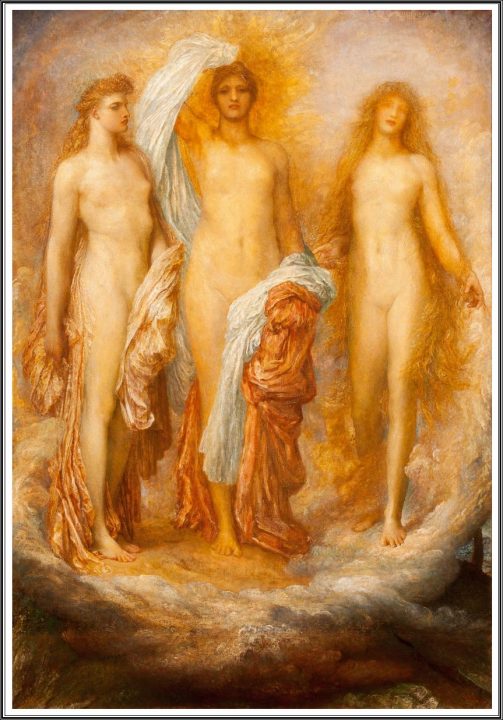

The Concise Oxford English Dictionary defines symbolism as “an artistic and poetic movement or style originating in the late 19th Century, using symbolic images and indirect suggestion to express mystical ideas, emotions, and states of mind”, this is precisely the first impression one gets when stumbling upon George Frederic Watts’ art for the first time.

George Frederic Watts (23 February 1817 – 1 July 1904) was a British painter and sculptor associated with the Symbolist movement in England. He once stated “I paint ideas, not things”. Many of Watts paintings were intended to form part of an epic cycle called the “House of Life”, in which, according to the artist himself, the emotions and aspirations of life would all be represented in a universal symbolic language.

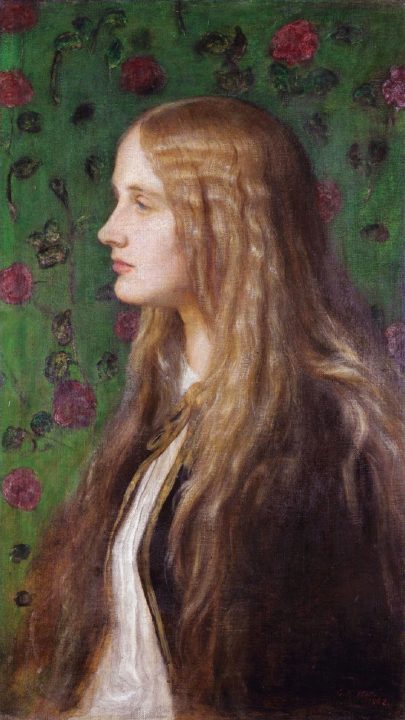

Of all artworks by Watts, which are quite a few since he was a prolific artist until the time of his passing, I could choose a handful which I count among my favourites by him. Among them I should mention one of his most popular works Hope (1886 version) but also Mrs Nassau Senior, Jane Elizabeth Hughes (1856), A Nymph (c.1860), Britomart (c.1877), Lady Margaret Beaumont and Her Daughter (1862) and most of all Dame (Alice) Ellen Terry (1864) a portrait of his young wife, the actress Ellen Terry, who was 30 years his junior when he married her on 20 February 1864. When she eloped with another man after less than a year of marriage, Watts was obliged to divorce her (I talk about this story in another article dedicated to British painter Albert Moore). There was once a time in which fine artists like Watts enjoyed such celebrity status that they were able to marry young beautiful actresses like the aforementioned one (even if it was only for a very brief period of time).

I would also like to mention two lesser-known works by Watts, one of them is Mammon (c.1884) (who seems to have a certain resemblance to Harvey Weinstein) and Industry and Greed (1900) which shows that Watts was pretty good at representing certain “archetypes”.

Biography

George Frederic Watts was born on his namesake George Frederic Handel’s birthday, in July of 1817, to a poor piano-maker and his wife. His delicate health and his mother’s illness led to him being homeschooled by his father. Taught about classic literature by a father with a conservative view of Christianity led him away from a life of conventional religiousness and into a career that was often influenced by The Illiad and many other classic works.

Early on in life, Watts showed artistic abilities. He learned sculpturing at age 10, in William Behnes’ studio, and devoted much of his time to studying the Elgin Marbles. By 18, he had enrolled in the Royal Academy as a student and began his career in portraiture. Another contemporary, Alexander Constantine Ionides, offered him support and encouragement and they eventually developed a close friendship.

Career

In 1843, Watts entered the public eye when he created a piece called Caractacus, which he entered into a design competition for the New Parliament Houses at Westminster. Despite winning the competition, Watts didn’t make many contributions to the decoration of Parliament Houses. Aside from the publicity that he gained from winning the mural design competition, he earned enough funds to go on a trip to Italy. While staying in Italy, Watts produced a number of landscapes inspired by work in the Scrovegni Chapel and Sistine Chapel.

Several years later, he returned to London intending to visit only briefly before moving on again. While back in London, he unsuccessfully tried to obtain his own building so that he could create a grand fresco inspired by his experiences in Italy. Instead, he settled for producing a 40ft by 45ft piece on the upper east wall in the Lincoln Inn’s Great Hall. The piece was titled Justice, a Hemicycle of Lawgivers and inspired by Raphael’s work.

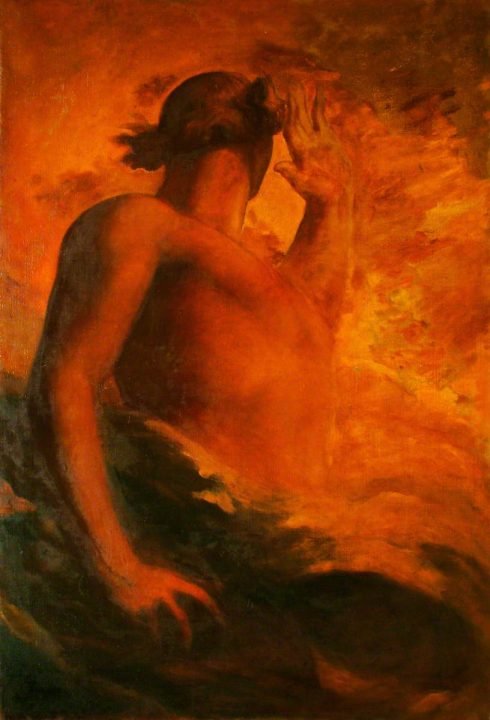

In some of his last paintings, Watts’ creative aspirations moved on from Michelangelo, Rossetti and other obvious influences into mystical imagery, as seen in The Sower of the Systems. In this piece, Watts appeared to anticipate the arrival of abstract art, as the painting depicts a Godlike entity as a shape that is barely visible amongst an energized star/nebulae pattern.

Throughout his life, Watts produced a vast number of portraits: Dante Gabriel Rossetti, George Meredith, Hannah Primrose and George Robinson are just some of the famous faces that had their portraits painted by Watts. Watts intended to create another cycle of paintings titled “The House of Fame” with such portraits.

‘Watts as an artist was fantastically famous in his day because he was considered to be more than a painter,’ explains Nicholas Tromans, curator of the Watts Gallery. ‘He offered this optimistic vision of what art could do. You can’t show that in a picture gallery, but a studio can communicate that engaging and participatory emotional involvement that Watts’ contemporaries talked about.’ – Excerpt taken from ‘Victorian artist George Frederic Watts’ studio opens to the public’ by The Spaces website

Later Life

In 1891, Watts bought some land south of Guildford, near Compton, in Surrey. The Watts Gallery, built near their home, was opened in 1904 shortly before Watts passed away. This art gallery, entirely dedicated to his life’s work, was the first museum of its kind, probably the only purpose-built museum in the whole of the UK that is dedicated to showcasing the work of just a single artist.

Watts continued to produce pieces of art until nearing the end of his life. His copy of The All-Pervading was precisely painted for the Watts Mortuary Chapel just 3 months before he died.

In his final years, George Frederic Watts turned his hand to creating sculptures. His most famous sculpture is the large-sized bronze statue named Physical Energy that was created in 1902. The statue depicts a naked horseman shading his eyes as he looked into the sun.

Sources: Totally History, The Eclectic Light Company, Understanding British Portraits, The Spaces, George Frederic Watts website, Watts Gallery website and wikipedia.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

March 19th, 2021

March 19th, 2021  Awake Goy

Awake Goy  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: