In the earliest period of international trade in the Mediterranean region, the island of Cyprus was a surprisingly busy trading hub. Its exalted status during the Late Bronze Age (1,500 to 1,150 BC) was made possible by its huge supplies of pure Cyprus copper, which was mined in copious quantities near the ancient Cypriot village of Hala Sultan Tekke.

Archaeologists from the University of Gothenburg in Sweden confirmed Cyprus’s role in the Mediterranean’s first sophisticated international trade network during recent excavations at Hala Sultan Tekke , unearthing a dizzying variety of consumer items that could not have been mined or manufactured locally 3,500 years ago.

“We have found huge quantities of imported pottery in Hala Sultan Tekke, but also luxury goods made of gold, silver, ivory and semi-precious gemstones which show that the city’s production of copper was a trading commodity in high demand,” said excavation leader Peter Fischer in a University of Gothenburg press release announcing his team’s latest discoveries.

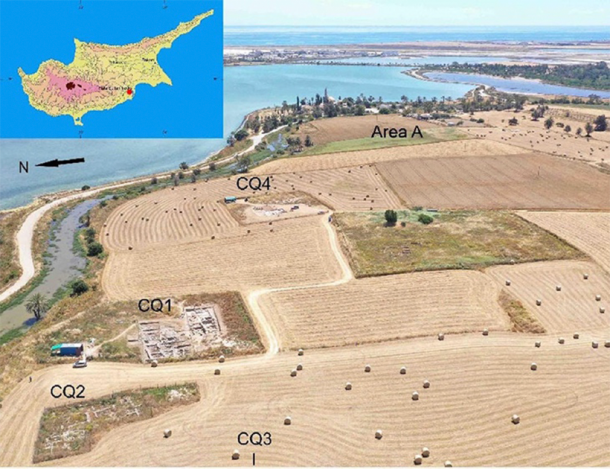

Drone image of Hala Sultan Tekke on the island of Crete with its excavated city quarters in the foreground, the harbor to the left and the Mediterranean Sea in the background. ( University of Gothenburg / CC BY 4.0)

A Thriving Cypriot City Built on Copper

Researchers from Sweden first began performing excavations on Cyprus in 1927, under the authority of the Swedish Cyprus Expedition. The most recent explorations on the island started in 2010 and have remained ongoing under Peter Fischer’s leadership (as an emeritus professor of archaeology, Fischer has been free to devote himself completely to this project).

The digs that produced the revealing cache of ancient luxury consumer goods took place near the modern city of Larnaca on Cyprus’s south seacoast, which is not far from the island’s immense copper deposits.

As Fischer explained in a paper just published in the Journal of Archaeological Science , the full development of the island’s copper mines starting around 1,500 BC transformed tiny Hala Sultan Tekke into a bustling and prosperous trading center.

“It is now clear that long-distance exchange, based on the large-scale intra-urban production and distribution of copper, involved regional and more distant suppliers of coveted goods, and resulted in the transition of the settlement from a late 17th century B.C. village to a trade hub with a minimum extent of 25 hectares [62 acres],” he wrote.

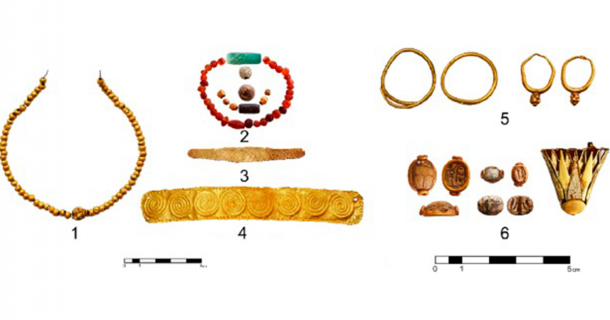

Imported goods from Sardinia (1), Italy (2), Crete (3), Greece (4), Türkiye (5), Israel (6), Egypt (7), Iraq (8), necklace with beads and a scarab (Ramesses II) from Egypt, Afghanistan and India (9) have all been found in Hala Sultan Tekke. ( University of Gothenburg / CC BY 4.0)

Excavating the Trade Hub on Cyprus

His team discovered that the city’s central or downtown area covered 14 hectares or 35 acres of ground, all of which was protected inside a thick perimeter wall. Excavations have found signs of human activity outside the wall as well, and this is the basis for Fischer’s estimate that the trading hub must have been at least 25 hectares or 62 acres in size in total (he believes it might have actually been twice this big, although further excavations will be needed to prove this).

While previous discoveries had produced evidence of some ancient international trade in Cyprus, this is the first study that has accurately measured the true scope of the island’s participation in Late Bronze Age exchange networks.

“Usually, settlements at this time and in this area covered only a few hectares,” he said, noting that Hala Sultan Tekke was likely no different in the beginning. But this once-small village was sitting on the proverbial gold mine—or in this case, a copper mine, which was so productive that its tons of output could have easily been traded for a vast amounts of gold (as some of it actually was).

Why Copper Was Worth its Weight in Gold in the Bronze Age

The Late Bronze Age (1,500 to 1,150 BC) spawned the Mediterranean region’s earliest international trading network. Following the most recent discoveries of the Swedish archaeologists, is clear that the copper deposits of Cyprus helped spur this sudden burst of exchange-based economic activity.

Throughout the Bronze Age, Cyprus was the largest producer of copper in the Mediterranean region. Pure copper could be alloyed with tin to make bronze, which could then be used to manufacture a broad variety of durable tools and weapons and attractive pieces of jewelry.

“Remains in the city show extensive copper production in the form of smelting furnaces, cast molds and slag,” Fischer said. “The ore from which the copper was extracted was brought into the city from mines in the nearby Troodos Mountains. The workshops produced a lot of soot and were placed in the north of the city so that the winds mainly from the south would blow the soot and the stench away from the city.”

People may have been unaware of it at the time, but copper smelting of this type produced dangerous quantities of toxins like arsenic, lead and cadmium. The people of Hala Sultan Tekke and the surrounding region may have developed illnesses as a result of their frequent exposure to such substances, but they may not have understood the true cause of these maladies.

But the value of copper and bronze on the international trading market wouldn’t have been a secret to anyone. Not only did the island have a lot of copper to mine, but its choice location in the eastern Mediterranean and its calm and well-protected southern harbor made it an easy place for early Mediterranean mariners and traders to find and visit.

Excavations on the island, including the latest one, have found valuable pottery, jewelry and luxury goods of all types brought by people’s living in what are now Greece, Turkey, Egypt and other Middle Eastern nations. Long-distance imports have also been unearthed, showing that traders arrived with goods to trade for copper and bronze from the lands of modern-day India, Afghanistan, Sardinia and the Baltic Sea region.

While its prize export was undoubtedly copper, Cyprus did also produce other goods that had value in trade. This included rare purple-dyed textiles and highly prized ceramic pottery that featured vividly painted images of plants, animals and people.

A selection of gold and stone jewelry excavated at Hala Sultan Tekke in Crete. ( University of Gothenburg / CC BY 4.0)

From Greatness to Collapse: The End of the Copper Empire

The Bronze Age “village-that-became-a-city” was not called Hala Sultan Tekke by its founders. This label was placed on it by the Swedish archaeologists, who named it after a mosque that sits near the excavation site.

Whatever its original name, discoveries at the site show that the settlement remained an active trading hub for nearly five centuries. But like so many other highly prosperous Bronze Age civilizations in the region, Hala Sultan Tekke experienced a sudden and shocking downturn in its fortunes sometime during the 12th century BC.

For a long time, the prevailing hypothesis has been that enigmatic invaders known as the Sea Peoples arrived in the eastern Mediterranean at this time and destroyed its cities and conquered its lands, until little was left of what had stood before. However, according to Peter Fischer this idea is too simplistic. What dethroned Cyprus from its status as an international trading center, he believes, involved a more complex interplay of natural and unnatural forces.

“There are now new interpretations of written sources from this period in Anatolia (modern-day Türkiye), Syria and Egypt, which tell of epidemics, famine, revolutions and acts of war by invading peoples,” he explained.

“In addition, our investigations indicate that a deterioration in the climate was a contributing factor. All of this may have had a domino effect, that people in search of better living conditions moved from the central Mediterranean towards the south-east, thus coming into conflict with the cultures in modern-day Greece, on Cyprus and in Egypt.”

Regardless of what ended Cyprus’s run as a major hub for international trade, the latest discoveries reveal that the island’s Bronze Age glory days were indeed more glorious than anyone could have imagined.

Top image: Copper slag excavated at Hala Sultan Tekke. Source: University of Gothenburg / CC BY 4.0

By Nathan Falde

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

March 18th, 2023

March 18th, 2023  Awake Goy

Awake Goy  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: