A tzompantli was a wooden rack developed by several Mesoamerican civilizations to publicly display the skulls of war captives. According to Joel W. Palka’s 2007 book Historical Dictionary of Mesoamerica, the tzompantli was a scaffold-like construction of poles on which heads and skulls were placed, and many similar skull towers have been discovered across Mesoamerica dating between 600–1250 AD.

In 2017 researchers discovered 650 skulls at a huey tzompantli (skull rack) which measures approximately five meters (16.4 ft.) in diameter. This morbid architectural feature is situated beneath the Templo Mayor at the ancient Aztec capital, Tenochtitlan, below modern day Mexico City. According to The BBC , the National Institute of Anthropology and History ( INAH) have announced that the same team have now uncovered the facade and eastern side of the tower, and “119 human skulls of men, women and children.”

Section of the huey tzompantli (skull rack) found under Mexico City. ( INAH)

Tzompantli: Gifts for the Gods Or the Gods Themselves?

Reuters in Mexico City say this deathly feature was still active in the 1400s and that the “huge array of skulls” must have struck fear into the Spanish conquistadors when they captured the city under Hernán Cortés in 1521 AD. The Mexican Minister for culture, Alejandra Frausto, said in a INAH statement that the discovery of the huey tzompantli “is without doubt one of the most impressive archaeological finds of recent years in our country.” The minister also confirmed that Mexican archaeologists have now identified three separate construction phases at the tower, which was erected between 1486 and 1502 AD.

When this skull tower was first discovered in 2017 it came as something of a shock to Mexican anthropologists. Normally, the skulls of young male warriors were built into these skull racks, but in this instance they also unearthed the crania of women and children, suggesting researchers have for a long time misinterpreted human sacrifice in the Aztec Empire. In a Telegraph article, archaeologist Raúl Barrera says, “Although we can’t say how many of these individuals were warriors, perhaps some were captives destined for sacrificial ceremonies.” Furthermore, Barrera added that while researchers don’t currently know why all these women and children “were all made sacred,” maybe they were “turned into gifts for the gods or even personifications of deities themselves.”

The archaeologists found the crania of men, women, and children in the tower of skulls. ( INAH)

Human Sacrifice: The Ultimate Tool of Social Control

The Aztec priesthood were a bloodthirsty lot who used to grab folk from the streets at their whim, from any social class, to service the gods. Generally captive warriors were laid on their backs on sacrificial stones and the priests used razor-sharp obsidian blades to cut through their abdomens before opening their chests and offering their still-beating hearts to the wanton war god Huitzilopochtli. According to an article on History.com, when the life had drained from the sacrificial victims , their lifeless bodies were tossed down the steps of the towering Templo Mayor, and the heart, still beating, was held towards the sky to honor the god.

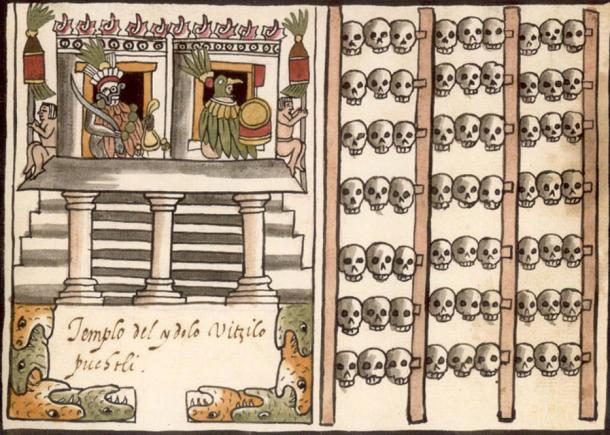

1587 illustration from the Codex Tovar. Left: A temple or pyramid surmounted by the images of two gods flanked by native Mexicans. Right: A tzompantli (Aztec skull rack). ( Public Domain )

While history generally records the arrival of the Spaniards in Central America as the beginning of the end for the Aztecs, it can be argued that they were already on the way out. Practices like human sacrifice destabilized their social strata and lodged distrust in the priesthood and noble classes. It is known that the Aztec state sponsored ritual practice ended about 10 years preceding the arrival of the Spaniards, but this rack of women and children skulls reopens these assumptions in several ways.

Warriors, Women, and Children – All the Same to Blade Wielding Aztec Priests

Not only does the huey tzompantli discovery challenge the accepted dates for when sacrifice ended in the Aztec Empire, but it also brings into question who was being slaughtered, and why. It is doubtful the women and children discovered in the Mexico City skull rack were sacrificed to the God of War, so perhaps they were added to the feature in response to the arrival of the devils from the east. Maybe this death tower was a fearsome reminder that the Biblical God of the conquistadors had no place in the shadowlands of the Americas, where not even women or children could escape being sacrificed to the pantheon.

Top Image: Detail of skulls on the tzompantli (skull rack) found under Mexico City. Source: INAH

By Ashley Cowie

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

December 13th, 2020

December 13th, 2020  Awake Goy

Awake Goy  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: