Every culture and society on Earth, both past and present, has their own ideas of what makes a person honorable or worthy. This is particularly true when it comes to warriors and their actions both on and off the battlefield, and concepts of Anglo-Saxon honor are no different. Codes of honor that dictate how warriors are to conduct themselves have existed for centuries, and some have been carried into modernity and popularized: the chivalric code of medieval knights, or Bushido of the Japanese samurai are perhaps the most well-known.

Before the chivalry of the Norman knights came to England however, a much older system of honor and loyalty had been in place for centuries, brought over by Germanic settlers from the Anglo-Saxon tribes. So what did the warrior code of the Anglo-Saxons look like, and how were their heroic predecessors different from the courtly knights who would come to take their place and eventually represent the notion of medieval warriorhood? Does the old world epic hero, the likes of Beowulf or Brythnoth, have any place in the modern world?

Anglo-Saxon Honor in the Heroic Age

The concept of honor was so pervasive in Anglo-Saxon society that it is impossible to pick up any piece of literature from the period without finding some mention of it. In fact, it is thanks to Anglo-Saxon literature – primarily epic poetry such as Beowulf, The Battle of Maldon and The Wanderer – that we have an understanding of how their warrior code and war culture looked, given the dearth of evidence from more “historical” sources from the period.

That is not to say that evidence of a non-literary nature does not exist – the Roman historian Tacitus wrote about Germanic warrior culture in his Germania around the turn of the 2nd century AD, revealing much about their notions of honor:

“When the battlefield is reached it is a reproach for a chief to be surpassed in prowess; a reproach for his retinue not to equal the prowess of its chief; but to have left the field and survived one’s chief, this means lifelong infamy and shame: to protect and defend him, to devote one’s own feats even to his glorification, this is the gist of their allegiance: the chief fights for victory, but the retainers for the chief.”

This passage from Tacitus captures the central tenets of the Germanic warrior code that are evident in later Anglo-Saxon literature: extreme courage in battle, concern for the reputation of oneself and one’s lord, honor and loyalty, and acquisition of glory. The pivotal factor underlying all these facets of the warrior’s code was of course the relationship between a warrior (or “thane”) and his lord. The Old English poem The Wanderer describes the importance of this relationship in the lamentations of a warrior who has lost his lord:

“Indeed, this he knows, who must long be deprived of the counsels of his beloved lord, when sorrow and sleep together often bind the wretched solitary one. It seems to him in his mind that he embraces and kisses his lord and lays hands and head on his knee, as he had previously, from time to time in days gone by, gained benefit from the throne.”

The poem also sheds light on the nature of the relationship between a lord and his loyal thanes, which was not that of master and servant but rather a reciprocal and mutually beneficial relationship. The communal obligation of the lord-retainer relationship was essential to the warrior’s way of life – to lack a lord is to lack place and role, friend and kin, help in need, and vengeance after death. The loyalty borne of friendship between the lord and his thane was the source of a warrior’s virtue – his courage, reputation and glory in service of his lord would define his personal honor in the eyes of his peers and society at large.

There was however, no direct word for “honor” in the Anglo-Saxon vocabulary, which would seem strange given it was such a crucial concept within their culture. The term for “loyalty” does not fully define the Anglo-Saxon concept of honor, nor can it be fully understood as the antithesis of “shame”. So how exactly did the Anglo-Saxons define honor?

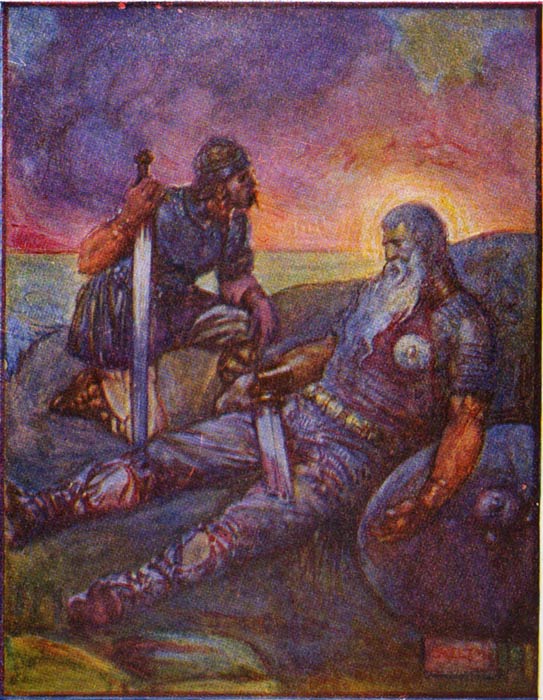

The story of Beowulf helps us to understand the Anglo-Saxon warrior code and war culture. ( Public domain )

Worth and weorð: Understanding Anglo-Saxon Honor and Gift-Giving

The word “honor” encompasses a system of values that signify a person’s “worth”, which in turn determines their value to society as a whole. For the Anglo-Saxons, a man’s value to society was dependent on his ability to take his place in the social order: to pledge unshakeable loyalty to his lord and in return for the lord to prove his value as a leader by rewarding loyal warriors with gifts and status. This transaction is what imbued a man with his “worth”, or weorð in Old English, and this was what constituted honor. The warrior class separated themselves from “ordinary” folk based on a sense of honor, defining themselves as the geweorðode or those “made worthy”.

The act of gift-giving was central to the Anglo-Saxon understanding of honor and the distribution of gifts in a public setting served as a physical enactment of the reciprocal bond of obligation between the lord and his thanes. An 11th-century book of Old English proverbs known as the Durham Proverbs gives us insight into how the gift-giving economy worked, with proverbs such as “each gift looks back over its shoulder” and “I give so that you give”. Anglo-Saxons did not give gifts without expecting a return, usually an oath of allegiance and military service.

The gift itself was also of great symbolic importance, as well as the act of giving. From studying Anglo-Saxon burial customs , historians have deduced that material objects were important symbols of status for both those belonging to the warrior class and those outside of it. For the warrior class, any valuable item given to them by their lord was seen to carry the worth of their lord’s favor, but weapons were particularly valuable items and bestowed great honor upon the recipient.

Weapons held enormous symbolic significance within Germanic tribal cultures. In fact, the Saxon tribal name is derived from the word seax, which is a type of short dagger every Saxon person carried with them. In fact, one could be honored by a weapon of great worth, either in possessing it or being marked by it.

In the well-known Old English poem Beowulf, a Frankish warrior killed by Beowulf is said to have worn breostweorðunge, which roughly translates to “adorned in breast armor.” The use of the word weorð implies that being killed by Beowulf’s weapon has bestowed honor upon him. Beowulf’s sword, known as Hrunting, is a weapon of great worth, given to him by the lord he serves, Hrothgar, and thus it holds great value and honor in its own right.

Anglo-Saxon warriors had their very own Anglo-Saxon honor code. ( Marla / Adobe Stock)

The Heroic Ethos Versus Christianity

The warrior code of the old-world Germanic cultures was immortalized in epic poems like Beowulf as a noble tradition of kinship, courage and glory. The conundrum of these poems, however, is the clash between the values of the heroic ethos with a newer Christianized worldview and value set. As the Anglo-Saxon Age in medieval England progressed and the kingdoms were steadily converted to Christianity, notions of honor and worth based on older, pagan traditions were less and less relevant.

As the famous medievalist J. R. R. Tolkien wrote of Beowulf: it encapsulates the blend between the “heathen, noble and hopeless” old days with the new Christian perspective that all men and their works shall die and only God is eternal. The converted Anglo-Saxon societies however, were not so ready to erase centuries of tradition that had been deeply ingrained in their culture from the time of their ancestors. Rather than abandoning long-held concepts of honor, they tried to adapt them to fit a new world molded by a new faith.

Some aspects of the old warrior’s code of honor were easily compatible with Christian ideologies. Both old-world and new-world philosophies agreed that life and honor are transitory things – as Beowulf exemplifies, “the days of men are fleeting” – and as such the warrior’s paramount goal was to seek immortality by making a reputation for himself through his deeds.

However, in a newly Christianized worldview the warrior would achieve immortality in a slightly different way than before, by performing heroic deeds not solely in the service of his lord but also in God’s service, and therefore earning admission to God’s eternal kingdom. These changing notions of immortality are also revealed in Beowulf, as the titular hero is encouraged to seek “eternal gains” and “God’s portion of honor” rather than worldly glory.

The emphasis in the heroic ethos on worldly success and material possessions was frowned on by Christian ideals, seen as an expression of avarice and pride, and the idea that material objects were what bestowed a man with weorð was modified so that the individual warrior himself was seen to be the holder of weorð. Honor was no longer solely a thing given to a warrior by his lord in the form of material gifts, it was now a thing that could be conferred on oneself by exemplifying devotion to God, and in this way a man was geweorðode or “made worthy”.

Medieval warrior. ( pixabay)

A Warrior Code for a New Age

There were parts of the old Germanic honor code that did not fit into the newly Christianized world however, and therein lay the struggle of the medieval Anglo-Saxon warrior which played out in the literature of the later Anglo-Saxon era. Most of the heroic poems – specifically Beowulf, The Wanderer , and The Battle of Maldon – read as elegies or lamentations rather than the epic tales of other Germanic or Norse cultures that glorify martial heroism as its own end. This is partly in recognition that the old ethos was passing into posterity and memory, as the heroic lifestyle and its social values was slowly lost. In the words of Tolkien, these poems tried to “preserve materials from a time already changing and passing using them for new purpose.”

Strangely enough, it is Tolkien himself who provided us with an image of what the heroic warrior code might have become, had it not been replaced with the chivalric code by the coming of the Normans. In his most famous work, The Lord of the Rings , Tolkien created a reflection of Anglo-Saxon culture in which the old codes of honor are repurposed so they can co-exist with Christian values in fictional harmony. The title itself, The Lord of the Rings , is taken from a phrase in Beowulf in Old English hringa-fengel (“lord of the rings”), symbolizing the old notion of exchanging honor for loyalty in the form of gifts and oaths.

In his fictional world of Middle Earth, Tolkien has adapted old world ideologies by removing the parts he deemed to be un-Christian and in doing so created a warrior’s code for the new world. The excesses of pride ( ofermod in Old English) shown by heroic characters like Beowulf often caused suffering for their loyal followers, such as Bryhtnoth did for his warriors in The Battle of Maldon . When the opposing army of Danes taunted Bryhtnoth and goaded him into allowing a “fair fight” by giving them safe passage across a treacherous river, it ultimately brought about the defeat of Bryhtnoth’s army and the death of those of his thanes who did not desert him. When recreating the same scenario in The Lord of the Rings , with Gandalf’s battle against the Balrog at the Bridge of Khazad-dûm, Tolkien has his hero sacrifice himself to save his loyal companions rather than give into selfishness or pride.

Similarly, Tolkien shows his condemnation of the obligatory service inherent in the act of gift-giving under old-world honor codes. Tolkien has been quoted as saying “one cannot attach conditions to a gift” and his attitudes towards Germanic gift-giving culture can be seen in his work. Tolkien adheres to a more Christian view of gift-giving as a selfless act, giving generously without the expectation of being repaid with service.

The villain of his story, Lord Sauron, is an exaggeration of the old system of exchanging gifts for loyalty, ensnaring his followers in obligatory service to him through the act of gifting them rings of power. The heroes of the story, however, demonstrate the Christian ethos of selflessness, humility, and egalitarianism. As Aragorn says to his loyal follower, Éomer: “Between us there can be no word of giving or taking, nor of reward; for we are brethren.”

Tolkien’s insightful take on Anglo-Saxon warrior culture and notions of honor shows how these old world ideologies are still relevant to a modern world. If the values and belief systems found in Anglo-Saxon literature are adapted and their excesses removed so as to fit modern ideologies, then the heroic world of Beowulf, Bryhtnoth, and their companions need not be relegated to the distant past to fall into obscurity. The system of honor and loyalty that the Anglo-Saxons lived by has just as much merit as the Anglo-Norman notions of chivalry that have survived into modernity, and Tolkien understood why these traditions still hold so much power today:

“[they are] written in a language that after many centuries has still essential kinship with our own, it was made in this land, and moves in our northern world beneath our northern sky, and for those who are native to that tongue and land, it must ever call with a profound appeal.”

Top image: Anglo-Saxon warriors lived by their Anglo-Saxon honor code. Source: warmtail / Adobe Stock

By Meagan Dickerson

References

Alonso, J. L. B. 2004. “’EOTHEOD’ Anglo-Saxons of the plains: Rohan as the Old English culture in JRR Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings.” Anuario de Investigación en Literatura Infantil y Juvenil 2.

Calcagno, J. 2021. “The value of weorð: A historical sociological analysis of honour in Anglo-Saxon society.” Journal of the Australian Early Medieval Association 17, no. 1.

Kundu, P. 2014. “The Anglo-Saxon War-Culture and The Lord of the Rings: Legacy and Reappraisal.” War, Literature and the Arts 26, no. 1 .

O’Keeffe, K. 1991. “Heroic values and Christian ethics.” In The Cambridge Companion to Old English Literature , ed. Malcolm Godden & Michael Lapidge, Cambridge University Press.

Porck, T. 2019. “Reshaping the Germanic Economy of Honour: Gift Giving in JRR Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings.” In Lembas Extra 2019: The World Tolkien Built , ed. Renée Vink, Unquendor.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

December 14th, 2021

December 14th, 2021  Awake Goy

Awake Goy  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: