Hannibal Barca was a Carthaginian general who lived between the 3rd and 2nd centuries BC. He is perhaps best remembered for his military campaign against the Romans in the Second Punic War. Thanks to Hannibal’s capable leadership, the Carthaginians won several significant victories against the Romans, and succeeded in seizing parts of southern Italy.

The Carthaginians, however, were unable to score a decisive victory against the Romans. Moreover, the Romans changed their strategy in dealing with Hannibal, and eventually launched a counter-attack against Carthage, which led to their victory.

After the war, Hannibal remained an important leader in Carthage, but was later forced into exile by his enemies. He found refuge amongst Rome’s enemies in the east, though the Romans ultimately caught up with him. Instead of allowing himself to be taken to Rome as a prisoner, Hannibal committed suicide before he could be captured.

Hannibal and Hamilcar

Hannibal was born in 247 BC in North Africa. His name, which is “Hanba’al” in his native Punic, means “Mercy of Ba’al”, Ba’al being a major Punic deity. Hannibal was the eldest son of Hamilcar Barca , a Carthaginian general.

Carthaginian coin, likely depicting Hamilcar. On its reverse is a war elephant (Unknown Author / Public Domain )

At the time of Hannibal’s birth, Carthage was at war with the Roman Republic . This war, the First Punic War, ended with the defeat of Carthage in 241 BC. Hamilcar, however, never stopped seeing the Romans as his enemies, and launched a campaign to conquer the Iberian Peninsula . According to the Greek historian Polybius, whose Histories is a main source of information on Hannibal’s life, although not a direct attack on Rome this campaign was aimed at obtaining the resources needed to wage another war against the Roman Republic.

The Roman historian Livy’s History of Rome , another important work containing material on Hannibal’s life, relates a story about the Carthaginian general as a young boy. According to this story, whilst Hamilcar was offering sacrifices at the altar before embarking on his campaign, Hannibal, who was nine years old at the time, pestered his father to take him along to Iberia.

Therefore, Hamilcar took his son to the altar, placed the boy’s hand on the sacrificial victim, and told him to swear that “as soon as he possibly could he would show himself the enemy of Rome”. Hannibal did so, and left with his father for Iberia. In the nine years that followed, Hamilcar conducted a successful campaign in Iberia, which allowed Carthage to rebuild itself into a formidable power in the western Mediterranean once again.

Hamilcar was unable to fulfil his goal of waging a new war against Rome, as he died in 229 BC whilst he was still on campaign in Iberia. Hamilcar’s death, however, did not mean that the Carthaginian threat to Rome had disappeared, as the war that he so desired would be eventually be waged by his son.

Nevertheless, with the benefit of hindsight, Livy could point out that Hamilcar’s untimely death, in addition to the fact that Hannibal was still young at the time, caused the war to be delayed. Following Hamilcar’s death, the supreme command of the army and Carthage’s campaign passed into the hands of his son in law and Hannibal’s brother in law, Hasdrubal the Fair.

Hasdrubal the Diplomat

Unlike Hamilcar and Hannibal, Hasdrubal conducted the campaign in Iberia in quite a different manner. Instead of using military might to subdue the enemies of Carthage, Hasdrubal opted for diplomacy. According to Livy,

“Trusting to policy rather than to arms, he did more to extend the empire of Carthage by forming connections with the petty chieftains and winning over new tribes by making friends of their leading men than by force of arms or by war.”

Hannibal Barca (Youssefbensaad / CC BY-SA 4.0 )

Thanks to Hasdrubal’s diplomacy, Carthage was able to extend its control and influence into Iberia peacefully. In addition, Hasdrubal succeeded in negotiating a treaty with Rome, under which, the River Ebro was to form the boundary between Carthage and Rome in Iberia. Additionally, according to the treaty, Saguntum, which lay in between the territory of the Romans and Carthaginians, was to be a free city.

As Livy notes, however, “peace brought him no security”, and eventually Hasdrubal was assassinated in 221 BC. Livy’s account of Hasdrubal’s murder is as follows,

“A barbarian whose master he had put to death murdered him in broad daylight, and when seized by the bystanders he looked as happy as though he had escaped. Even when put to the torture, his delight at the success of his attempt mastered his pain and his face wore a smiling expression.”

Incidentally, Polybius paints quite different portrait of Hasdrubal, based on the account of a Roman storyteller by the name of Fabius. According to Fabius, Hasdrubal was an ambitious man, and had a lust for power. Having secured his position in Iberia, Hasdrubal returned to Carthage, with the intention of abolishing its constitution, and establishing a monarchy. The nobles, however, learned of Hasdrubal’s plans, and successfully opposed him. Therefore, Hasdrubal returned to Iberia, and continued to rule the conquered territories, without bothering too much about the politics back in Carthage.

Hannibal (247 – 181 BC) portrait on Tunisia 5 dinars (2013) banknote. Source: vkilikov / Adobe Stock

Hannibal Rising

In either case, it was during Hasdrubal’s governorship in Iberia that Hannibal was made an officer in the Carthaginian army. After Hasdrubal’s assassination, Hannibal, who was 26 years old at the time, was chosen by the Carthaginian armies in Iberia to be their supreme commander. Although Hannibal was now in a position where he could fulfil his oath to wage war against Rome, he knew that he needed to first consolidate Carthage’s position in Iberia, which his predecessors had been doing.

Like Hasdrubal, Hannibal employed diplomacy, and strengthened relations with the Iberians by marrying Imilce, a native princess. At the same time, Hannibal combined this diplomacy with the methods used by his father, and used military force to subdue other Iberian tribes.

In 219 BC, two years after coming to power, Hannibal was ready to take on the Roman Republic. Hannibal’s first attack, however, was not on the Romans themselves, but on the free city of Saguntum. The siege lasted eight months, during which Hannibal was wounded.

Saguntum (Diego Delso / CC BY-SA 4.0 )

The Romans, who counted Saguntum as an ally, regarded the Carthaginian attack on the independent city as an act of war. They did not, however, provide military aid to the besieged city. Instead, the Romans send envoys to Carthage to protest Hannibal’s action. When the city fell after eight months, the Roman envoys demanded Hannibal’s surrender.

The Second Punic War

When their demands were not met, Rome declared war on Carthage. Thus, the Second Punic War began in 218 BC. Since, on the Carthaginian side, the war was conducted primarily by Hannibal, the Second Punic War is sometimes referred to as the Hannibalic War.

Hannibal’s next move was to bring the war to the Romans by directly invading Italy. Having left his brother, another Hasdrubal, in charge of the defence of North Africa and Iberia, Hannibal assembled an army for the invasion of Italy. According to Polybius, this army consisted of about 90,000 infantry, 12,000 cavalry, and 37 elephants.

Since the Romans held control of the sea, Hannibal opted for a land invasion of Italy. This meant that the Carthaginian army had to cross overland about 1,600 km (1000 miles) to get from Iberia to Italy. In their way stood three formidable natural obstacles – the Pyrenees, the Rhone River, and the Alps. The last of these was the greatest, and Hannibal’s crossing of the Alps is remembered as one of the most celebrated military feats of the ancient world.

Conquering the Alps

First of all, crossing the Alps with an army was very difficult due to the harsh conditions on the mountains. This, however, was not the only challenge faced by Hannibal, as they also had to deal with hostile enemies. According to Polybius, whilst Hannibal and his army were traversing across the plains between the Rhone River and the Alps, a tribe known as the Allobroges, who inhabited that area, initially left them alone. When Hannibal began to ascent the Alps, however, they assembled an army, and occupied strategic positions on the route that the Carthaginians had to march through during their ascent.

Crossing the Alps ( Massimo Todaro / Adobe Stock)

The Allobroges intended to ambush Hannibal, and destroy his army in the Alps. Fortunately for the Carthaginians, they were forewarned of the Allobroges’s plan. Consequently, although the Allobroges inflicted heavy damage on the Carthaginians, they received more casualties themselves.

Polybius notes that the entire march took five months, 15 days of which were spent crossing the Alps. The historian also reports that by the time Hannibal had crossed the Alps, his army was reduced to about 20,000 infantry, and less than 6,000 cavalry.

Even though Hannibal had lost many men, he was still able to descend into Northern Italy and defeat the Roman force waiting for him on the plain to the west of the River Ticinus. In December 218 BC, about a month later, the Carthaginians again defeated the Roman army which met him on the west bank of the Trebia River. The Battle of the Trebia is considered as the first major battle of the Second Punic War, and was a grave defeat for the Romans. Hannibal’s victory at this battle convinced the local tribes of Gauls to join the Carthaginians in their war against Rome.

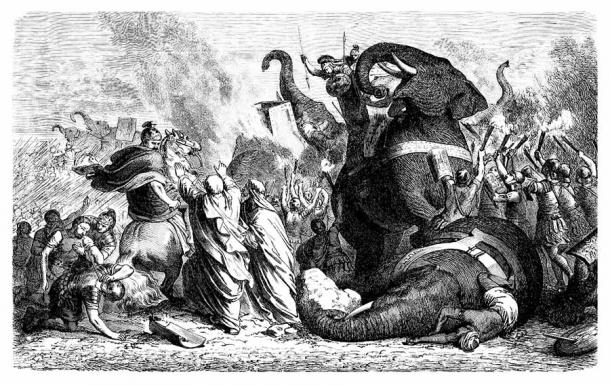

Hannibal’s Elephants ( Erica Guilane-Nachez / Adobe Stock)

The March on Rome

Hannibal continued his march southwards, and scored another victory at the Battle of Lake Trasimene in June 217 BC. Following this victory, however, Hannibal did not immediately march on Rome, either because he felt that his troops were too exhausted, or that Rome’s fortifications were too strong. Moreover, Hannibal was hoping that Rome’s Italic allies would defect to his side.

Therefore, in the summer of 217, Hannibal rested in Picenum, restricting his campaigns to local attacks against Apulia and Campania. But the Romans did not wait idly. Quintus Fabius Maximus Verrucosus was elected dictator after their defeat at the Battle of Lake Trasimene. The dictator avoided pitched battles, but harassed the Carthaginians continuously with the aim of wearing them down. This is now known as the “Fabian strategy”, and earned Fabius the nickname (initially as an insult) “Cunctator”, which translates as “Delayer”.

In the summer of 216 BC, Hannibal marched south again, and dealt an extremely costly defeat to the Romans at the Battle of Cannae . As well as leaving the forces of Rome shattered, this allowed Hannibal to gain a foothold in southern Italy, and caused many of Rome’s Italian allies to go over to the Carthaginians. Once again, however, rather than seizing the opportunity to march on Rome, Hannibal spent the winter of 216/5 BC in Capua, one of Rome’s former allies that defected to the Carthaginians.

The Battle of Cannae – the Romans are drawn into the center and destroyed (United States Military Academy / Public Domain )

This delay proved costly. In the next few years, the Carthaginians suffered severe hardships. Amongst other things, the Carthaginians were unable to score a decisive victory as the Romans avoided pitched battles at all cost. Hannibal’s numerical inferiority also made it difficult to for him to spread his forces across the peninsula and to hold the territorial gains made by the Carthaginians. Hannibal’s army was also slowly eroding, due to the death of his men, as well as the desertion of his Gallic allies, and reinforcements from Carthage did not materialize.

The Roman Counterattack

Whilst Hannibal’s army was being worn down in Italy, the Romans launched an attack on Iberia, and succeeded in expelling the Carthaginians from the peninsula. The leader of this campaign, Publius Cornelius Scipio , then invaded North Africa, which caused the Carthaginians to recall Hannibal from Italy in 203 BC.

The following year in 202 BC, Hannibal faced Scipio’s army at the Battle of Zama in North Africa, and was defeated by the Roman armies. Carthage sued for peace, and the Second Punic War came to an end in the following year. In honor of his victory at Zama, Scipio was awarded the title “Africanus”.

Scipio “Africanus” (Massimo Finizio / CC BY-SA 2.0)

Hannibal After The War

In spite of the threat that Hannibal had presented to Rome, he was not punished by the Romans after his defeat, and was allowed to continue serving as a leader in Carthage. Moreover, Scipio Africanus, who had defeated Hannibal at Zama, supported his leadership.

Hannibal, however, is said to have offended certain parts of the nobility, as he opposed their corrupt practices. Consequently, he was accused of inciting Antiochus III, the ruler of the Seleucid Empire in the Eastern Mediterranean, to wage war on Rome. Whilst some have questioned the soundness of this accusation, others have argued that Hannibal was hoping to start another war against Rome.

In any case, Hannibal fled to the Seleucid court. Following Antiochus’ defeat by the Romans, however, the victors demanded the surrender of Hannibal. Therefore, the former Carthaginian general fled further, and eventually ended up at the court of Prusias, the ruler of Bithynia, on the Black Sea.

Eventually, the Romans, whose influenced had increased greatly in the east, demanded that Prusias surrender his Carthaginian guest. Hannibal, realizing that the Bithynians were about to betray him, committed suicide by consuming poison. Hannibal probably died in 183 BC.

Hannibal was the greatest obstacle to Rome’s domination of the Mediterranean world. Following Hannibal’s death, there was no serious challenge to Roman supremacy for centuries. Hannibal’s invasion of Italy, especially his crossing of the Alps, is a feat that is as incredible today as it was when it happened. Hannibal himself continued to strike fear into the hearts of the citizens of ancient Rome long after his death, the latter captured perfectly in the Latin phrase used to describe a crisis: “ Hannibal ad portas” , or “Hannibal at the gates.”

Top image: Hannibal and his war elephants. Source: Lunstream / Adobe Stock

By Wu Mingren

References

Biography.com Editors, 2020. Hannibal. Available at: https://www.biography.com/military-figure/hannibal

Culican, W., 2020. Hannibal. Available at: https://www.britannica.com/biography/Hannibal-Carthaginian-general-247-183-BC

Gill, N. S., 2019. Overview of the Second Punic War of Rome. Available at: https://www.thoughtco.com/second-punic-war-120456

History.com Editors, 2018. Hannibal. Available at: https://www.history.com/topics/ancient-history/hannibal

Lendering, J., 2020. Hannibal Barca. Available at: https://www.britannica.com/biography/Hannibal-Carthaginian-general-247-183-BC

Livy, History of Rome, Roberts, W. M. (trans.), 1905. Livy’s History of Rome. Available at: http://mcadams.posc.mu.edu/txt/ah/Livy/index.html

Polybius, The Histories, Paton, W. R. (trans.), 1922-27. Polybius’ The Histories. Available at: http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Polybius/home.html

The Editors of Encyclopedia Britannica, 2014. Second Punic War. Available at: https://www.britannica.com/event/Second-Punic-War

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

June 13th, 2021

June 13th, 2021  Awake Goy

Awake Goy  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: