It was 1875 when 200 mysterious artifacts known as the Sinaia lead plates unexpectedly turned up at the Museum of Antiquities in Bucharest, Romania. They were all rectangular, apart from one, and ranged in size from 93 x 98 millimeters (3.66 x 3.86 inches) to 354 x 255 millimeters (13.94 x 10.04 inches). They were also adorned with strange inscriptions, which appeared to have borrowed words from a variety of European alphabets including ancient Greek, Latin and Cyrillic. In Greek a notable amount of military terminology had been adapted, including the words ‘basilero’ and ‘ chiliarcho’.

Discovery of the Sinaia Lead Plates

In addition, there were also several other unknown languages and archaic symbols that only added to scholarly confusion. Words such as ‘mato’ (king), ‘talipoko’ (fortress), and ‘kotopolo’ (priest) had no distinguishable characteristics from other European tongues.

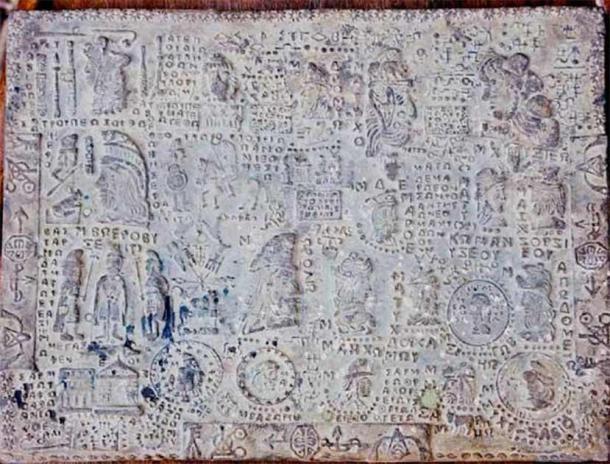

Within the linguistic patchwork were recognizable kings, toponyms, and hydronyms from the ancient kingdom of Dacia which seemed to correspond to the reign of King Burebista, a Dacian king contemporary with Julius Caesar of the Romans. Accompanying the writing were a broad collection of illustrations which depicted armies, fortresses, kings and their genealogical details, gods, temples, animals, religious emblems, buildings, as well as trophies.

Royal genealogy depicted on one of the Sinaia lead plates. ( Aurora Petan/Florin Croitoru )

The languages of the plates all seemed to have an Indo-European look, but there were no final consonants, inflections, or grammatical marks indicating gender, number, or tense. Even the words identified as feminine nouns all ended with -o, in contrast to Greek and Roman sources which traditionally used an -a.

Some scholars excitedly pointed to the plates as evidence for the ancient Dacian language, which until that point had been relatively unknown to linguists owing to the lack of Dacian written sources. A branch of the Indo-European family, Dacian had spread to the Carpathian Mountains in 2500 BC, and survived as a spoken language until 600 AD. But although much has been written about the Dacians by the Greeks and Romans, no manuscripts originating from Dacia have ever been found, with the little evidence that exists comprising of short phrases hastily scribbled down by Latin or Greek scholars. In fact, it was only in 1977 that scholars started to decipher it by using comparisons to other ancient people and places.

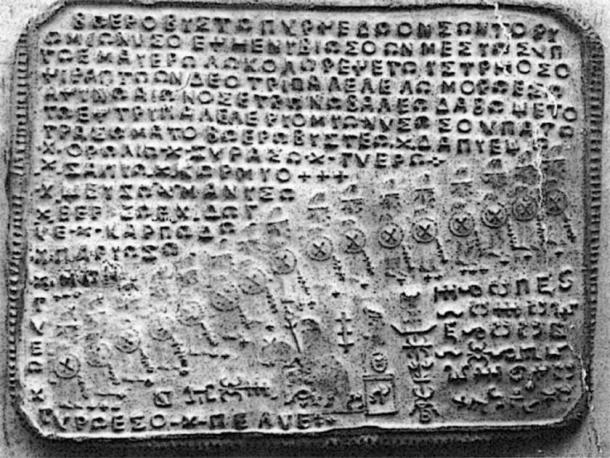

Inscriptions on a Sinaia lead plate. ( Vatra Stră-Rumînă )

The plates had been discovered by Bogdan Petriceicu-Hasdeu, a noted Romanian scholar and linguist who reportedly spoke 26 different languages and had been born into minor Moldovan nobility. Up until 1875, Hasdeu was well-known for his academic undertakings, having penned an ‘Archival History of Romania’ in 1863, the first such tome to use Slavonic and Romanian sources together, and a conspicuous book on Trajan’s Column as well as other histories and encyclopedias of Romania. Following a respected career, in 1876 he was appointed head of the State Archives of Bucharest where, by happenstance, he stumbled upon the Sinaia lead plates in a dusty old forgotten vault.

The authenticity of Hasdeu’s find, however, was questioned from its very discovery, with some accusing the esteemed academic of producing a forgery.

Burebista, the Dacians, and Julius Caesar

The Dacians inhabited modern-day Romania, and were founded by King Burebista II who reigned from 80 BC to 44 BC. According to Strabo, Burebista was a strong ruler:

“Arriving at the head of his people who was overwhelmed by frequent wars, Burebista got so excitedly through exercises, abstaining from the wine, and obedience to commandments, that in a few years he had built a strong state, and brought most of the Getae of the neighboring populations, even being feared by the Romans” .

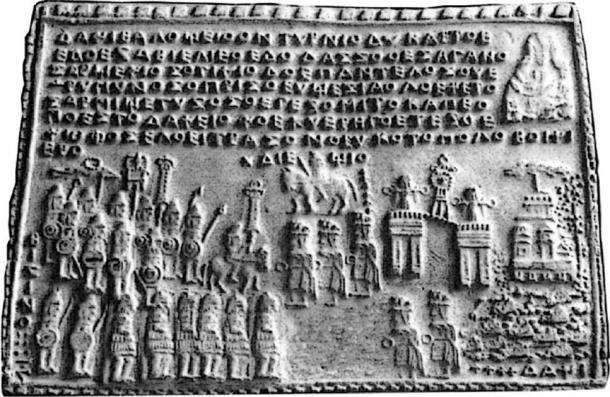

Dacian soldiers and roman prisoners received by priests at the gate of the Sarmizegetusa fortress. ( vatra-daciei.ro)

Indeed, under the guiding hand of Burebista, the Gets and the Dacians in time became a formidable empire. Celtic invasions and the threat of the Roman Republic helped the people to unify against external threats, a process that was initiated by Burebista’s offensive against the Scordis Celts in the Middle Danube area in 60 BC. Burebista’s army, said to be 200,000 strong, and including his own personal army as well as several other armies led by subordinate kings, utterly destroyed the Scordis Celts who were never mentioned in the ancient world again following their defeat.

The second phase of his unification plan was a campaign against Greek cities situated on the shores of the Euxin Point. Following a revolt against the Roman governor of Macedonia, Burebista pounced on the resulting void of authority, and in 55 BC was able to successfully pacify the Greek fortresses.

Relief depicting a fight between Romans and Dacians. ( radub85/ Adobe Stock)

At its full extent, Burebista’s empire stretched from Euxin Point to the East, Danubis to the West, the Haemus Mountains to the South, and the Marshes of Pripet to the North. With such an alarmingly huge empire, Burebista was marked as a potential Roman opponent. In particular, Julius Caesar, who observed a strategy of expansionism, despised the new kingdom, and made plans to invade the territory, sending 16 legions and 10,000 horsemen to the Roman province of Illyria in preparation. However, before he could start the conquest, the Roman general was famously assassinated by a group of his own Roman senators in 44 BC. In that year the same fate would also befall Burebista, who was murdered in a rebellion, leading to the division of Dacia into 4 separate kingdoms.

Are the Sinaia Lead Plates real?

The Sinaia lead plates contained some evidence that they were authentic, not a forgery.

A handful of the illustrations depicted details that closely matched later archaeological discoveries. In one of these images the outline of the Dacian capital of Sarmizegetusa, Burebista’s administrative and military center had been carved; it was later unearthed by archaeologists in the Orăştie Mountains in Romania’s Grădiștea Muncelului Natural Park.

Sarmizegetusa Regia, Romania. Dacian Fortress ruins. ( emperorcosar/ Adobe Stock)

Scholars were flabbergasted by the accuracy of the plates, which correctly portrayed the shape and size of Sarmizegetusa. In a similar turn of events, Burebista’s two-story limestone temple depicted on one of the plates shared remarkable precision with the very same ancient building discovered in 1956. Next, a Dacian medallion from 44 BC found in Burebista’s tomb during the 1940s was emblazoned with the same type of language found on the Sinaia Plates.

The plates themselves contained previously unknown details about the Dacians, including kings, queens, cities, and gods, that were not evident in any other sources. In relation to Hasdeu, the Greek symbols found on the plates contradicted a lot of his theories, suggesting, at least, that they weren’t artificially constructed to help Hasdeu’s academic career, as Hasdeu and his contemporaries had previously maintained that the Dacian alphabet was derived from old Hungarian. Indeed, one of the closest languages to Dacian was Phrygian, which commonly used the Greek alphabet.

However, the argument for a forgery appeared to be a lot more compelling as the composition and origin of the Sinaia lead plates began to be called into question.

Are the Sinaia Lead Plates Fake?

From the very beginning, the source of the Sinaia lead plates was shrouded in a thick veil of mystery and suspicion, as academics began to query their convenient ‘discovery’ in the warehouses of the Romanian State Archives by Hasdeu.

On closer inspection, the plates appeared to be newly crafted, with no signs of damage from age or corrosion, prompting many leading scholars of the day to immediately disavow the plates in the 1870s. A later study from the Institute of Nuclear Physics in Bucharest in 2004 would confirm that the plates had indeed been made from modern printing lead from the 2nd half of the 19th century.

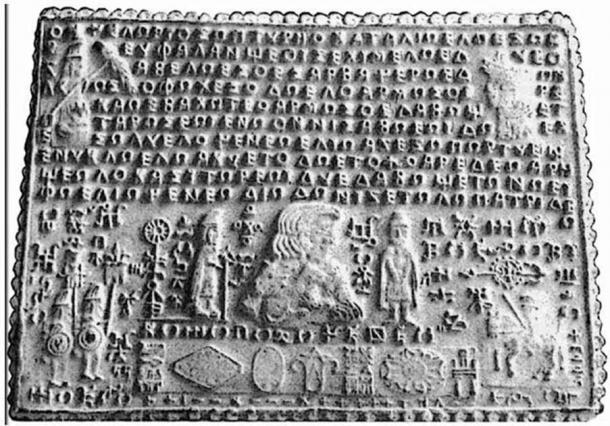

The plates were made from modern printing lead from the 2nd half of the 19th century. ( raus george michael )

The plates additionally had several mistakes, anachronisms, and curiosities which pointed to a falsification. One of the Greek cities, ‘Comidava’, which was mentioned by Ptolemy, was spelt incorrectly. In 1942, researchers discovered that the name of the city was actually spelt ‘Cumidava’, a fact that would have been known to a craftsman back in the first century BC.

Furthermore, one of the images featured the unusual addition of a cannon in the middle of a battle scene. The cannon had first been invented in China in the 12th century, appearing in Europe and the Islamic regions of the world in the 13th century, over a thousand years before the Dacians, rendering its inclusion incredibly suspect. Even stranger, a nearby flag on the same plate resembled a design similarly used by Stephen III of Moldavia or Stephen the Great, who ruled from 1457 to 1504. Other unusual phenomenon included the addition of Arabic glyphs as well as symbols that paralleled those found in secret masonic societies, suggesting the plates could also be a politically constructed fake.

The plates also displayed evidence that was favorable to some of Hasdeu’s theories. Hasdeu had long argued that the Dacian language was composed of words similar to modern Romanian and Slavic words, and that it had very little resemblance to the commonly agreed upon Dacian substratum, which was historically viewed as employing the Greek alphabet. Fittingly, the plates supported his trademark point of view that Romanian was derived from ancient Dacian and was not a Latin language.

One of the Sinaia lead plates. ( vatra-daciei.ro)

Perhaps the biggest giveaway was Hasdeu’s unwavering acceptance of the shaky origins story of the plates, which tried to explain away the newness of the ancient artifacts.

The Sinaia lead plates had apparently originally been found as a series of gold plates excavated during the construction of Peles Castle in 1875 for recently crowned Romanian monarch, Carol I. Upon discovery of the 200 plates, he decided to melt them down without translating the invaluable accounts of the people and ancestors of the Dacians which graced the golden surfaces, preferring the material to be used in the construction of his palace. The content of the plates was saved by a group of intrepid workmen, who, realizing their historical significance, copied them before they were melted at a nail factory in Sinaia.

Hasdeu fully believed the story, and in a later work from 1901 he argued that Albanian was also a language descended from Dacian, he would cite evidence from the plates as proof.

Forgotten Forgeries

Now, it is generally accepted by scholars that the Sinaia lead plates are a forgery, with the prime suspect being Hasdeu. Hasdeu not only found the plates but also continued to support the unsubstantiated claim that they were copies of original golden plates throughout his career.

Not only this, but Hasdeu had the expertise to pull such a forgery off. He was a brilliant and learned scholar, and with his encyclopedic knowledge of archaeology, linguistics, history, and ancient art, had the faculties and capability to fabricate what many consider an extremely impressive forgery.

Despite this, forgery allegations have never been conclusively proven, and it’s true that such golden tablets did exist in the area. Napoleon Săvescu, a Romanian historian of Dacia, found golden plates of similar design in Bulgaria. Yet, Săvescu shared similar traits to Hasdeu, propounding equally unrealistic theories of the Dacian language, including the claim that Romanians descended entirely from Dacian ancestors and not Roman colonists.

Due to the doubtful circumstances of their provenance, from the 1870s until the modern-day there has remained very little interest in the Sinaia lead plates as a source. It has never once been considered in the study of Dacian languages, and no serious research has ever been conducted on them. In 1916, the plates were not even considered significant enough to be saved with the rest of the Romanian Treasure to Russia during the First World War. Today, only 35 out of the 200 plates exist, with the majority either lost or deteriorated.

Top Image: One of the Sinaia lead plates. Source: Vatra Stră-Rumînă

By Jake Leigh-Howarth

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

April 3rd, 2022

April 3rd, 2022  Awake Goy

Awake Goy  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: