahagún learned to speak Nahuatl.

With his newly earned Nahuatl skills, Sahagún recruited the children of Nahua elites to work with him on creating the Codex. With Sahagún essentially filling the role of project manager, his Nahua assistants wrote most of the Florentine Codex .

This gave the Codex a decidedly Indigenous point-of-view on the conquest of Mexico. Yet, in this text composed by young Aztec scholars in the decades following the conquest, we see the following depiction of Montezuma preparing for Cortes’s arrival:

“When Moteucçoma heard the news, he immediately sent people for the reception of Quetzalcoatl, because they thought it was him who was coming, because they were expecting him daily.”

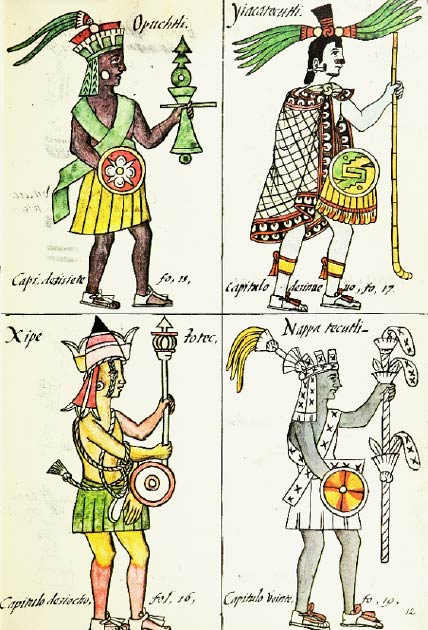

Aztec Gods in the Florentine Codex. (Gary Francisco Keller/ CC BY 3.0 )

Reasons for Believing

Even though the form of the Cortes-as-Quetzalcoatl myth so many of us were taught as children didn’t come about until the 1560s, some forty years following the fall of the Aztec empire, both European and Nahua populations had reason to buy into it.

By the time the Florentine Codex was published, the days of the conquistadors were long gone and Spain’s New World empire established. For some Europeans, the notion of Indigenous inferiority sufficed as an explanation for the success of the Spanish conquistadors. Other Spaniards who immigrated to the colony built on the ruins of the Aztec empire, known as New Spain, undoubtedly observed the unjust treatment the Indigenous populations faced at the hands of the Spanish empire.

Luckily, the Cortes-as-Quetzalcoatl myth helped to assuage, at least in part, whatever guilt colonists may have felt. As historian Camilla Townsend put it, the myth showed that “the Europeans had not only been welcomed, they had been worshipped.”

The Nahua had the opposite question to answer: How did we fall from power? The Nahua who helped Sahagún create the Florentine Codex knew the Indigenous populations of the New World were not inferior to the Europeans. After all, their ancestors had built the most sophisticated city in the world, Tenochtitlan, and the Aztec empire had never before known defeat. And on top of that, they had personal memories of fathers and grandfathers who had fought against Cortes and his conquistadors.

To account for the fall of the Aztec from power, the Nahua writers of the Florentine Codex ascribed a generally positive attribute, piety, to their ancestors, rather than the negative attribute used by some Europeans, inferiority. By explaining the Aztec loss through this positive lens, the Nahua of post-conquest Mexico could remain confident in their ancestor’s strength and intelligence, while also accounting for their defeat in the Aztec-Spanish War. Could Montezuma and his empire be blamed for losing if they had been stunned, even just temporarily, by overwhelming reverence to their gods?

Quetzalcoatl, the plumed serpent. ( Kazakova Maryia /Adobe Stock)

Exposing the Cortes-as-Quetzalcoatl Myth

The Cortes-as-Quetzalcoatl myth had been building steam for a few decades before work on the Florentine Codex began. By the 1560s, it had reached its final form, the one that survives to this day. In order to truly understand what happened in the years of the Spanish invasion and conquest of Mexico, indeed to understand the history of European colonization in general, we must expose this myth, and others like it, as falsehood.

Myths like this deny agency to the colonized, cause European victory to seem inevitable when it was not, and keep us from knowing the true, much more interesting story.

Top Image: Quetzalcoatl, detail. Source: Manzanedo/ Deviant Art

By Jordan Baker

References

Mark Cartwright, “Quetzalcoatl,” ancient.eu.

Mark Cartwright, “Olmec Civilization,” ancient.eu.

History.com Editors, “Teotihuacan,” history.com.

Alfredo López Austin, Leonardo López Luján, and Saburo Sugiyama, “The Temple of Quetzalcoatl at Teotihuacan: Its Possible Ideological Significance,” Ancient Mesoamerica , vol. 2 (1991): 93-105.

“Aztec Civilization,” newworldencyclopedia.org.

Wu Mingren, “Quetzalcoatl: From Feathered Serpent to Creator God,” ancient-origins.net.

Camilla Townsend, “Burying the White Gods: New Perspectives on the Conquest of Mexico,” historycooperative.org.

Matthew Restall, Seven Myths of the Spanish Conquest (New York: Oxford University Press, 2003), 112.

Hernan Cortes, translated and edited by Anthony Pagden, Letters from Mexico (New Haven: Yale Nota Bene), 86.

Townsend, “Burying the White Gods,” historycooperative.org.

Restall, Seven Myths of the Spanish Conquest , 113.

Humberto Ballesteros, “The Nahuas and Bernardino de Sahagún,” college.columbia.edu.

Bernardino de Sahagún, ed. James Lockhart, Historia de la Conquista de México (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993), 63.

Camilla Townsend, Fifth Sun: A New History of the Aztecs (New York: Oxford University Press, 2019), 95.

Townsend, Fifth Sun, 96.

Ibid.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

August 3rd, 2020

August 3rd, 2020  Awake Goy

Awake Goy  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: