THESSALONIKI, GREECE (Analysis) – While international media outlets focused on the women’s rallies of this past weekend, in Greece a population that for several years has not participated in any large-scale protests came out in force on Sunday. Greeks gathered to oppose a deal between Greece and the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia (FYROM) — the country’s official name as per the United Nations — that would allow Greece’s northern neighbor to officially include Macedonia in its name. The demonstration flooded the streets of downtown Thessaloniki — the capital of the Greek province of Macedonia, and Greece’s second largest city.

Official estimates for the turnout ranged from 90,000 according to the police to over 500,000 according to rally organizers. What is indeed evident is that turnout was likely far closer to the organizers’ estimates than to those of the police. Photos from the rally show the crowd of demonstrators stretching from the White Tower, Thessaloniki’s main landmark, all the way to the Thessaloniki Music Hall in one direction and to Aristotelous Square in the other, spanning almost two miles along the city’s coastline. Busloads of protesters traveled from all corners of Greece, with over 500 coach buses reportedly delivering participants to Thessaloniki just from Athens alone.

Sunday’s rally signified Greece’s biggest demonstration, by far, since the period leading up to the country’s July 2015 austerity referendum, following a long period of relative dormancy. Joining the Thessaloniki protesters in spirit, members of the overseas Greek communities — in cities such as London (outside the British Parliament), Stuttgart, and Melbourne — came out in significant numbers and participated in rallies organized locally.

For many, Sunday’s rally — and the opposition of many Greeks to the use of the name “Macedonia” by the country’s northern neighbor — reeks of nationalism and ethnocentrism. And indeed, many right-wing and even far-right elements were behind the official organization of Sunday’s rally. This nationalist and ethnocentric view, however, does not represent the ordinary public that participated in the protest, many of whom also represented those with a more left-wing political outlook (including dozens of people I personally am acquainted with). Although left-wing, however, that outlook is opposed to the government led by the neoliberal, pro-EU, pro-austerity “leftist” SYRIZA party, as well as to the Communist Party of Greece — which denounced Sunday’s rally and which, on and off, has recognized Greece’s northern neighbor as “Macedonia.”

Furthermore, this view glosses over numerous historical realities and, even more significantly, geopolitical realities in the region — and the role and ambitions of the United States and NATO in the wider Balkan region. This piece will briefly examine the historical development of the Macedonia dispute, the current negotiations and geopolitical forces at work, and the stance of the Greek government and establishment at the present time. Moreover, the efforts to downplay Sunday’s rally and to characterize an entire mass of protesters as “fascist,” will be analyzed.

Redrawing the Balkans: the birth of a “Macedonian” state

Contrary to what is often reported, the area now known as FYROM was not always officially named “Macedonia.” Indeed, it was not called Macedonia until after World War II, when it was a province of Yugoslavia and was renamed “Macedonia” by Yugoslav leader Tito, with the approval of Stalin and the Soviet Union. Previous to that, in the early 20th century, the region was successively known as South Serbia, then absorbed within Bulgaria, then known as “Vardarska,” named after the main river running through the region.

As pointed out by analyst Vasilis Viliardos, while this name change may have initially seemed to be an internal Yugoslav matter, it was anything but. Tito’s grand plan for the region was for a greater Yugoslav nation, one that would include “Macedonia” and stretch all the way to the shores of the Aegean and the city of Thessaloniki. In order to achieve these aims though, a Macedonian “nationhood” first had to be invented, one that would co-opt the ancient history of Macedonia.

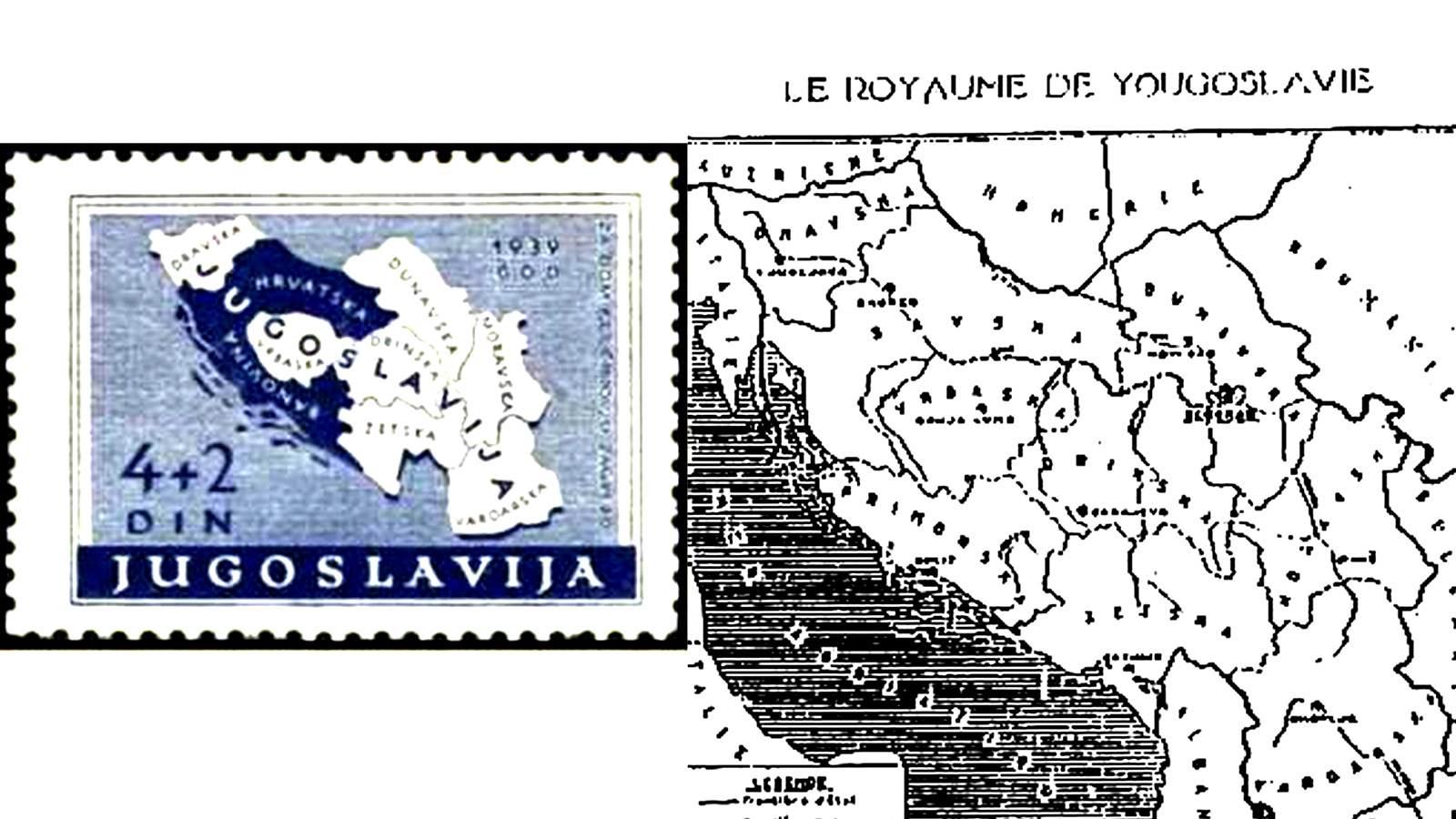

The historical record provides evidence for these early efforts at revisionism. While, for instance, a 1937 map of Yugoslavia and a 1939 Yugoslav stamp illustrate modern-day FYROM as “Vardarska,” by the 1940s the Yugoslav authorities were actively promoting the region as “Macedonia.” A July 10, 1946 article appearing in The New York Times states “a ‘Federal Macedonia’ has been projected as an integral part of Tito’s plan for a federated Balkans…taking Greek Macedonia for an outlet to the Aegean Sea through Salonica.”

A Yugoslav stamp circa 1939 showing ancient Paionia labeled ‘Vardarska’. A map depicting Yugoslavia circa 1937 is pictured on the right.

Two weeks later, a July 26, 1946 article in the Times by C.L. Sulzberger stated: “The possible creation of a Macedonian free state within Greece to amalgamate with Marshal Tito’s Federated Macedonia State, with is capital in Skopje…would fulfill the Slavic objectives of re-uniting the…province of Macedonia under Slavic rule, giving access of the sea to Bulgaria and Yugoslavia.”

Such expansionist plans on the part of Tito’s Yugoslavia were also recorded in U.S. diplomatic cables of that era, including a December 26, 1944 cable that stated:

The [State] Department has noted with considerable apprehension increasing propaganda rumors and semi-official statements in favor of an autonomous Macedonia, emanating principally from Bulgaria, but also from Yugoslav Partisan and other sources, with the implication that Greek territory would be included in the projected state. This Government considers talk of Macedonian ‘nation,’ Macedonian ‘Fatherland,’ or Macedonia ‘national consciousness’ to be unjustified demagoguery representing no ethnic nor political reality, and sees in its present revival a possible cloak for aggressive intentions against Greece. …

The approved policy of this government is to oppose any revival of the Macedonian issue as related to Greece. The Greek section of Macedonia is largely inhabited by Greeks, and the Greek people are almost unanimously opposed to the creation of a Macedonian state. Allegations of serious Greek participation in any such agitation can be assumed to be false. This Government would regard as responsible any Government or group of Governments tolerating or encouraging menacing or aggressive acts of ‘Macedonian Forces’ against Greece.”

Tito’s grand plan for “Macedonia” indeed began to be implemented following World War II. Starting in the 1950s, theories began to develop about the ancient origins of the “Macedonian people” as direct descendants of the likes of Alexander the Great and Philip II of Macedonia — even though, anthropologically, the inhabitants of what is today FYROM are descended from peoples that settled in the area in the sixth to seventh century A.D., a near millennium after the era of Alexander the Great. This is not meant to be an ethnocentrist argument in either direction, merely a statement of fact supported by the historical record.

The discontinuity between the ancient Macedonians and those who today refer to themselves as “Macedonian” (and are attempting to co-opt this ancient history as their own) was admitted to by none other than former president of FYROM Kiro Gligorov, who stated in an interview with the Toronto Star in 1992:

We are Macedonians but we are Slav Macedonians. That’s who we are! We have no connection to Alexander the Great and his Macedonia. The ancient Macedonians no longer exist, they had disappeared from history long time ago. Our ancestors came here in the 5th and 6th century (A.D.).”

In a similar vein, the former prime minister of FYROM, Ljubco Georgievski, has stated, in a televised interview, that the ancient Macedonian people were Greek.

Nevertheless, landmarks in what is today FYROM began to be renamed after ancient figures and symbols. Statues of Alexander the Great were constructed, and the country’s main international airport now bears his name. FYROM’s original map, following independence, bore the Vergina Sun — a popular ancient Greek symbol inscribed on ancient tombs in the Greek region of Vergina, said to be the burial site of King Philip II and possibly Alexander the Great or his brother. This symbol was later changed on FYROM’s flag to a nonspecific sun with rays emanating from it, as part of an agreement between the two countries in 1995 that also set the constitutional, temporary name of Greece’s northern neighbor as FYROM.

Read more by Michael Nevradakis

- Google, Facebook, Twitter Clamor for an “Open Net” While Gearing Up Their Censorship Divisions

- “Sellouts in the Room:” Éric Toussaint on the Greek Debt Crisis and SYRIZA Betrayals

- The Trials of Andreas Georgiou and the Fraud That Drove Greece into Austerity

- An Insider’s View of SYRIZA-Led Greek Capitulation to EU Blackmail

Nationalist zeal was fostered amongst the population of this region, based on this ancient “heritage.” And as part of this nationalist zeal, expansionist propaganda also began to appear, including maps displaying a “greater Macedonia” in place of FYROM, extending into Greek territory and up to the Aegean shoreline.

In August 2015, for instance, the then-parliamentary vice president and former foreign minister of FYROM, Antonio Milososki, appeared at an event in Ontario organized by members of FYROM’s diaspora, speaking in front of a map displaying “greater Macedonia,” which included a significant chunk of Greek territory, including Thessaloniki. FYROM’s ambassador to Canada appeared in front of this same map at an event in Toronto in 2016. Elementary school classrooms in FYROM have been painted with the map of “greater Macedonia,” while the map of “greater Macedonia” has also been used in advertisements by FYROM diaspora organizations, such as in an advertisement appearing in the Toronto Star on July 31, 2014.

But how did FYROM, as an independent state, come about and adopt the name “Macedonia”? Following the collapse of the Soviet Bloc and the breakup of the former Yugoslavia, “Macedonia” declared independence in 1991, claiming both the name “Macedonia” and the Vergina Sun as its national symbol, in the new country’s flag. And it is here where geopolitics really comes into the picture.

Another NATO-U.S. client state in the Balkans?

NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg, second from left, accompanied by Macedonian Prime Minister Zoran Zaev, left, inspects an honor guard squad upon his arrival at the Government building in Skopje, Macedonia, Jan. 18, 2018. NATO’s secretary-general urged Macedonia to solve its name dispute with Greece and proceed with wide-ranging reforms if it wants its membership bid to succeed. (AP/Boris Grdanoski)

The breakup of the former Yugoslavia — initially achieved in the early to mid-1990s and since progressing with the formation of Montenegro and Kosovo as independent states — has been closely tied in with U.S., NATO, and European Union foreign policy and geopolitical ambitions in the area. Following the fall of the “iron curtain,” a main objective of strategists in Washington and Brussels was to wrest control of the Balkans away from Russian influence, bringing the entire region into the Western sphere.

Taking advantage of a disemboweled Russia in the aftermath of the USSR’s collapse, nationalist tensions were stoked, civil wars were fomented, and Yugoslavia dissolved into war, crisis and, eventually, a number of small, weak states. Decimated following the collapse of communism and the sufferings of civil war, states such as Croatia, Bosnia, and FYROM were the perfect clients for the West’s imperial ambitions in the Balkan region. Illustrating the region’s significance, it has been noted, for instance, that the new U.S. embassy in Skopje, the capital of FYROM, is the largest U.S. embassy in the world.

As part of such efforts, imperial powers stoked and then harnessed nationalist tendencies that had been fomented in FYROM, essentially trading diplomatic support of such ambitions for geopolitical and military cooperation. One of President George W. Bush’s first acts upon commencing his second term in office, for instance, was formal recognition of FYROM as the “Republic of Macedonia.” In all, 130 countries have recognized FYROM by this name, even as its official United Nations name remains “Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia.” China is one such country, as well as traditional Greek allies — deriving from cultural proximity if nothing else — Russia and Serbia.

“Macedonia’s” declaration of independence led to developments in Greece as well, and arguably contributed to the downfall of the government led by the center-right New Democracy party, which was hanging on to a flimsy one-seat parliamentary majority and which was seen by many in Greece as not putting up enough diplomatic resistance to the naming issue. A rally held in Thessaloniki, on February 14, 1992 drew up to a million protesters and is arguably the largest such demonstration held in the history of post-war Greece. The government collapsed a year later, as members of New Democracy’s parliamentary faction, angered over Prime Minister Constantine Mitsotakis’ willingness to compromise regarding the name dispute, broke off and formed a splinter party, Political Spring, which eliminated New Democracy’s parliamentary majority and eroded its support in the snap parliamentary elections of October 1993.

The now-deceased Mitsotakis’ government may have collapsed, but one of his quotations lives on in infamy today. In February 1993, in a stunning display of arrogance, Mitsotakis, in reference to the Macedonia name dispute, predicted that the Greek people “will have forgotten about it in 10 years.” And just as Mitsotakis evidently held the Greek populace that elected him in such low esteem, today’s current “leftist” SYRIZA-led government apparently harbors similar feelings, as will be demonstrated.

Matthew Nimetz: The hardly neutral mediator

Matthew Nimetz, the UN mediator in the name dispute between Macedonia and Greece, answers journalists’ questions following his talks with Macedonian officials in Skopje, Macedonia, Sept. 11, 2013. (AP/Boris Grdanoski)

Despite the collapse of the New Democracy-led government in Greece, a diplomatic stalemate ensued, and the Clinton administration, which was actively involved in the ongoing developments in the Balkans during this period, appointed Matthew Nimetz as its Special Envoy for the Macedonia name dispute in March 1994. The negotiations that followed resulted in a temporary compromise agreement in September 1995, where the name “FYROM” was established, the country’s flag was changed, and diplomatic relations between FYROM and Greece were restored while a final resolution regarding the name dispute was left for a later date. Former U.S. Secretary of State Cyrus Vance chaired continued talks regarding the dispute, with Nimetz serving as Vance’s deputy, before being appointed as the UN secretary-general’s Personal Envoy for the Macedonia dispute in December 1999 — a position that Nimetz still holds today.

Who is Matthew Nimetz? An examination of his background reveals a long and fascinating history of serving what can be described as globalist and imperialist aims. Fresh out of Harvard Law School, where he served as editor of the Harvard Law Review, Nimetz clerked for Supreme Court Justice John Marshall Harlan II from 1965 to 1967. Harlan was, quite notably, in 1937 one of the five founders of the Pioneer Fund, an organization that promoted the practice of eugenics, of which the Nazi regime in Germany was a strong proponent. Indeed, at least two of the group’s five founders are said to have held close ties to Nazi Germany, while Harlan served on the organization’s board for several years.

Nimetz then joined the administration of President Lyndon B. Johnson in 1967. While Nimetz was tasked with domestic policy, it was the Johnson administration that, in 1967, supported a coup in Greece that established a dictatorial military regime that reigned until 1973. President Johnson himself, in 1965, had been quoted as stating the following to Greece’s ambassador, when the latter rejected Johnson’s plan to divide Cyprus into Greek and Turkish parts, as a solution to the ongoing disputes between the two countries:

Fuck your Parliament and your constitution. America is an elephant. Cyprus is a flea. Greece is a flea. If those two fleas continue itching the elephant, they may just get whacked… We pay a lot of good American dollars to the Greeks, Mr. Ambassador. If your prime minister gives me talk about democracy, parliaments, and constitutions, he, his parliament, and his constitution may not last very long… Don’t forget to tell old papa-what’s his name what I told you [referring to Greek Prime Minister Giorgos Papandreou].”

From 1975 to 1977, having returned to the private sector, Nimetz was appointed as a Commissioner of the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, the entity that controls the New York metro area’s three international airports, its seaports, and its main bus terminal — and that owned the World Trade Center (and owns 1WTC today). Nimetz was again appointed as a Commissioner of the Port Authority in 2007 by then-Governor Eliot Spitzer of New York, but Spitzer’s sex scandal and subsequent resignation prevented Nimetz’s nomination from proceeding.

Upon his return to government service in 1977, Nimetz worked under Cyrus Vance at the State Department and was tasked with the Greek-Turkish disputes, including the Turkish invasion and occupation of almost 40 percent of Cyprus (which continues to this day), the Micronesian status negotiations (which are said to have stymied any hopes for Micronesian independence, while essentially creating pro-U.S. dependencies in the Pacific), and, interestingly enough, Mexico-United States border issues. In 1979, Nimetz was then promoted to the position of Under Secretary for Security Assistance, Science and Technology, which included in its purview the U.S. government’s international communications activities. He also continued to supervise U.S. policy in the Eastern Mediterranean region.

Notably, during Nimetz’ tenure at the State Department, the United States’ arms embargo against Turkey — which had been imposed in February 1975, not long after Turkey’s invasion and subsequent occupation of a significant portion of Cyprus — was overturned.

Nimetz is also a member of the board of advisers of the National Committee on American Foreign Policy (NCAFP). In the past, the committee has seen fit to present awards to the likes of Henry Kissinger, Margaret Thatcher, the aforementioned Cyrus Vance, former New York governor Hugh Carey (on whose campaign staff Nimetz served), and Richard Holbrooke, who was intimately involved in the Yugoslav conflict in the 1990s.

Interestingly, Nimetz, as of 2017, serves as a trustee of the George Soros-founded Central European University (CEU) in Budapest, an institution founded following the collapse of the Iron Curtain as part of Soros’ “open society” initiatives in Central and Eastern Europe. Kati Marton, wife of the late Richard Holbrooke, serves as a trustee of the CEU. Soros chaired the CEU until 2009 -– his replacement, Leon Botstein, had served as president of Bard College in New York.

It should be noted that Bard College is the home of the Levy Economics Institute, founded in 1986 by economist Dimitris B. Papadimitriou, who also served as the Institute’s longtime president and who is presently Greece’s minister of economy and development. Papadimitriou’s wife, Ourania (Rania) Antonopoulos, Greece’s alternate minister for combating unemployment, also served as a senior economist at the Levy Institute and taught at Bard College. She has also been closely affiliated with the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP).

The UNDP and the CEU are, in turn, both listed as donors for an outfit known as the Centre for Democracy and Reconciliation in Southeastern Europe (CDRSEE), based in Thessaloniki. Nimetz has served as a director and founding chair of this organization, which, among other initiatives, has promoted a “Joint History Project” with the support of the EU. This project is described as an effort to “change the way history is taught in schools in the Balkans,” and one might be tempted to wonder whether such a “joint history” includes, for instance, a “joint history” of Greece and “Macedonia.”

Notably, the CDRSEE counts as its donors, aside from the UNDP and CEU, entities such as the U.S. State Department, USAid, the National Endowment for Democracy, the British Foreign and Commonwealth Office, the “Foundation Open Society Macedonia,” the European Union, the European Commission, and the municipality of Thessaloniki, under the auspices of its mayor, Yiannis Boutaris.

A darling of neoliberals worldwide, Boutaris has received glowing coverage from The Guardian, The New York Times, The Telegraph, Der Spiegel, Die Zeit, NPR, and Global Risk Insights, while he was shortlisted for World Mayor 2014. He has characterized Greece as a “Soviet-type society;” stated that he is ashamed to be Greek; called himself a “star mayor;” and repeatedly referred to FYROM as “Macedonia.”

Referencing Sunday’s rally in Thessaloniki, Boutaris has stated that “in Skopje no rallies are being organized, we [Greeks] will never learn,” while describing the rally as “devoid of substance” and “harmful for negotiations” between the two countries.

Nimetz, as demonstrated above, clearly maintains strong and direct ties to a number of different organizations and figures who, it could be argued, undermine Greece’s position in its dispute with FYROM over the name “Macedonia.” And it is Nimetz who is the UN’s mediator for the dispute between the two countries.

This is not an unfounded concern for many Greeks. Nimetz, in an interview broadcast last week on Greece’s Antenna TV, essentially used the aforementioned interim agreement of 1995 — which he himself chaired as President Clinton’s Special Envoy and where the name “Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia” was adopted — as a negotiating position against Greece, stating:

One has to be realistic. Right now the name of the country in the United Nations is Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia. So the name Macedonia is in the name now in the United Nations and recognized by Greece with that name. Over 100 countries recognize the name as Republic as Macedonia, so it has Macedonia in the name, for most countries.”

Redrawing the Balkan map once more?

A group of people hold banners reading “We are Macedonia” during anti NATO protest in front of the Parliament in Skopje, Macedonia, while NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg addressed lawmakers in Parliament, Jan. 19, 2018. (AP/Boris Grdanoski)

Some actors are no longer sharing Nimetz’s enthusiasm over the recognition of FYROM as “Macedonia” by “most countries.” Earlier this month, Serbian foreign minister Iviva Dacic stated in an interview that “[w]e’ve been fools to recognize Macedonia under that name” and that Serbia “made a mistake when it recognized that country under its constitutional name (‘Republic of Macedonia’),” due to FYROM’s subsequent recognition of Kosovo’s independence. Dacic added:

Serbia made a big mistake there. All of Europe and the world are using the name ‘Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia’ (FYROM), whereas we slapped our brothers the Greek, and now expect the Greek not to recognize Kosovo, while we recognized Macedonia by insulting the Greek, and they (Macedonians) are always voting in favor of Kosovo. I must say, we’ve been the fools. There, I’ll use an undiplomatic term.”

Dacic’s comments may be more than just undiplomatic. They may reflect broader changes that may be afoot in the Balkans, which are intimately tied to the future fate of FYROM, regardless of name.

In 2015, a protracted political crisis commenced in FYROM, resulting from a corruption and wiretapping scandal that impacted the ruling nationalist, center-right VMRO-DPMNE government. Large-scale protests were organized in FYROM in both 2015 and 2016, which have been likened to “color revolutions” seen in other countries in Eastern Union and Central Asia. Snap parliamentary elections were called in 2016, but were postponed twice before being held on December 11, 2016.

The protracted political crisis continued, however, as no clear winner emerged from the polls. After months of political stalemate, the second-place “social democratic” SDSM party was given a mandate to form a government, immediately after the visit of U.S. Deputy Assistant Secretary for European and Eurasian Affairs Hoyt Yee. Ironically, this regime change has prompted the development of a new “stop Soros” movement in FYROM, as there are some who consider the country’s new government as subservient to or controlled by the financial and geopolitical interests of George Soros.

Geopolitical analyst Andrew Korybko has, since 2016, repeatedly predicted that FYROM would fall victim to Western-induced “hybrid warfare,” of which the snap elections and formation of a SDSM government are allegedly a part. This “hybrid warfare” would have, as its end result, the split of FYROM into two, with one half joining a new Albanian federation (which Kosovo may also join, and which will surely provoke a response from Serbia), and the other half joining Bulgaria. A possible step towards the latter outcome is a treaty signed between FYROM and Bulgaria, which Korybko has argued opens the door for FYROM to be subsumed by its Eastern neighbor in the event of a “crisis.”

In the meantime, the parliament of FYROM recently passed legislation making Albanian the country’s second official language, though this legislation was later vetoed by FYROM’s president, Gjorge Ivanov. It should not be overlooked that Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov stated in 2015 that Bulgaria and Albania want to divide FYROM between themselves.

Another possible indicator of looming instability is reflected in the actions of both Russia and China, which previously eyed FYROM for strategic projects in the region. The Russia-backed Balkan Stream natural gas pipeline and the China-backed Balkan Silk Road high-speed railway were both slated to traverse FYROM on their way to central Europe.

Korybko argues, however, that both Russia and China seem to be entertaining second thoughts about these projects, with Russia eying an alternate pipeline route through Bulgaria, while China is considering an alternate route for its railroad, which would still begin from the Chinese-owned port of Piraeus in Greece (privatized in 2016 by the “anti-privatization” SYRIZA-led government) but would be rerouted through Bulgaria. These changes, according to Korybko, are as a result of the risk of crisis or instability in FYROM, which both Russia and China are increasingly wary of.

Perhaps further reflecting this new geopolitical posture towards FYROM, Lavrov stated recently his belief that Greece should not make any concessions regarding the Macedonia name.

It may also be the case that the new Rex Tillerson-led State Department, along with NATO, are seeking to put their own stamps on pending matters in the Balkans, and may consider the ongoing dispute and political uncertainty involving FYROM to increasingly be a liability for Western interests in the region. In 2008, Greece, a member of both the EU and NATO, vetoed FYROM’s bid for NATO membership, citing the unresolved name dispute. It is surmised that a similar action could be undertaken by Greece to block FYROM’s EU aspirations if the Macedonia dispute remains unsolved. This may be considered by the State Department and NATO to be more trouble than it’s worth, resulting in further developments and a possible redrawing of boundaries in the region.

Interestingly — echoing both the fall of the Mitsotakis government in 1993 following the Macedonia name crisis, and the fall of the previous center-right government in FYROM following a wiretapping and corruption scandal — the center-right government of Prime Minister Konstantinos Karamanlis, which vetoed FYROM’s NATO candidacy and which pursued a foreign policy that was more open towards Russian interests, itself was beset by a wiretapping scandal and by what seemed like a constant stream of political and even sexual scandals, followed by the violent December 2008 riots in Athens, before collapsing in 2009.

The newly-elected government of George Papandreou, grandson of the aforementioned “Papa-what’s his name” of Lyndon B. Johnson fame, delivered Greece’s first austerity agreement and brought the International Monetary Fund (IMF) to Greece. He further has been accused of falsifying Greece’s debt and deficit figures — specifically, inflating them — in order to provide the political and economic impetus to place Greece under international financial oversight.

Protesting more than just a name

People walk between Greek flags ahead of a rally against the use of the term “Macedonia” for the northern neighbouring country’s name, at the northern Greek city of Thessaloniki, Jan. 21, 2018.(AP/Giannis Papanikos)

This brings us to present-day Greece, mired in its ninth year of the economic crisis — with no real end in sight, despite the cheery claims of the SYRIZA-led coalition government that Greece will exit the memorandum agreements later this year and return to a period of economic stability. Such optimism is not reflected on the ground, however, and it was perhaps a matter of time before ordinary Greeks, after a period of dormancy, started to lash out.

Sunday’s rally may have been such a moment. Despite rampant accusations that the rally represented runaway nationalism and fascism, at its heart it could actually be considered as an anti-imperialist rally, at least from the perspective of many attendees — the response of a populace that is finally tired of what it considers to be a political system that is soft on issues of national interest, and of the indignity of being a pawn in the regional chess match of great imperialist and Western powers.

More than this though, the rally also represents an expression of increasing frustration with the economic realities and struggles in Greece today. Speakers at the rally on Sunday did not restrict themselves to the Macedonia name dispute. They also addressed the privatization of national assets, of airports and harbors, by a government that had once promised to put an end to this sell-off. They addressed the economically dubious and environmentally destructive gold mining operations in Skouries (not far from Thessaloniki). And they addressed the home foreclosures and auctions — which are set to increase this year with the seizure even of households’ primary residences and with the introduction of electronic auctions, replacing courthouse auctions that have often been stymied by a well-organized movement that has sought to prevent them.

In short, speakers at Sunday’s rally addressed many of the major concerns on the minds of most Greek citizens today.

It is perhaps for this very reason that the Macedonia name dispute has suddenly returned to the forefront again, after years of being a diplomatic afterthought. As evidenced above, both Greece and FYROM are facing, each in its own way, a great deal of domestic turbulence. Returning a somewhat forgotten, culturally symbolic national issue to the fore can be seen as a great distraction from other, everyday troubles and concerns of ordinary citizens. Not surprisingly, numerous arguments against organizing the mass rally in Thessaloniki have centered on the “need for unity” at a time when the Greek government is “engaged in sensitive negotiations” on “an issue of national importance.”

Just as the Greek parliament is comprised of parties whose positions are, in fact, unrepresentative of Greeks’ attitudes towards the economic crisis and Greece’s continued membership in the Eurozone and the European Union, the same is evident with respect to Greek citizens’ views regarding the Macedonia issue. Though most public opinion polls in Greece should be taken with many grains of salt, as they are conducted by state-funded polling firms and on behalf of oligarch-owned, pro-austerity, pro-EU, and pro-NATO media outlets, several recent polls nevertheless showed wide majorities opposing any Greek compromise on the Macedonia name.

In a survey conducted by polling firm Marc, 68 percent of respondents (including, interestingly, 64 percent of SYRIZA voters) opposed a compromise. A poll conducted by online portal zougla.gr found 79 percent of respondents not in favor of a compromise. And a Metron Analysis poll found that between 77 and 82 percent of respondents opposed various proposed “composite names” for FYROM, such as “North Macedonia” or “New Macedonia,” while 61 percent of respondents favor a national referendum on any deal concerning the naming issue.

Of course, what major Greek and foreign media outlets instead chose to focus on was one single survey, conducted by polling firm Alco on behalf of radio station “Radiofono 24/7,” which found that 63 percent of respondents were in favor of a compromise solution on the Macedonia name dispute. It bears noting here that “Radiofono 24/7” is owned by up-and-coming oligarch Dimitris Maris, who maintains extremely close ties with SYRIZA. His media outlets — which also include online portal news247, the Greek edition of the Huffington Post, the newspaper Dimokratia, and the management of national newspapers Ethnos and Imerisia on behalf of their new owner, Russian-born oligarch Ivan Savvidis, himself close to SYRIZA — are unabashedly favorable towards the current Greek government.

Indeed, Maris’ outlets participated in the political and media blitz against the forthcoming rally in Thessaloniki in other ways as well, with Greek Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras providing a softball interview to Ethnos and Radiofono 24/7 a few days prior to the rally. In this interview, Tsipras warned of the dangers of not reaching an agreement swiftly, justifying this stance by claiming he is “half [Greek] Macedonian.”

In turn, main opposition party New Democracy, currently ahead of SYRIZA in all published public opinion surveys, is said to have “suggested” to members of the party not to appear at Sunday’s rally. Nevertheless, numerous members of New Democracy are said to have been present at the demonstration.

Greek Orthodox Archbishop Ieronimos joined the chorus. After meetings with Tsipras and with the president of the Hellenic Republic, Prokopis Pavlopoulos, Ieronimos stated publicly that “now is the time for national cooperation, not rallies,” while discouraging clerics from participating in Sunday’s rally. Nevertheless, this call went unheeded by many within the church: one local diocese is reported to have sent 60 busloads of parishioners to the rally.

The leader of the Communist Party of Greece (KKE), Dimitris Koutsoumbas, in a radio interview prior to the rally, stated that “there is no need for nationalist rallies” at this time, while longtime member of parliament with the KKE, Liana Kanelli, warned those thinking of attending the rally that if a solution is not reached that is to NATO’s satisfaction, war will follow in the Balkans.

Even smaller, non-parliamentary and purportedly anti-imperialist and anti-austerity parties could not help revealing what may perhaps be their true sympathies. The far-left ANTARSYA, in a statement that carefully avoided any specific reference to Greece’s northern neighbor by any name, denounced the “nationalist” rallies while calling for NATO’s ouster from the Balkans. The president of the United People’s Front (EPAM), Dimitris Kazakis, in a radio interview prior to the rally, announced his position in favor of abstention from the rally — on the grounds that it did not call into question NATO and the EU, even though as it turned out, speakers at the rally did speak against and question austerity, privatizations, and other EU-imposed “measures.”

Rally-goers faced concerted campaign of obstacles and discouragement

Thousands of protesters take part in a rally against the use of the term “Macedonia” for the northern neighboring country’s name, at the northern Greek city of Thessaloniki, Jan. 21, 2018. Over 100,000 Greeks gathered in the northern city of Thessaloniki to demand that the term “Macedonia,” the name of the Greek province of which Thessaloniki is the capital, not be used by Greece’s northern neighbor known by the same name. (AP/Giannis Papanikos)

It could, in fact, be argued that there was a concerted effort amongst the political and media establishment to prevent the rally or to discourage people from attending. Indeed, leading up to the rally, estimates of its turnout heard on the Greek media were rather low, ranging from 10,000 to 20,000, while potential attendees were also warned of poor, rainy weather, which was forecast for Thessaloniki on Sunday (the rain never materialized).

The obstacles continued even on the day of the rally. Numerous reports on social media from ordinary attendees reported that toll booths on the main highway leading to Thessaloniki that were closest to the city — the state-owned tolls in the Malgara region — were closed early Sunday, leading to tremendous delays. Many buses reportedly reached Thessaloniki later than planned as a result, and many of these buses are said to have been stopped by authorities in Kalohori, a suburb of Thessaloniki five miles from downtown, forcing many participants, including the elderly and disabled, to walk the rest of the way. There were also several reports of cell phone networks being unavailable in downtown Thessaloniki for the duration of the protest. Notably, each of Greece’s three cellular carriers is foreign-owned.

Media coverage of the rallies was also limited. Live coverage was not provided by public broadcaster ERT — which, just a few years earlier in 2013, had organized rallies of its own when it was shuttered by the previous New Democracy-Panhellenic Socialist Movement (PASOK) government, with its Thessaloniki studios acting as a hub for such protests for two years until ERT was reopened. Private stations did not provide live coverage either — save for a local, Thessaloniki-based station, Vergina TV, and a very small number of other such local stations throughout Greece, which rebroadcast an internet stream of the rally.

Writing off the rally with simplistic, pejorative labels

Protesters at a rally against the use of the term “Macedonia” for the northern neighboring country’s name, at the northern Greek city of Thessaloniki, Jan. 21, 2018. (AP/Giannis Papanikos)

When all of that did not have a tangible negative impact on the rally, the political and media spin began. SYRIZA condemned the rally, characterizing it in an official statement as “a triumph of fanaticism, nationalism, and intolerance.” Government spokesman Dimitris Tzanakopoulos, in reference to the rally, said that “ethnic paternalism and exceptionalism” harm Greece’s position. Deputy Foreign Minister Yiannis Amanatidis, whose ministry is supposedly negotiating on Greece’s behalf, argued in a Skai TV interview that “140 countries recognize FYROM as ‘Macedonia,’ why not us?”

In turn, Alternate Foreign Minister George Katrougalos, a “constitutional scholar” who in 2011 was an active participant in the major protests against austerity in Greece, stated that those who disagree with a compromise that includes usage of the name “Macedonia” are “extremists and nationalists,” and that it would be a “patriotic solution” to include “Macedonia” in a compromise agreement.

Continuing the chorus, Deputy Defense Minister Dimitris Vitsas deemed the rally “an expression of nationalism,” Transport Minister Christos Spirtzis described the participants in the rally as “crazy far-right wingers,” while Health Minister Pavlos Polakis called the demonstrators “junta nostalgists.” Deputy Minister of Agricultural Development Yiannis Tsironis characterized the rally as “relatively small” and with “no impact” on ongoing negotiations.

Such statements should not come as a surprise. In its pre-government days, numerous members of SYRIZA openly referred to Greece’s northern neighbor as “Macedonia.”

ERT journalist Stelios Nikitopoulos, one of the most prominent figures of the ERT protests, tweeted an invitation to a counter-rally against “nationalism.” Ironically, alongside his many postings decrying the protests as “fascism,” he also tweeted, unquestioningly, the police’s official figure of 90,000 attendees, comparing that figure to the one million said to have attended the 1992 demonstration. In reality, though, aerial photographs of the two rallies show a crowd that is similar to or perhaps even bigger in size this year.

Going one step further, ERT and national privately-owned broadcaster Alpha TV, in their reports on the rally, claimed that it was attended by merely “dozens” of protesters. ERT later claimed this was a “mistake.”

Foreign media aso got into the act. The Washington Post, quick to accuse others (including MintPress News) of serving up “fake news,” vaguely reported that “tens of thousands” attended Sunday’s rally, claiming it did not reach the magnitude of the 1992 rally. The French wire service Agence France Presse (AFP) also largely downplayed the scale of Sunday’s rally, especially compared to 1992, estimating turnout at “over 50,000,” while referring to the aforementioned Alco poll showing a majority in Greece favoring a “compromise,” but excluding other surveys contradicting this result.

AFP also tweeted a map of what it claimed to be the Greek province of Macedonia, which excluded the entire western section of the province but did include the separate province of Thrace, itself the occasional target of expansionist claims from Turkey. Despite corrections being sent or tweeted to AFP from numerous members of the public, the incorrect map remains online.

La Macédoine est reconnue sous ce nom par des pays comme les Etats-Unis, la Chine, la Russie, ou le Royaume-Uni. Mais pas par la plupart des pays européens, notamment la Grèce, la France et l’Allemagne, où elle est officiellement désignée comme “ARYM” #AFP pic.twitter.com/hmrquQBrN7

— Agence France-Presse (@afpfr) January 21, 2018

While, in all, the rally was peaceful and did not get broken up by provocateurs — as is often the case with rallies held in Athens, and particularly outside the Greek parliament — unfortunate incidents did occur. Provocateurs said to be representing far-right groups torched an anarchist squat in Thessaloniki prior to the rally, with no injuries reported. Another group, reportedly anarchists, attacked a bus delivering attendees to the rally, injuring one woman, while another similar group is said to have attacked a bus in Athens that was headed to the rally. A cyclist with Greek flags is also said to have been targeted by alleged anarchists in Thessaloniki prior to the rally. Leading up to the rally, graffiti was sprayed on Thessaloniki’s historic White Tower stating “You are not born Greek, you devolve into one.”

Momentum going forward — looking to February 4 in Athens

Despite all such challenges, turnout at Sunday’s rally was healthy and likely exceeded everyone’s expectations, and particularly those of the government, which now finds itself in a difficult position vis-à-vis the public. Despite its positive economic rhetoric, SYRIZA remains behind in the polls, while the Macedonia rally could be seen to have acted as an informal referendum against the government’s handling of the issue and its apparent willingness to accept what would be viewed as a soft compromise.

Adding to the government’s troubles, the rally’s organizers are now planning a follow-up demonstration, this time to be held in Athens, on February 4. At Sunday’s demonstration, it has been reported that speakers called for the Athens rally to be about more than just the name dispute, but other issues as well, including the government’s recently-passed omnibus bill which projects still further cuts and a new round of privatizations.

Furthermore, SYRIZA’s governing coalition partner, the populist-right Independent Greeks, perhaps seeking to salvage their own tarnished image, have proposed a referendum on the Macedonia issue, a position which is not shared by SYRIZA. This could potentially fracture the fragile coalition, perhaps leading to its collapse and the loss of the government’s parliamentary majority.

Many Greeks are also tired of their country being continuously threatened by its neighbors. At times, Turkish President Tayyip Erdoğan has made expansionist claims on the Greek region of Western Thrace, while Turkish Air Force jets routinely violate Greek airspace, including 141 such flyovers in one day last year. These are not victimless incidents. In 2006, Konstantinos Iliakis, a Greek air force pilot who was attempting to intercept Turkish fighter jets, died in an accident in the Southern Aegean Sea.

Problems also exist with northwestern neighbor Albania, which in 2016 dredged up a decades-old minority-rights issue of the Cham people in Greece, an issue unrecognized by both the UN and the OSCE. Last year, Albanian authorities in the city of Himara expropriated and demolished homes belonging to the city’s Greek minority.

There is also the unresolved Turkish occupation of almost 40 percent of Cyprus, which includes the division of the island’s capital, Nicosia. It’s ironic to hear Erdoğan lashing out at the U.S. decision to relocate its embassy in Israel to Jerusalem when his own military continues to divide the capital city of a sovereign country and EU member-state.

Also ironic are the recent words of Cypriot President Nikos Anastasiades, currently facing a battle for re-election, stating “the name doesn’t matter… [FYROM] can call itself ‘Northern Greece’ if it wishes.” Notably, the occupied northern territory of Cyprus is known as “North Cyprus,” and presently recognized only by Turkey. Anastasiades, in 2004, was a supporter of the United Nations’ “Annan Plan” for “reunification” of the island, which among other things would have maintained a Turkish military presence on the island, and which was rejected by Greek Cypriots in a referendum.

Many Greeks are therefore highly suspicious of the country’s neighbors, and even more so of the intentions of the United States, EU, and NATO and their ambitions in the region. It is feared by many that any compromise allowing FYROM to officially use the term “Macedonia” will simply fuel the expansionist claims of hard-line nationalists and politicians in FYROM, who might seek to “unify” Macedonia as one territory under one flag. Such concerns are not without merit. In June 2017 for instance, chants at a nationalist rally in Skopje claimed that “Thessaloniki is ours.” Such frustrations were channeled in Sunday’s rally in Thessaloniki. Similar claims are made by nationalist Bulgarians, some of whom, in a recent demonstration, accused Greece of “usurping” the name of Macedonia.

Greek authorities and the domestic and international media may choose to brand the protesters, or at least a significant percentage of them, as “fascists,” “nationalists,” “xenophobes” or any number of other epithets, in an attempt to delegitimize them and their concerns. But what is fascist about being leery of U.S. and NATO intentions in the Balkans or opposing the nationalist, expansionist ambitions of a neighboring state?

Symbolically, and in an indication that this is much more than a “far-right” issue, famed composer and cultural icon Mikis Theodorakis — who, despite a checkered political past, is viewed as an icon of the Greek left more broadly, and who is not noted for his fascist tendencies — issued an open letter addressed to the Greek prime minister. In this letter, Theodorakis warned that allowing the usage of the name Macedonia in any form by Greece’s northern neighbor would be “disastrous.”

Following up on this, Theodorakis stated after Sunday’s rally that “we have reached the unfortunate state where we have to apologize for our patriotism.” In previous open letters, Theodorakis has spoken out against the harshness of economic austerity and SYRIZA’s betrayal of its pre-election pledges.

Further illustrating that Sunday’s demonstration — and the belief that Greece should not compromise regarding the Macedonia name — is not an exclusively right-wing issue, is its endorsement by the left-wing Popular Unity political party. Popular Unity, which has positioned itself as an anti-austerity movement and which has also been active in the protests against home foreclosures and seizures, came out in support of the rally from an “alternative and radical perspective,” via its affiliated iskra.gr online portal. Popular Unity leader Panagiotis Lafazanis, in turn, described the rally as “expressing broader concerns” of society.

Theodorakis reflected the sentiment of many ordinary Greeks — who are neither fascists nor supporters of far-right parties, but who are fed up with a decade of economic crisis; with the loss of Greece’s sovereignty and control over the country’s own affairs; and with governments that have rescinded their promises and implemented endless reductions to salaries and pensions, increased taxes, slashed social services, sold off the country’s valuable public assets and utilities to foreign buyers at absurdly low prices, and who are seen as being both soft in negotiations on national issues and arrogantly indifferent towards the popular will. This disregard was evidenced when the SYRIZA-led government overturned the result of the July 2015 referendum that had rejected more EU- and IMF-proposed austerity, and was evident again both before and after Sunday’s rally.

Will the rally serve as a catalyst for broader developments in Greece? February 4, the day of the planned large-scale demonstration in Athens, may provide some answers.

Top Photo | Thousands of protesters take part in a rally against the use of the term “Macedonia” for the northern neighboring country’s name, at the northern Greek city of Thessaloniki, Jan. 21, 2018. Over 100,000 Greeks gathered in the northern city of Thessaloniki to demand that the term “Macedonia,” the name of the Greek province of which Thessaloniki is the capital, not be used by Greece’s northern neighbor known by the same name. (AP/Giannis Papanikos)

Michael Nevradakis is a PhD candidate in media studies at the University of Texas at Austin and a US Fulbright Scholar presently based in Athens, Greece. Michael is also an independent journalist and is the host of Dialogos Radio, a weekly radio program featuring interviews and coverage of current events in Greece.

<!–

–>

Source Article from https://www.mintpressnews.com/conflict-over-the-name-macedonia-part-of-larger-struggle-for-the-future-of-greece/236814/

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

January 30th, 2018

January 30th, 2018  Awake Goy

Awake Goy

Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: