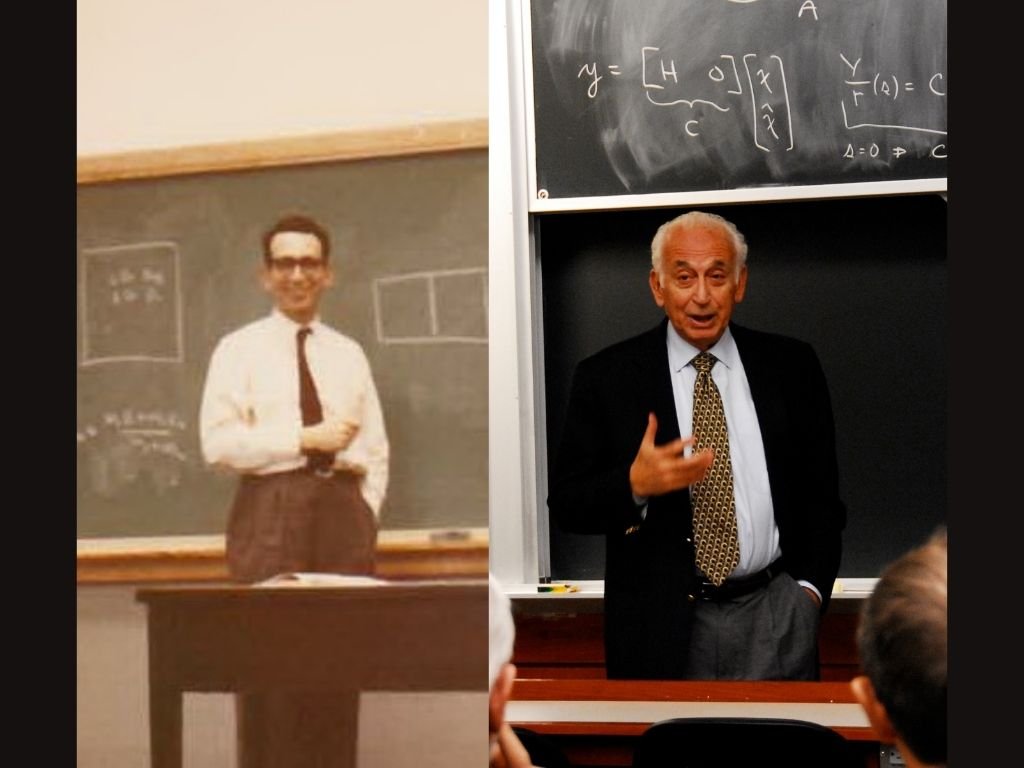

The life of the brilliant Greek-born inventor, entrepreneur and professor George Hatsopoulos was commemorated at an event held at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where he had served as a beloved teacher and mentor to generations of students.

Hatsopoulos, who was born Jan 7, 1927 in Athens, passed away on September 20, 2018 after a lifetime of solving problems that had stumped other researchers for decades — and in the meantime solving some problems that no one had most likely ever even thought of before.

“Being an entrepreneur is a bug,” he explained once to interviewers in an effort to explain the extraordinary motivation that governed his life. “It’s an affliction I always had throughout my life.”

But he didn’t have just the scintillating mind of a genius — his natural warmth and wisdom was beloved by generations of MIT students as well, making Hatsopoulos fondly remembered for his decades of teaching and mentoring students and colleagues.

The Greek native, who earned his PhD in 1949, was perhaps best known as an expert in the area of thermodynamics, an inventor, and the founder of Thermo Electron Corporation (now part of Thermo Fisher Scientific Corporation).

George Hatsopoulos: A brilliant businessman, scientist and philosopher

At the event hosted by MIT’s Department of Mechanical Engineering in January of 2020, Hatsopoulos’ former colleagues, friends, and family reflected on how much he meant to others as an educator, economist, mentor, role model, advisor, co-worker, and, as his colleagues stated, “his most cherished roles as husband and father.”

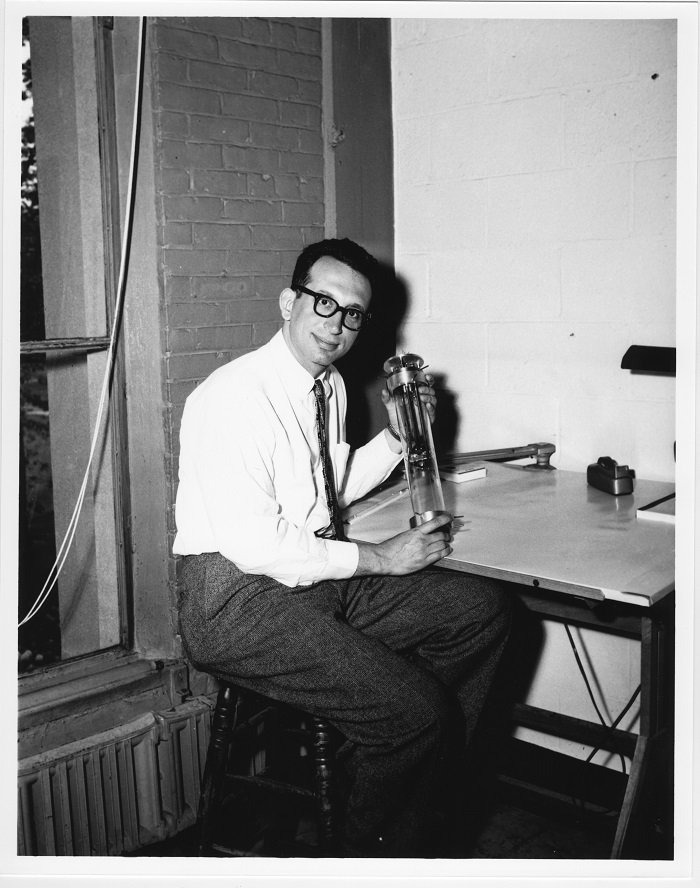

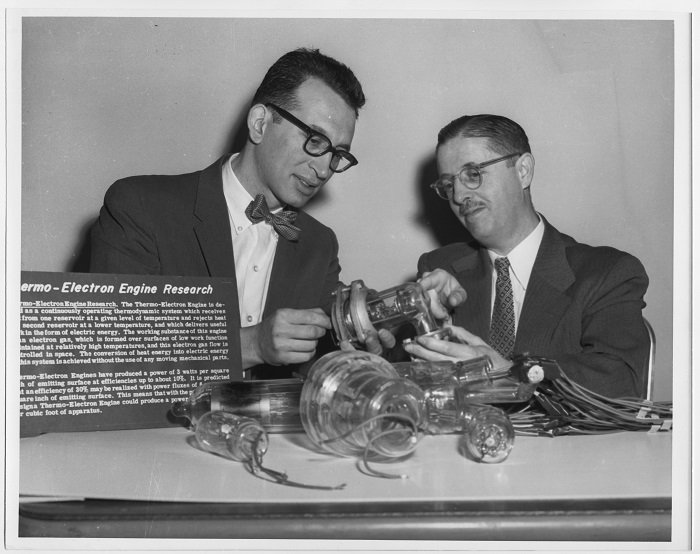

After writing his doctoral thesis, entitled “The Thermo-electron Engine”, Hatsopoulos went on to co-found the Thermo Electron Corporation in 1956; it became a global leader in analytical and monitoring instruments under his leadership.

“It was fun”

But he returned to the halls of academia because, as he himself explained simply, it was “fun,” and he remained a lecturer at the revered institution until 1990.

Nicho Hatsopoulos, the inventor’s son, spoke at the commemoration, saying “He was a businessman at heart who thought like a scientist and philosopher.”

His family life was everything to the brilliant entrepreneur, whose daughter Marina earned her master’s degree from MIT in 1993. Hatsopoulos’ wife Daphne was described as his “best friend and closest confidant” throughout all the years of their long marriage.

Walter Bornhorst, who was not only a colleague of Hatsopoulos but his son-in-law as well, recalled the man who came to loom so large in his life.

“George was my mentor,” he stated. “He shaped every aspect of my life, he taught me engineering, he taught me how to think, he taught me business and how to make money,” he explained. “But most importantly he provided me with my wife, Marina, the love of my life.”

As part of the event, the first-ever recipients of the George N. Hatsopoulos Faculty Fellowship in Interdisciplinary Research and the George N. Hatsopoulos Fellowship for graduate students spoke about how their research carries his legacy on into the future.

Graduate student Dionysios Sema, who himself is a native of the professor’s beloved Greece and the first recipient of the George N. Hatsopoulos Fellowship for Graduate Students, shared his work on advancing state-of-the-art predictive simulations of materials in extreme environments.

A life of stunning achievement

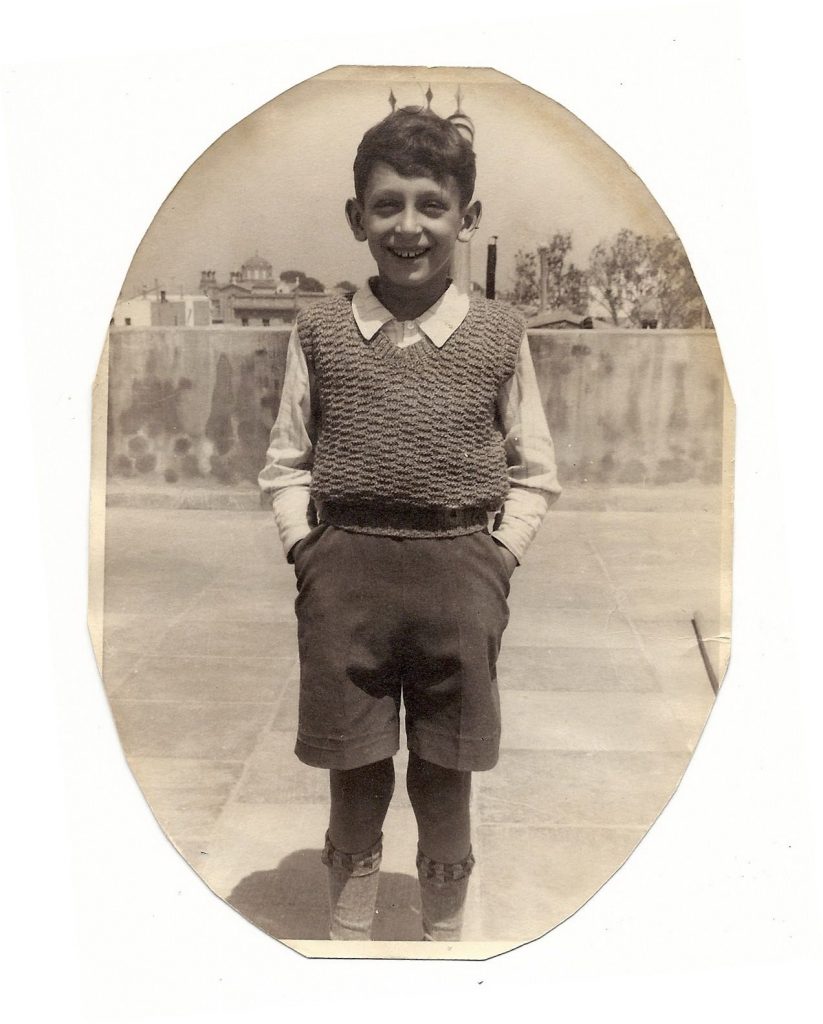

In an extraordinary video shown at the commemoration of his life, which shows what humans can achieve despite extreme privation, Hatsopoulos explains his origins and how his motivation took him from scurrying around piles of rubble in war-torn Athens in 1944 to the ivy-covered campus of MIT.

Hatsopoulos recalled that he basically spent the four years of the Nazi occupation of Greece “in the library in Athens, reading about Thomas Edison” — of all people, and subjects, to be learning about at that particular time.

“I might be the next Thomas Edison”

The budding engineer had a purpose, however, and it was linked to how his native brilliance had been noticed by his family members at a very young age. Hatsopoulos had only wanted, he said, to find out “Who is this guy Thomas Edison, that my uncles were saying that I ‘might be the next Thomas Edison’”?

“You have to understand that in Greece in 1942, there was tremendous hunger,” he explained as he tried to portray the desperation of those times. “There were people dead in the streets from hunger. There was also a lot of activity against the Nazis.

“I decided to do something that was very clearly punishable by death. There was a tremendous demand to hear news from the outside world. So I came up with the idea of building a shortwave radio to hear the BBC.

“The Germans were upstairs”

Hatsopoulos recounted that he would find the necessary vacuum tubes in junk piles and piles of rubble around the city and bring them back to his laboratory to work on them. “The Germans were upstairs,” he adds, as he gestures upward. “And that was my first enterprise. It was very dangerous — but it was very successful.

“You see, you shouldn’t lose sight of your purpose,” he admonished his listeners. “What is your purpose?

“I wanted to build a company that was at least as good as the company that Thomas Edison created.”

He had only, he said, to choose which country in which to fulfill his dream and where to write his all-important doctoral thesis. And just as importantly, where to do the groundwork to prepare for the creation of his company, which would be built on his own inventions.

Hatsopoulos then came up with the concept of converting heat into electricity by boiling off electrons. “For the first time,” he adds proudly, “MIT used its own money to support my thesis” and the revered Massachusetts institution therefore should be considered as the “co-founder of Thermo Electron.”

MIT, he added, “believed in serving society by finding ways to solve problems.”

Creation of artificial heart

One of the burning problems in American and Western society as a whole at the time — as it still is today — is heart disease. So of course Hatsopoulos directed his energies in that direction, determining next to create an artificial heart. “By the time I retired,” he recalled, “we had built 23 very successful companies.”

But the entrepreneur also devoted his life to teaching students — something that many questioned at the time, since he was also working so hard in his own companies. “But I like teaching, I really mean that,” he said.

“Focus on enjoying the ride”

“They paid me to teach at MIT, but every year I would donate that pay back to MIT. You learn a subject more by teaching it than by anything else — especially,” he added, “if you teach students that ask the most unheard-of questions that floor you. I didn’t do it because it was useful — I did it because it was fun,” he emphasized.

“That’s my goal — 80% fun,” Hatsopoulos adds. “And I’ve achieved it over time, many times.”

“It’s useful to set a certain direction you want to go.” However, he says, “After you set that direction, don’t focus on that goal — focus on enjoying the ride.”

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

August 7th, 2021

August 7th, 2021  Awake Goy

Awake Goy

Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: