Hermann Hendrich is one of those artists whose work has been used time and again to illustrate articles related to Germanic and Norse sagas all over the Internet, although up until now, I had not considered the idea of writing a piece about him. In spite of personally finding some of his paintings -from a strictly technical perspective- sketchy at best, I finally decided to dedicate an article to this German artist whose name seems to have been completely forgotten by the world at large, in spite of the apparent success that he achieved at the end of the 20th Century.

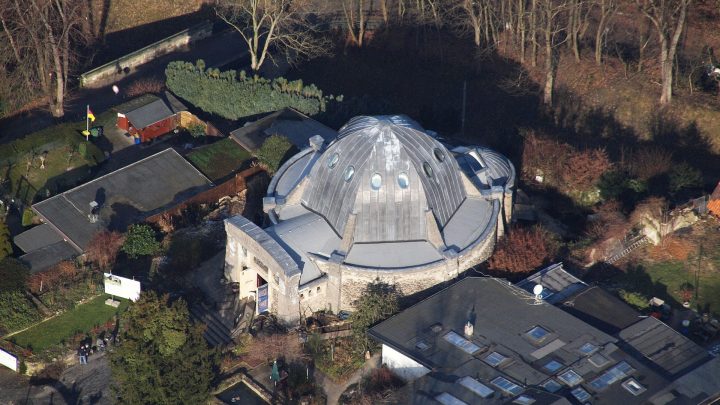

Said all this, what caught my attention most powerfully about Hendrich was obviously not his paintings, but the work he devised in collaboration with architect Bernhard Sehring. I think that is doubtlessly where his strongest legacy actually resides. I’m talking about the Nibelungenhalle Königswinters and Walpurgishalle Thale temples dedicated to the figure of Richard Wagner and the world of the Norse Sagas. Suffice to say it is precisely inside these magnificent late Art Nouveau buildings where Hendrich’s recently restored paintings are accessible to the public to be seen.

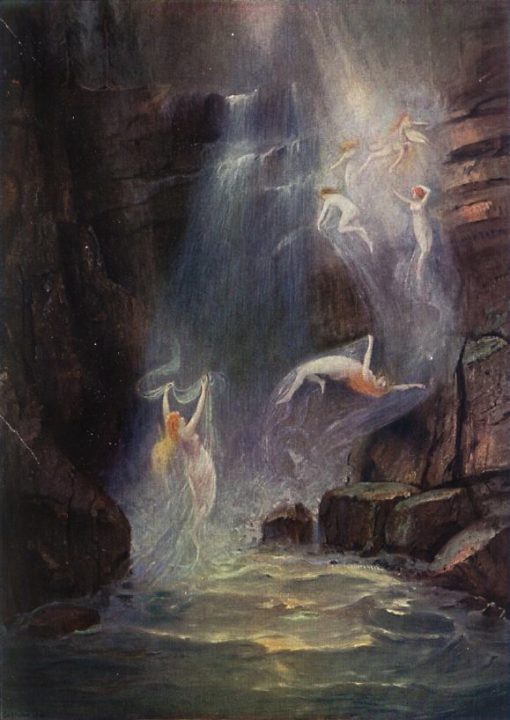

Regardless another aspect that I find a bit questionable about Heindrich’s work is related to the fact that he used his Walpurgishalle museum to sell an image about witchcraft that originally came from the Christian Middle Ages, hence linking “evil Wotan” with that particular negative perception which was/is considered “demonic”. Even if the somewhat ambiguous Wotan himself is connected to magic (via seiðr) the whole concept seems to be wrong, at least the way Heindrich portrayed it probably thinking that the whole thing was “traditional” Germanic-wise. On that particular line of thought I would recommend taking a look to the old movie The Virgin Spring (1960) by Ingmar Bergman in connection with one of the female characters in the story, known as “Ingeri”, who happens to be an “Odin-worshipping witch”.

The Germanic Spirit’s Revival

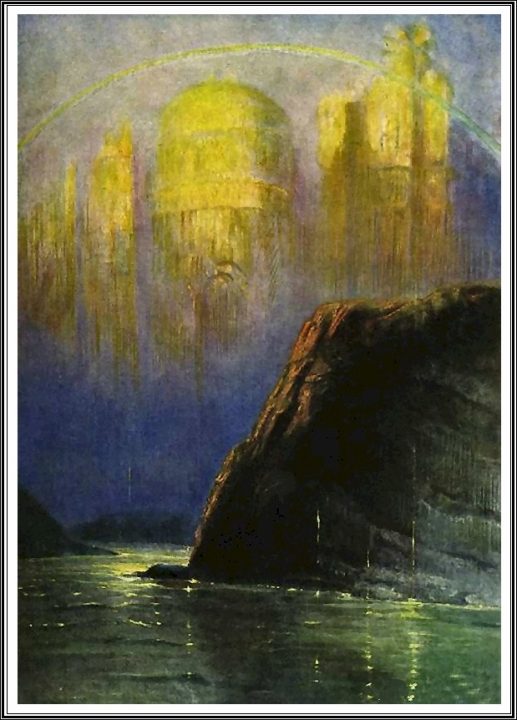

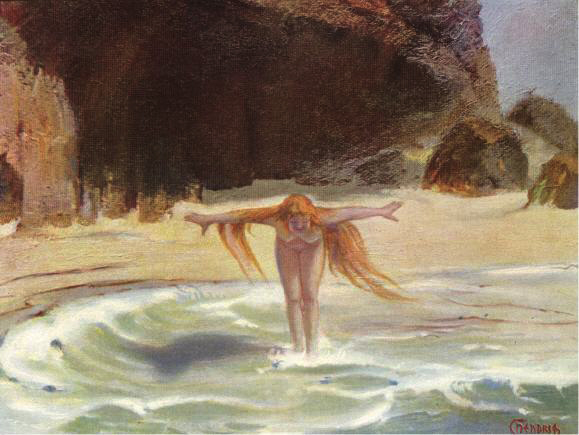

In the German art world of the turn-of-the-century a nostalgic and spiritually-driven need to recreate the themes of Romanticism -but most especially a will to revive the sacred and the mythical ancient sagas- made its apparition. Hermann Hendrich’s work was inspired by the burgeoning neo-romanticism and symbolism that heralded this artistic tendency during that time period. Together with Fidus (a.k.a. Hugo Höppener), Franz Stassen, and Ludwig Fahrenkrog, Hermann Hendrich was part of a group of young artists and painters who were strongly inspired by the idea of the Wagnerian Gesamtkunstwerk. They shared a passion for a Germanic heritage transmitted from fairy tales and sagas from the Edda which influenced many mystical and esoteric movements.

At the end of the year 1800 these artists formed the cultural milieu which, through art, literature and love for a mystical approach to nature, tried to create a new form of paganism, a philosophical and spiritual wave that we still feel reverberating these days.

Biography

Hermann Hendrich (ᛉ October 31, 1854 in Heringen, Thuringia, Germany – ᛦ July 18, 1931 in Schreiberhau in Niederschlesien, Germany) was a German painter. Hermann Hendrich was born in the vicinity of the historical Kyffhäuser, his parents were Auguste Friederike Hendrich née Ziegler and the baker August Hendrich. From 1870 to 1872 he served his apprenticeship as lithographer with one year shorter than the regular duration due to his evident talent. He then started a job in a Hanoverian lamp factory where he had to create drawings for a catalog. At that time, he attended the Wagnerian opera, Tannhäuser, which provoked in him a wish to artistically portray such musical impressions.

In 1875, Hendrich got a job at a Berlin art institution where he had to lithograph oil paintings. in 1876, he visited Norway for further art studies. However the jury of the Grosse Berliner Kunstausstellung (Great Berlin Art Exhibition) was not impressed by his paintings. Hendrich then started a job as painter in Amsterdam, the place where he met his future wife Clara (Kläre) Becker in 1882. In their honeymoon trip they visited Hendrich’s brother in Auburn, New York, where he exhibited his paintings for the first time. After some initial sales, the remaining amount of pictures was sold to a single art dealer. Using the earned money Hendrich then made a study trip through the USA.

To further deepen his education, in 1885 he went back to Germany. He started lessons with Professor Joseph Wenglein in Munich, but then moved to Berlin shortly after, making a study trip to Norway. In 1886, Hendrich entered a studio of the Berlin Academy of Art and received a stipend from the Prussian Ministry of Education and Arts. By this time his paintings were firstly exhibited in Germany. In 1889 the Kaiser himself bought a picture from Hendrich, a highlight for his recognition.

In 1901 the Walpurgishalle, a hall on the Witches’ Dance Floor near Thale in the Harz mountains, was inaugurated. Hendrich did the paintings for the interior and created sketches that were used by Bernhard Sehring to create the architecture. Hendrich considered this the apex of his career.

By 1903 in Schreiberhau Henrich erected the Sagenhalle, inspired by the Walpurgishalle. Hendrich became a co-founder of the Werdandibund in 1905, a society against the modern developments of art, which the group considered decadent. In 1910 Hendrich was awarded the title of professor.

The Nibelungenhalle at the Drachenfels was opened in 1913 on the occasion of Richard Wagner’s centenary. It contains twelve paintings by Hendrich with scenes from Der Ring des Nibelungen. The idea for the dome building came from Hermann Hendrich himself but was implemented by the Berlin architects Hans Meier and Werner Behrendt (no information on these two architects is to be found online though). In 1933 the Dragon Cave was built in the outside area of the hall, and in 1958 the Reptilienzoo was added.

In 1921, Hermann Hendrich published illustrations for an edition of Das Märchen (also known as The Green Snake and the Beautiful Lily), a 1795 story written by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe.

In 1926, the Halle Deutscher Sagenring in Burg an der Wupper (today part of Solingen) was opened. The hall exhibited Hendrich’s paintings from the Percival saga.

Hendrich died in 1931 in Schreiberhau in an accident (no more information about his death is provided). Despite accurate research on the life and works of Hendrich many aspects about his life remain unknown. Suffice to say a considerable number of Hendrich’s paintings were destroyed during WWII. Many of his early paintings were exhibited and sold in the USA, although their current location is completely unknown to this date.

Legacy

As both the Nibelungenhalle and the Walpurgishalle were showing clear signs of deterioration the buildings underwent extensive restoration and refurbishment from 2013 to 2015. By that time, Elke Rohling had the idea of forming a nonprofit organization to collect and disseminate the artistic work of Hermann Hendrich in order to preserve his architectural temples for future generations. The result of this effort has been the cultural association Nibelungenhort that produced a book and a CD of the same title on the life and works of this German artist. On November 19, 2013 in Heringen, birthplace of the artist, a plaque by “Friends of the painter Hermann Hendrich” was affixed. The inscription on the plaque reads:

“Here on October 31, 1851 was born the great German painter Hermann Hendrich”.

The above excerpts and notes are mostly taken (via wikipedia) from the book ‘Hermann Hendrich Leben und Werk’ by Elke Rohling, published by Werdandi, 2001. IBSN 3-00-008228-X. The introductory notes (that I have combined with my personal commentary) are mostly taken from the Galleria d’Arte Thule’s entry on Hermann Hendrich. In order to find more information on both the Nibelungenhalle Königswinters and Walpurgishalle Thale temples visit their respective official websites using the links provided here.

For a brief touring video of the Nibelungenhalle am Drachenfels click HERE

Sources: Galleria d’Arte Thule, wikipedia, Monumente website, Atlas Obscura, Nibelungenhalle (official website), Awayn, and Stadtjournal.

The Nibelungenhalle Königswinters and Walpurgishalle Thale temples

Today a hotel and a rest-home for a university stand in its place.

Hermann Hendrich’s art gallery

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

October 18th, 2020

October 18th, 2020  Awake Goy

Awake Goy  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: