In 2014 a construction project required Swiss anthropologist Amelie Alterauge of the University of Bern Institute of Forensic Medicine to investigate a very unusual burial in a 400-year-old cemetery. Alterauge found a middle-aged man had been laid to rest, “face-down,” with an iron knife in the fold of his arm and a purse full of coins dating back to between 1630 and 1650 AD. In a new paper published in the journal PLOS One the researcher says she suspects the man had been buried in this unusual manner so that he didn’t “return from the grave.”

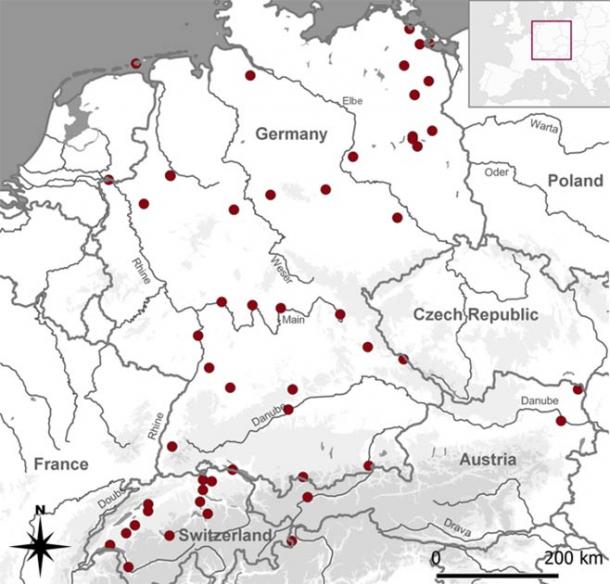

The authors of the paper researched and analyzed almost a hundred face-down (prone) medieval and post-medieval burials in Switzerland, Germany, and Austria. Their geographical distribution can be seen in the map above. Note that one site may contain sets of human remains discovered in prone position. (Jonas von Felten / PLOS One )

Fear of the Dead Returning to Haunt the Living

Alterauge and Sandra Lösch , co-author of the paper and head of the Department of Physical Anthropology at the Institute of Forensic Medicine at Bern University, researched and analyzed almost a hundred face-down (prone) burials over the course of 900 years in Switzerland, Germany, and Austria. The researchers found most of these burials dated to a time in Switzerland when the country was ravaged by plagues. The circumstances of these face down burials were comparable with “mutilation or weighing bodies down with stones.”

These strange burial methods, according to an article about the new research on National Geographic , were designed to “thwart vampires and the undead by preventing them from escaping their graves.” The new study demonstrates a major shift in burial practices across Europe beginning in 1347 AD, a time when the plague was sweeping across Europe killing millions of people, and people had come to believe that plague victims might “come back to haunt the living.”

At a time when the plague was sweeping across Europe killing millions, people began to fear that plague victims might come back to haunt the living. Image from the Nuremberg Chronicle, an illustrated encyclopedia completed in 1493. ( Public domain )

Fearing the Undead: Seeing and Hearing the Stirring Dead

It is one thing to see a living, plague infected person, and to describe them as resembling the undead. But what on earth would make people think that folk actually returned from the grave? In the paper, Alterauge explains that the plague killed people faster than communities could cope with. Corpses “would bloat and shift, and gas-filled intestines of the dead made disturbing, unexpected noises.” Furthermore, as flesh decays the hair and nails of corpses would have seemed “to grow” as the flesh around them shriveled up. Unpleasant as it may sound, decaying bodies “move” and “make smacking sounds.” All of this would have contributed to the belief in what we would today call zombies. It might even seem as if the corpses were “eating themselves and their burial shrouds,” Alterauge says.

Trying to account for all these post-death movements and sounds, it is thought that medieval Europeans adopted Slavic ideas about the dead returning to life. Alterauge goes on to explain that while there was no “concept of vampires in Germany,” tales of the undead were imported into western Europe from Slavic areas at the time of the first plague outbreak in the mid-1300s. Matthias Toplak , an archaeologist at the University of Tübingen in Germany, told National Geographic that a “shift to evil spirits” occurred around 1300 or 1400 AD. In pandemic-era Europe the legend had a compelling logic: “As the victim ’s close relatives began developing symptoms and collapsing within days of the funeral, it must have seemed as if they were being cursed from the grave.” Therefore, burying some one facedown, or prone, was an attempt to disable the dead from returning to infect survivors.

“As the victim ’s close relatives began developing symptoms and collapsing within days of the funeral, it must have seemed as if they were being cursed from the grave”. Detail of the wax statue entitled “The Plague” by Gaetano Giulio Zumbo. ( I, Sailko / CC BY-SA 3.0)

A Fear of God or Medieval Zombies?

Not everyone is convinced, however, that prone burials were performed to thwart the undead from returning to the land of the living. Petar Parvanov , an archaeologist at Central European University in Budapest , told National Geographic that in a world ravaged by deadly pandemics community ’s may have buried their first victim face-down as a desperate, if not symbolic, attempt to ward off further infections. Parvanov also suggests that when someone got infected, churchmen may have pushed the idea that the disease was a punishment from God. Prone burials could have demonstrated how much sin was present in their communities, in order that they would “want to show penance.”

All that remains for us to do is to decide which is the most likely inspiration for these face down burials : was it a tactic to trick the returning undead, as the new paper suggests, or was it a social response to the fear-mongering created by greedy churchmen? We are left to ponder whether this spike in face-down burials was caused by a fear of God or medieval zombies.

Top image: Photograph of a face-down burial, also known as a prone burial, in a churchyard in Berlin, just one of almost a hundred medieval and post-medieval burials in Switzerland, Germany, and Austria included in the study. Source: ( Claudia Maria Melisch / Landesdenkmalamt Berlin )

By Ashley Cowie

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

September 5th, 2020

September 5th, 2020  Awake Goy

Awake Goy  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: