A deep and detailed analysis of Neanderthal DNA has revealed the existence of a distinct gene, called NOVA1, that would have significantly influenced early brain development in this long-extinct species. Laboratory tests on a Neanderthal ‘mini brain’ show that this gene produces changes in neural structure and activity that would have created dramatic divergence between the functioning of Neanderthal and Homo sapiens (modern human) brains.

A team of researchers affiliated with the UC San Diego School of Medicine believes this difference could be important. They think the presence of this gene, and its impact on brain development and functioning, could represent a primary point of separation between our Neanderthal cousins and ourselves. Neanderthals went extinct 40,000 years ago while Homo sapiens survived, and a closer study of NOVA1’s influence could help explain why this was the case.

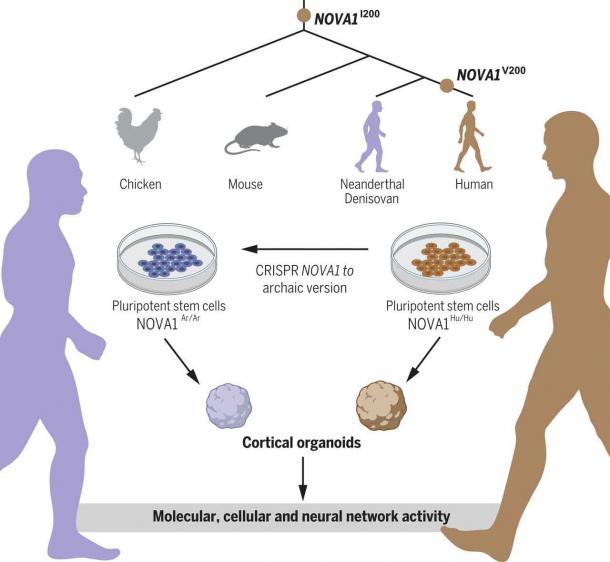

How the NOVA1 gene was used to create cortical organoids for the mini-brains used in the study. (Trujillo et al / Science)

Brain Development And The Neanderthal Mini-brain

The complete genome of the Neanderthal species was sequenced in 2013, from a phalanx (finger bone) Neanderthal fossil found in Siberia.

With this information in hand, the UC San Diego School of Medicine research team sought to isolate Neanderthal genes that were intimately involved in brain development processes. They eventually settled on NOVA1 as a candidate worth studying, and then set about designing an experiment that would prove their hypothesis that NOVA1 had a meaningful impact.

Using the characteristics of NOVA1’s genetic fingerprint as their guide, the researchers applied CRISPR gene-editing technology to malleable stem cells, in order to replicate Neanderthal brain cells in controlled laboratory conditions.

But this was only the first step in the replication process. The ultimate goal was to create a fully functioning Neanderthal “mini-brain” from these stem cells, in the form of a small cluster of brain cells that would to some extent mimic the structure and function of real brains.

This type of cluster is known as a brain organoid . Neuroscientists can induce them to assemble by sending the proper chemical signals to stem cells, which will then produce brain cells with the correct DNA identity and structural form. Brain organoids are grown in petri dishes , where their activities can be closely scrutinized and analyzed.

It must be stressed that these proto-organs do not function with anywhere near the level of complexity of a normal brain. They are tools that allow for more detailed study of brain development processes along with some simple forms of brain functioning, which cannot be fully understood through DNA analysis alone.

The research team involved in this project had previously used stem cells to create brain organoids of other primate species, including chimpanzees and bonobos. Their success in creating a miniature Neanderthal brain is truly groundbreaking. Since up to now it was not known if a functional brain organoid could be created from the recovered genetic material of an extinct species.

Neanderthals first appeared in the fossil record approximately 430,000 years ago, so what these scientists are studying in their petri dishes is offering them a glimpse of a past so remote that it is almost beyond imagination.

Petri dishes like these is where the mini-brain creation process gets started. (Muotri Lab / UC San Diego )

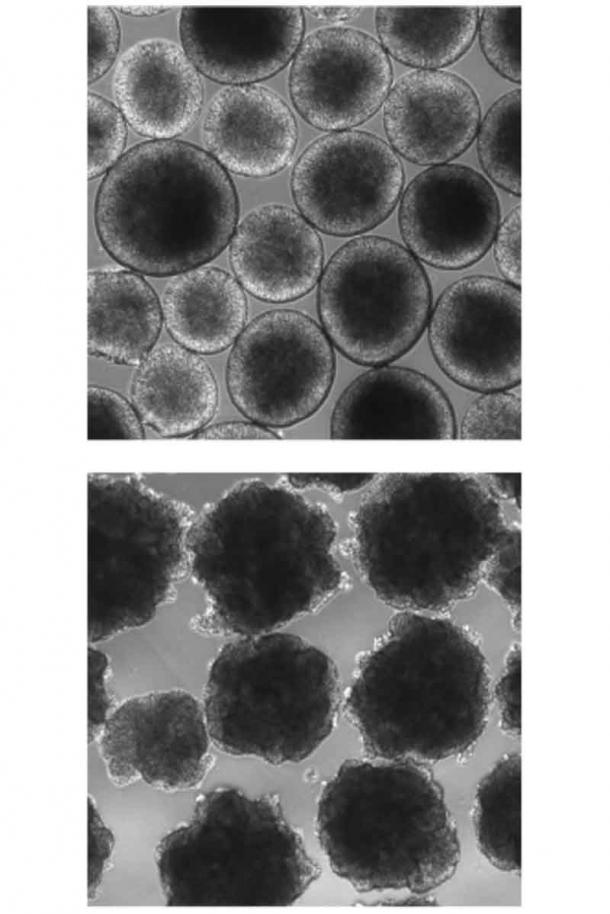

Examining the Neanderthal organoid more closely, the researchers discovered clear signs of bifurcation or division into two parts, in comparison to Homo sapiens organoids.

For starters, the shapes of the two mini-brains were different. Cellular division and procreation progressed differently in each type of organoid, as did the processes by which synaptic connections are created between neurons. The proteins involved in synapse formation were different, which helped create alterations in electrical impulse activity (it was higher in the early stages of brain development in Neanderthals).

Notably, the more intense electrical activity demonstrated in early-stage brain cells did not lead to the creation of synchronized neural networks in Neanderthal brain organoids, which is another point of separation with the Homo sapiens organoid.

None of this means that actual living Neanderthals were necessarily less intelligent than their human cousins. It simply means that their brains had a unique structure and functioned differently, which could have had implications for their capacity to thrive and survive in marginal environments or if occupying the same space as Homo sapiens (as they did, starting 60,000 years ago).

Cortical organoids carrying archaic NOVA1 (below) and modern NOVA1 (above) differ in shape and in neuron development. (Trujillo et al / Science)

Neurological Genetics And Survival Abilities In Both Species

While this research project focused on the activities of a specific Neanderthal gene, there is a twist in the story. From the standpoint of comparative evolutionary history, it is not the presence of Nova1 in Neanderthals that has the most dramatic implications. Rather, it is the gene’s lack of presence in modern human beings that matters the most.

Fossil and DNA evidence suggests that Homo sapiens and Neanderthals diverged from their common ancestral line sometime between 650,000 and 500,000 years ago. This divergence included various shifts in genetic make-up on both sides of the divide, which among other effects meant that either the NOVA1 gene developed in Neanderthals and not in humans, or persisted in Neanderthals and not in humans if it was already around before the divergence occurred.

“It’s fascinating to see that a single base-pair alteration in human DNA can change how the brain is wired,” said lead project researcher Alysson Muotri, a professor of Molecular and Cellular Medicine at University of California, San Diego. He asserts that his team’s study “could help explain some of our modern capabilities in social behavior, language, adaptation, creativity, and use of technology.”

In other words, divergences in brain functioning attributable to genetic differences could have given Homo sapiens a competitive edge, once the two species re-established contact 60,000 years ago. Such differences could have made them better hunters, better at self-defense and warfare, more capable of organized, cooperative behavior of various types, or more adept at surviving in extreme climatological conditions. Even small variations in such abilities could have led to the ultimate triumph of Homo sapiens over the Neanderthals, if in fact there was a competition over relatively scarce land and resources.

Comparison Homo sapiens (left) and Neanderthal (right) faces. (Daniela Hitzemann (left photograph), Stefan Scheer (right photograph) / unknown (reconstructions) / CC BY-SA 4.0 )

Your “Inner Neanderthal:” 1-4% Of Your Brain

While there are good theories to evaluate, we will never know for sure why the Neanderthals disappeared. But one thing we can say for sure is that the Neanderthals helped make us what we are, literally.

Despite no longer existing as a distinct species, the Neanderthals are still around, inside of us. Genetic research confirms that between one and four percent of the human genetic code was actually inherited from Neanderthals , through inter-breeding that occurred when the two species were living side-by-side.

It seems that the relationship between Homo sapiens and Neanderthals must have included a mixture of competition and cooperation. Overall, about 20 percent of the total Neanderthal genetic code still survives inside human chromosomes, providing us with a living connection to our rich, complex, and fascinating evolutionary history.

Top image: A comparison of modern human (left) and Neanderthal (right) skulls from the Cleveland Museum of Natural History Source: hairymuseummatt (original photo), DrMikeBaxter (derivative work) / CC BY-SA 2.0

By Nathan Falde

Related posts:

Views: 0

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

February 16th, 2021

February 16th, 2021  Awake Goy

Awake Goy  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: