When Julie Mayer was growing up in downtown Brooklyn, artist and Holocaust survivor Fred Terna was her parents’ friend, “the old man with the funny accent” often seated at their Passover Seder table with his family.

“He was the old person who was in my sphere,” said Mayer, 31, who would see him most weeks at the Kane Street Synagogue. “I would see him at kiddush and he’d ask me about school.”

Now, Mayer, director of philanthropy at Year Up Greater Boston, a nonprofit that provides workforce development training for young adults, has written “Paint and Resilience, The Life and Art of Fred Terna” (November 2020, JBJ Vision), a biography that tells Terna’s remarkable story of survival, along with reproductions of more than two dozen of Terna’s works photographed by his son Daniel Terna.

The book is based on some 60 hours of conversations between Terna and Mayer, who, though she wrote a young adult novel in 2011, doesn’t see herself as a writer.

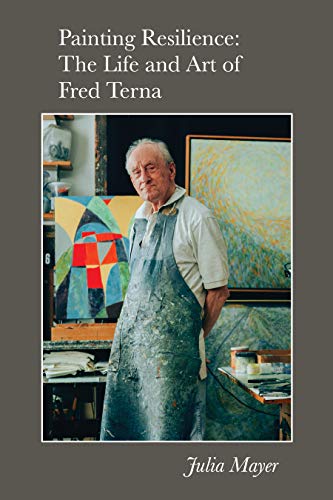

Artist Fred Terna on the cover of ‘Painting Resilience: The Life and Art of Fred Terna,’ written by Julia Mayer (Courtesy Daniel Terna)

In the same vein, said Mayer, “I call myself a ‘Fred expert,’ not a Holocaust expert.”

“Painting Resilience: The Life and Art of Fred Terna” weaves together the intense and sometimes bleak messages of his contemporary artworks with his life story. He began sketching as a 16-year-old inmate in Terezin, signing his sketches of crowded bunk beds and railroad tracks with a symbol rather than his name.

As Terna has said many times, drawing was a reminder of his humanity.

The book was launched on November 16, and Terna and Mayer will be holding online conversations about the book. All proceeds from sales will be donated to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, holder of the largest collection of Terna’s work.

Some six years after embarking on this project, Mayer still can’t say what drew her to ask for the studio tour that Terna had often suggested when she was younger.

“It took a long time for that acquaintanceship to flip,” said Mayer. “By high school I knew he was a survivor and that my parents had a few of his art pieces. I didn’t place him as someone who made living as an artist.”

When she was in her mid-20s, Mayer finally took him up on his offer and made a visit along with her brother and then-boyfriend. A studio visit with Terna usually takes about 25 minutes; Mayer’s lasted for three hours.

Terna’s art is also displayed throughout the Brooklyn home he shares with his second wife and adult son, and he calls the pieces that hang in the hallways “just storage,” said Mayer.

Overall, Terna’s work is extremely abstract and beautiful, said Mayer, and consistently represent all parts of his life story.

A work by artist and Holocaust survivor Fred Terna, included in Julia Mayer’s book ‘Painting Resilience: The Life and Art of Fred Terna’ (Courtesy Daniel Terna)

“When you look at the art with him, a pastel with lines, he would say, ‘This is what mass graves look like,’” said Mayer.

“We kept asking to see more,” she said of her first tour through Terna’s studio. “By the time I got home, I knew I wanted to write the book.”

Mayer was familiar with the broad strokes of Terna’s Holocaust history, having heard him speak about it at the Seder table and other holiday meals.

“Sometimes we would ask Fred if we could ask questions, and sometimes he would say, ‘Not tonight,’” recalled Mayer. “Sometimes he wouldn’t have specific memories, but it was a doorway into a conversation. It takes him much longer to recover from forays into his memory, so he knows that about himself.”

A work by artist and Holocaust survivor Fred Terna, included in Julia Mayer’s book recently written about him, ‘Painting Resilience: The Life and Art of Fred Terna’ (Courtesy Daniel Terna)

Mayer’s family had Holocaust history too. Her paternal grandfather was born in Germany and her maternal grandfather was a liberator at a concentration camp known as Ahlem. He spoke about it infrequently, but was so impacted by what he saw there that he recited Kaddish for the rest of his life — he lived until the age of 100 — for all those buried in a mass grave.

Terna, who was a Czech teen at the start of the war and survived four concentration camps, was interested in working with Mayer because he wanted his story to be told to the next generation.

While Terna is a frequent public speaker about his Holocaust experiences, he “has a certain way he tells it,” said Mayer, and she wanted to delve more deeply into those stories.

The two spent days together; Terna would speak and Mayer would ask questions. But when she sat down to write the book, she was faced with the conundrum of how to shape the complicated content.

Julia Mayer, 31, embarked on a six-year journey to write about artist and family friend Fred Terna, 97, a Holocaust survivor with a tremendous story (Courtesy Julia Mayer)

She knew she wanted to weave Terna’s art throughout, but found it difficult to find the right structure. The first draft of the book had a confusing timeline, and Mayer worked with a professional editor on the second draft, which included inserting herself into the story.

“People would tell me the story had to be about me and Fred,” said Mayer. “It opened the door for me to provide more context, to comment on things I noticed, like his lack of emotion,” said Mayer. “It became the story of me and Fred.”

Terna didn’t read the book until very recently, and refused to give Mayer notes about it.

“He said, ‘This is your artwork. I don’t want to give you notes on it just like you don’t put notes on mine,” said Mayer.

Once Terna read it, Mayer felt like a burden had been lifted from her shoulders.

“The only review I needed was his,” she said. “This was a project that I saw as ours; he saw it as mine.”

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

November 28th, 2020

November 28th, 2020  Awake Goy

Awake Goy  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: