The genetic connections between ancient horse populations living on opposite sides of the Pacific Ocean were more extensive than previously believed, new research has revealed. Past theories had emphasized their separate characteristics, but it seems the two horse populations were not as different as past studies had suggested.

That is the conclusion of an international team of researchers from seven countries, who performed a comprehensive genetic study of horse fossils recovered from various locations in North America and Eurasia (the continental area encompassing all of Europe and Asia). They have just introduced the results of their groundbreaking research in the journal Molecular Ecology , in an article published online on May 10.

“The results of this paper show that DNA flowed readily between Asia and North America during the ice ages, maintaining physical and evolutionary connectivity between horse populations across the Northern Hemisphere,” declared study co-author Beth Shapiro , a Professor of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology at the University of California-Santa Cruz.

Paleontologist Aisling Farrell holds a mummified frozen horse limb recovered from a placer gold mine in the Klondike goldfields in Yukon Territory, Canada. Ancient DNA recovered from horse fossils reveals gene flows between horse populations in North America and Eurasia. ( Government of Yukon )

Horse Populations and Migrations During the Ice Ages

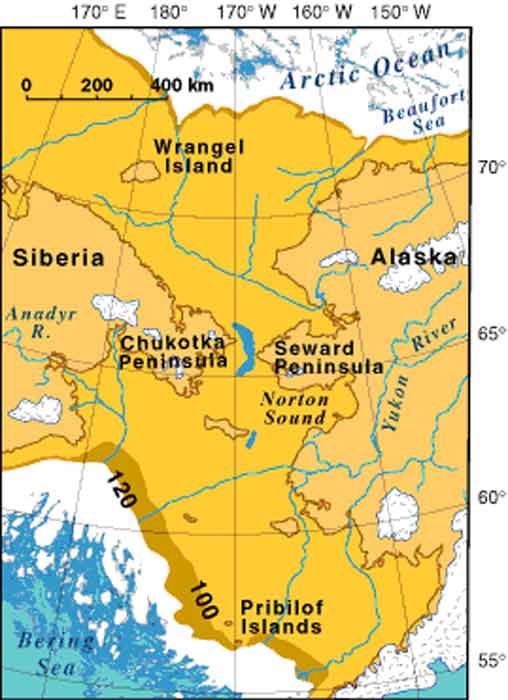

It is well known that the oldest horse species evolved on the North American continent, and later migrated to Eurasia moving westward during the Pleistocene Epoch (2.6 million BC to 9,000 BC). They were able to do so by crossing the Bering Land Bridge, which formed a direct connection between modern-day Alaska and Siberia . This stretch of land is now underwater but was exposed in the past during various Ice Ages, when sea levels were much lower than they are now.

Also known as Beringia, this land bridge was 620 miles or 1,000 kilometers wide at its peak. This provided plenty of space for migration from one continental land mass to the other, and even allowed for prolonged occupation by animals or earlier versions of modern humans.

Beringia was open during the last ice age, which lasted from approximately 125,000 BC to 9,000 BC. It was submerged by glacial melt after that and has remained beneath the ocean’s surface ever since. It was during the latter stages of the last Ice Age that the Asian ancestors of Native Americans completed their journey to their new homelands, crossing the land bridge in large groups before making their way southward.

But the Bering Land Bridge was also open during past ice ages, such as one that covered much of the planet’s land surface in ice one million years ago. It was during this time that the first migration of certain horse species from North America to Eurasia is believed to have occurred.

The equine species that crossed into northern Eurasia were from a lineage that ultimately produced the modern domestic horse . As this horse population spread far and wide across the Eurasian land mass, the animals that completed this long-distance trek followed their own unique evolutionary path. They diverged genetically from the horse species that remained behind in North America, which went extinct at the end of the last Ice Age. Domesticated horse populations were eventually reintroduced to North and South America from Europe, thus completing a cycle of migration that had begun thousands of years in the past.

The Wisconsin Glacial Episode, also called the Wisconsin glaciation, was the most recent glacial period of the North American ice sheet complex. The Wisconsin glaciation began approximately 75,000 years ago, which is likely when the “last” horse populations moved west from Alaska to Eurasia. ( Public domain )

Until now, evolutionary biologists didn´t think there was much more to the story than this.

“The usual view in the past was that horses differentiated into separate species as soon as they were in Asia,” explained Ross MacPhee, a paleontologist at the American Museum of Natural History and a co-author of the new research project. “But these results show there was continuity between the populations. They were able to interbreed freely, and we see the results of that in the genomes of fossils from either side of the divide.”

The team was able to determine this largely through their study of mitochondrial DNA , which is inherited exclusively from the mother. While it is not as rich as nuclear genetic material (inherited from both parents), mitochondrial DNA is much easier to find and recover from ancient, fossilized bones.

In this case, the researchers analyzed 78 newly recovered mitochondrial DNA samples, taken from ancient horse fossils found in different locations. They cross-referenced this information with mitochondrial data taken from 112 fossilized horse bones that had been recovered and analyzed previously.

Alisa Vershinina works in the Paleogenomics Lab at UC Santa Cruz where ancient DNA is extracted from fossils for sequencing and analysis. ( Paleogenomics Lab at UC Santa Cruz )

This type of genetic analysis is complex. But through careful analysis, they were able to create a detailed evolutionary tree establishing genetic relationships between individual horse populations across immense spans of time.

“We found Eurasian horse lineages here in North America and vice versa, suggesting cross-continental population movements,” explained the study’s lead author Alisa Vershinina, a genetic researcher affiliated with the UC-Santa Cruz Paleogenomics Laboratory. “With dated mitochondrial genomes, we can see when that shift in location happened.”

The researchers were able to track two separate migrations that brought the two horse populations in closer contact.

The first occurred not long after the original migration of horses to Eurasia, in the Middle Pleistocene period. The researchers conclude this migration occurred sometime between 875,000 and 625,000 years ago, likely in the next ice age after the one that allowed for the original migration. The direction of this movement was from east to west, as horses continued to cross Beringia from North America traveling into Eurasia. While some genetic divergence had obviously occurred by this time, it was not enough to prevent interbreeding, and additional fresh genetic material was added to the Eurasian horse DNA database at this time.

The second additional migration occurred in the Late Pleistocene, which precisely covers the last ice age (125,000 BC to 10,000 BC). The cooling and drying of the climate lowered sea levels and allowed the Bering Land Bridge to resurface. Taking advantage of the situation, groups of horses began moving back and forth between the interconnected land masses.

Interestingly, this time there was more movement from west to east than east to west. This mirrored the movement of modern humans from Asia to Beringia and on to North and South America. But the horse migrations were not in any way connected to human migrations, as the researchers estimate the former occurred tens of thousands of years earlier.

Notably, there was still not enough genetic divergence between species on either side of the continental divide to prevent interbreeding, even after so much time had passed since their original separation. It seems that the ancient horse populations of North America and Eurasia were not genetically distinct but remained as close variations on a unified evolutionary theme.

A World without Horses? Imagining the Unimaginable

As noted by study co-author Grant Zazula, a paleontologist employed by the government of Yukon in Canada, the disappearance of ancient horses in North America represented “a regional population loss rather than an extinction. We still don’t know why [it happened], but it tells us that conditions in North America were dramatically different at the end of the last Ice Age.”

“If horses hadn’t crossed over to Asia, we would have lost them all globally,” he noted, acknowledging the long-term ramifications of this fortunate population transfer.

If the Bering Land Bridge had never existed, there would be no horses left on the Earth today, or at any point in the recent past. Given the dramatic impact horses have had on the development of human culture over the centuries, this would have been a significant loss for humanity as well as for the planet.

Top image: Ancient horse populations crossed over the Bering Land Bridge in both directions between North America and Asia multiple times during the Pleistocene. Source: Julius Csotonyi / UC Santa Cruz

By Nathan Falde

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

May 22nd, 2021

May 22nd, 2021  Awake Goy

Awake Goy  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: