In 2005, Elaine Solowey made history when she managed to germinate a 1,900-year-old date palm seed, bringing an ancient species back to life.

Now, the California-born Solowey has set her sights on rescuing dozens of other threatened or endangered types of plants, with hopes of rehabilitating habitats and finding ways to help farmers and others cope with a warming climate in an already arid region.

Revered by plant geeks like a rock star, Solowey, 68, works out of an office crammed with books, old coffee and spice jars filled with seeds, and little vials with different shapes of thorns. She also has two run-down greenhouses that lack even basic temperature control.

It is in this unlikely kingdom at the Arava Institute for Environmental Studies in southern Israel that she continues to produce more date palms, other plants mentioned in the Bible such as frankincense, myrrh and Balm of Gilead (associated with the caravan that made its way from Gilead to Egypt and to which the young Joseph was sold by his jealous brothers in Genesis 37:25), and yet more species that may hold medicinal potential or the promise of new crops that can be grown sustainably in dry conditions or that are valuable to the ecosystem and in danger of extinction.

Solowey, 68, immigrated to Israel from California in 1974 and has since spent her life on Kibbutz Ketura, which was founded by North American graduates of the Young Judea gap year program in 1973, 50 kilometers (31 miles) north of Eilat.

Arriving as a qualified tree surgeon, she went on to earn further degrees and a doctorate by correspondence with US universities. In 2016, she was awarded the Ben Gurion Prize for the Development of the Negev.

Dr Elaine Solowey in her office at Kibbutz Ketura in southern Israel, March 21, 2021. (Sue Surkes/Times of Israel)

Over the last 45 years, Solowey, who holds a doctorate in land reclamation and heads the institute’s Center for Sustainable Agriculture, has been testing plants, mainly trees, in an experimental orchard located just off the main road to Eilat at Kibbutz Ketura.

It’s a Sisyphean task. “There aren’t many fruits we can grow down here,” Solowey said. “I’ve tried around 500 from all over the world, of which maybe 10 show some promise. It’s either too dry or the water is too saline.”

Her latest major project is the creation of a shelter garden — a protected space in which some 70 species of threatened and endangered plants can mature before being introduced elsewhere as part of habitat rehabilitation. The garden will also serve as a preliminary test field for wild plants with the potential to be domesticated and later cultivated.

“We plant in mass [in the orchard]; in the shelter garden we only plant a few trees,” said Solowey.

Divided into eight sections, the shelter garden — located next to the experimental orchard — will showcase biblical plants, incense trees, global ethnobotany (native plants important to the culture and economy of particular peoples), endangered wadi (desert valley) plants, desert agroforestry, desert agriculture, a migrating bird habitat, and medicinal herbs. Many of the herbs are the subject of ongoing medicinal research and study that draws on the knowledge of local Bedouin.

She expects it to open to the public next year.

“Were hoping to do a lot of planting in the next month or so and are starting to make the paths and put down irrigation,” she said.

The project has already received the backing of the Israel Nature and Parks Authority — which Solowey hopes will lead to government funds.

Recently, Solowey was joined by Noach Marthinsen, 32, a desert agriculture researcher who hopes to continue the work started by Solowey and spends his days trying to learn as much as he can from a woman who is a walking encyclopedia and holds much of her accumulated knowledge in her head.

Marthinsen enthusiastically showed this reporter the mostly empty, beige area of sand out of which the new garden — funded by a former British council official, Robin Twite, in memory of his late wife, Sonia — will be carved. Among the plants already in the ground are a bodhi fig tree, a species under which Buddha is said to have achieved enlightenment, and a paloverde tree from the North American deserts.

Noach Marthinsen stands by a specimen of Balm of Gilead at Kibbutz Ketura in southern Israel, March 21, 2021. (Sue Surkes/Times of Israel)

“Not only will this be a reservoir for genetic material,” enthused Marthinsen, who has set up home at Kibbutz Ketura with his fiance and their dog. “It will be educational and awareness-raising and also a place for animal and bird life, with a wetland for birds.”

From ancient seeds sprout new fruit

Solowey, along with her partner in all things medicinal, Dr. Sarah Sallon, a pediatric gastroenterologist who directs the Louis L. Borick Natural Medicine Research Center at Hadassah Hospital in Jerusalem, is best known for having managed to germinate a 1,900-year-old date seed excavated at Masada, the fortress overlooking the Dead Sea — then the oldest seed ever brought to life.

While Solowey carries out everything that is directly plant-related, Sallon obtains the date palm seeds, organizes the genetic analyses and helps to get the scientific work published.

The Methuselah date palm in its own enclosure at Kibbutz Ketura in southern Israel, March 21, 2021. (Sue Surkes/Times of Israel)

That original sapling, named after the Bible’s longest-lived figure, Methuselah, now stands tall and proud near Solowey’s office. She describes it as “that big boy.” It is one of a long-extinct line of palms that were native to Israel but disappeared centuries ago.

The Medjool and Deglet Nour dates popular here today were brought to Israel from Iraq and Morocco by Jews in the early part of the last century. The only cultivated dates already present were limited plantations of Sayer dates planted by the Ottoman Turks.

When Methuselah turned out to be a male and thus not a source for fruits, Solowey went back to the germinating table, sowing 32 more ancient seeds of the same species as Methuselah, which yielded six saplings. These she named named Adam (after one of her six sons), Jonah, Uriel, Boaz, Judith, and Hannah.

Elaine Solowey (left) and Sarah Sallon enjoying the first Judean dates to be produced in several centuries, at Kibbutz Ketura in southern Israel, September 7, 2020. Hannah, the tree that produced the fruit, is in the background. (Marcus Schonholz)

Last year, pollen from Methuselah was used to fertilize Hannah’s flowers. That resulted in 111 dates.

“They’re the size of the Medjool, but they’re dry and have a lovely honey after-taste,” Solowey said, adding, “If they’d tasted terrible, I don’t know what I would have done.”

Pollen from the Methuselah date palm growing at Kibbutz Ketura in southern Israel, March 21, 2021. (Sue Surkes/Times of Israel)

This year, Hannah’s flowers have been dusted with pollen from Adam and Jonah as well as Methuselah. The dates — developing within the protective embrace of paper bags to keep the birds away — should be ready to eat in September.

Carbon dating has in fact revealed that the seed from which Hannah sprouted is 175 years older than the one that gave birth to Methuselah, meaning a new record. “We think [the seed] dates to between 30 and 65 [CE], and that her heritage is from a date brought back by the Jews who returned from the Babylonian Exile [in 539 BCE].

The other female plant, Judith, is still in Solowey’s greenhouse.

Striking it rich with oil

As head of the Center for Sustainable Agriculture, Solowey has focused on dryland agriculture, developing crops that can make the most of areas with limited water resources and earn farmers an income sustainably, despite fragile conditions in which minor changes to the climate can turn formerly arable land into deserts.

Drylands are found throughout the world and evidence suggests that they are expanding. Desertification is a major environmental issue that harms the land’s productivity and contributes to poverty.

It is this work that led her 29 years ago to become the first person to domesticate the argan tree, whose nuts produce an oil that is touted for its health benefits and is in high demand by the cosmetics industry worldwide. Argan trees require only a fraction of the water needed by date palms.

Solowey and her husband traveled to Morocco to receive their first batch of seeds from the late King Hassan himself.

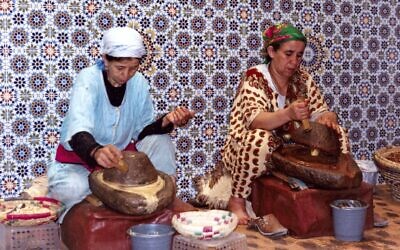

Moroccan women producing argan oil by traditional methods. (Chrumps , CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons)

In the Sous valley of southwestern Morocco, wild argan fruits are eaten by goats and then gathered from goat excrement after digestion. The nuts are pressed by hand to extract the oil.

Wild trees are genetically diverse and Solowey has been selecting the best specimens to produce a domesticated version which can be used for commercial argan oil production.

“We planted 1,000 wild trees, got 20 or so very good ones for this area, narrowed them down to seven or eight and we’re cloning them,” she explained, adding that samples have been passed onto the Hebrew University’s Faculty of Agriculture for further development. “I give [the plants] to everybody who asks,” Solowey said.

Argan fruits. (luisapuccini, iStock by Getty Images)

With pure argan oil in high demand, and mechanical processes replacing goat digestion, commercializing production is a potential cash cow, and Solowey’s son Nadav has set up an argan oil pressing facility within the kibbutz, which is now marketing several argan oil products.

The oil has been shown in studies to help cardiovascular health and boosters claim a laundry list of other health and beauty benefits.

“It’s good for the skin and the hair and if you eat it [in its roasted form] it lowers cholesterol,” Solowey said.

Marula fruit. (Ton Rulkens from Mozambique – Sclerocarya birrea – fruits Uploaded by JotaCartas, CC BY-SA 2.0, Wikimedia Commons)

Other species with promise include the so-called soap berry tree, whose oil has potential for use as a natural washing machine detergent, and marula, native to South Africa and Botswana, whose fruits are being used to produce oil and a liqueur. Azadirachta indica, a medicinal tree already known as a natural pesticide, is being cultivated to serve as a shade tree, while the salt tree and the palmate fig hold out the promise of sustainably growing edible fruit.

Solowey’s main interest is in trees, but she is eager to domesticate a variety of local, wild shrubs as well, among them the Judean wormwood, species of desert lavender and oregano, the desert stork’s bill, which produces edible tubers, the white bushy bean caper and the hairy thorn plum, the latter reduced in the wild to only a handful of plants.

Desert Stork’s bill — Erodium crassifolium. (Eitan Ferman, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons)

This year, she retired from teaching, meaning she’ll have more time to pursue these projects and possibly do some sightseeing as well. She dreams of traveling to Oman to see frankincense tree growing in the wild, and to Yemen’s scorched Socotra island, home to an abundance of plant species found nowhere else in the world.

“I’ve taught 50 semesters [at the Arava Institute], which is enough punishment,” she laughs. “Now, I’m an emeritus.”

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

May 12th, 2021

May 12th, 2021  FAKE NEWS for the Zionist agenda

FAKE NEWS for the Zionist agenda

Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: