Last week an Israeli district court ruled against a Palestinian filmmaker and actor, Mohammad Bakri in a defamation and libel case, ordering him to pay hefty compensation to an officer in the Israeli military who was accused of carrying out war crimes in the 2002 documentary “Jenin, Jenin.”

On January 11 Bakri was ordered to pay Lt. Col. (res.) Nissim Magnagi $70,000 and the court seized 23 copies of the film and banned all future screenings.

The film captures Palestinians in the Jenin refugee camp in the northern West Bank during an Israeli military invasion at the peak of the second Intifada.

The case, as presented by Israeli media, dealt with defamation of character. Palestinians in the film describe an 11-day battle in the camp as the “Jenin massacre,” initially fearing hundreds had been killed in the invasion. Later human rights investigations revealed Israeli forces killed 52 Palestinians, of whom 22 were civilians, and demolished 300 of homes. The camp also sustained fire from helicopters. Twenty-three Israeli soldiers were killed during the fighting.

Human Rights Watch reported, civilians were killed in war crimes, but said there was no systematic massacre. That distinction was the basis for the lawsuit, even though Bakri was filming events as they unfolded and did not record a voiceover or add any external explanation.

To those familiar with the massive clash of narratives, the Israeli court verdict is not only political but historical and intellectual, as well.

Bakri, a native Palestinian born in the village of Bi’ina, near the Palestinian city of Akka, located in Israel, has been paraded repeatedly in Israeli courts and censured heavily in because he dared challenge the official discourse on the violent events which transpired in the Jenin refugee camp nearly two decades ago. In 2003 an Israeli judge dismissed an earlier defamation case where five Israeli soldiers who were not in the film, but claimed the presentation of the army in the documentary sullied their reputations, sought to sue Bakri.

Bakri’s documentary “Jenin, Jenin” is now officially banned in Israel. The film, which was produced only months after the conclusion of this particular episode of Israeli violence, did not make many claims of its own. It largely opened up a rare space for Palestinians to convey, in their own words, what had befallen their refugee camp when large units of the Israeli army, under the protection helicopters, pulverized much of the camp, killing scores and wounding hundreds.

To ban a film, regardless of how unacceptable it may seem from the viewpoint of the official authorities, is wholly inconsistent with any true definition of freedom of speech. But to ban “Jenin, Jenin,” to indict the Palestinian filmmaker and to financially compensate those accused of carrying out war crimes, is outrageous.

The background of the Israeli decision can be understood within two contexts: one, Israel’s regime of censorship aimed at silencing any criticism of the Israeli occupation and apartheid and, two, Israel’s fear of a truly independent Palestinian narrative.

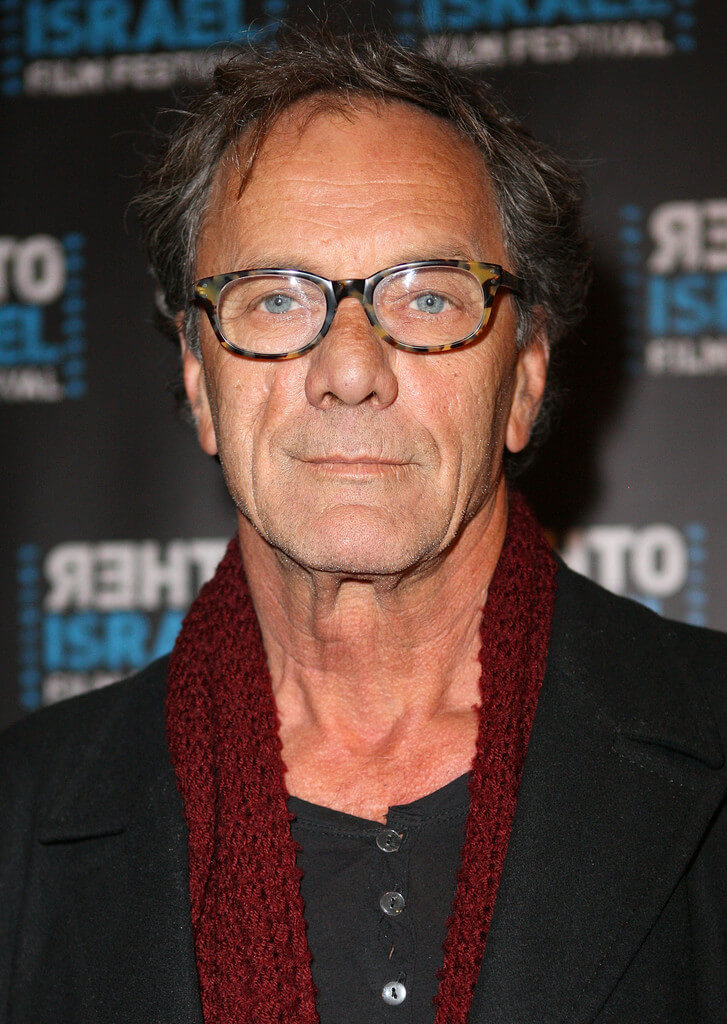

(Photo: Robin Marchant/Getty Images)

Israeli censorship dates back to the very inception of the state atop the ruins of the Palestinian homeland in 1948. The country’s founding fathers had painstakingly constructed a convenient story regarding the birth of Israel, almost entirely erasing Palestine and the Palestinians from their historical narrative. On this, late Palestinian intellectual, Edward Said, wrote in his essay, “Permission to Narrate,” “The Palestinian narrative has never been officially admitted to Israeli history, except as that of ‘non-Jews,’ whose inert presence in Palestine was a nuisance to be ignored or expelled.”

To ensure the erasure of the Palestinians from the official Israeli discourse, Israeli censorship has evolved to become one of the most elaborate and well-guarded schemes of its kind in the world. Its degree of sophistication and brutality has reached the extent that poets and artists can be tried in court and sentenced to prison for merely confronting Israel’s founding ideology, Zionism, or penning poems that may seem offensive to Israeli sensibilities. While Palestinians have borne the greatest brunt of the ever-vigilant Israeli censorship machine, some Israeli Jews, including human rights organizations, have also suffered the consequences.

But the case of “Jenin, Jenin” is not that of routine censorship. It is a statement, a message, against those who dare give voice to oppressed Palestinians, allowing them the opportunity to speak directly to the world. These Palestinians, in the eyes of Israel, are certainly the most dangerous, as they demolish the layered, elaborate, yet fallacious official Israeli discourse, regardless of the nature, place or timing of any contested event, starting with the catastrophe or Nakba of 1948.

Almost simultaneously with the release of “Jenin, Jenin,” my first book, “Searching Jenin: Eyewitness Accounts of the Israeli Invasion,” was published. The book, like the documentary, aimed to counterbalance official Israeli propaganda through honest, heart-rending accounts of the survivors of the refugee camp. While Israel had no jurisdiction to ban the book, pro-Israeli media and mainstream academics either ignored it completely or ferociously attacked it.

Admittedly, the Palestinian counter-narrative to the Israeli dominant narrative, whether on the “Jenin massacre” or the second Intifada, was humble, largely championed through individual efforts. Still, even such modest attempts at narrating a Palestinian version were considered dangerous, vehemently rejected as irresponsible, or sacrilegious.

Israel’s true power – but also Achilles’ heel – is its ability to design, construct and shield its own version of history, despite the fact that such history is hardly consistent with any reasonable definition of the truth. Within this modus operandi, even meager and unassuming counter-narratives are threatening, for they poke holes in an already baseless intellectual construct.

Bakri’s story of Jenin was not relentlessly attacked and eventually banned as a mere outcome of Israel’s prevailing censorship tactics, but because it dared blemish Israel’s diligently fabricated historical sequence, starting with a persecuted “people with no land” arriving at a supposed “land with no people,” where they “made the desert bloom.”

“Jenin, Jenin” is a microcosm of a people’s narrative that successfully shattered Israel’s well-funded propaganda, sending a message to Palestinians everywhere that even Israel’s falsification of history can be roundly defeated.

In her seminal book, “Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples,” Linda Tuhiwai Smith brilliantly examined the relationship between history and power, where she asserted that “history is mostly about power.”

“It is the story of the powerful and how they became powerful, and then how they use their power to keep them in positions in which they can continue to dominate others,” she wrote. It is precisely because Israel needs to maintain the current power structure that “Jenin, Jenin” and other Palestinian attempts at reclaiming history have to be censored, banned and punished.

Israel’s targeting of the Palestinian narrative is not a mere official contestation of the accuracy of facts or of some kind of Israeli fear that the ‘truth’ could lead to legal accountability. Israel hardly cares about facts and, thanks to Western support, it remains immune from international prosecution. Rather, it is about erasure; erasure of history, of a homeland, of a people.

A Palestinian people with a coherent, collective narrative will always exist no matter the geography, the physical hardship and the political circumstances. This is what Israel fears most.

Related posts:

Views: 0

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

January 23rd, 2021

January 23rd, 2021  Awake Goy

Awake Goy  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: