Above Photo: From rimediacoop.org

Though she is not the tallest person in Providence, one local housing advocate casts a long shadow in her fight against gentrification. The following is a case study of that urban phenomenon that is intended to center her voice in the discourse and emphasize how important it is to provide such venues.

In a very broad sense, any sort of journalism that deals with gentrification as an urban phenomenon requires a significant understanding of the process’s political economy and how that informs an understanding of not just a financial dimension but also the geographic and political spheres. Putting it another way, a proper reporter on the issue of gentrification must account for the behavior of landed capital that finances the process, the space in which the process takes place, and the elected officials who pass laws and statutes that permit the process to move forward. Ergo reporting on gentrification in Providence requires a firm connection to both local populations impacted as well as the utility of public records that can illuminate the inner workings of the process and its sponsorship on the state and local level by public and private capital.

One textbook example of how not to report on gentrification is provided by a January 2015 story carried by Slate titled The Myth of Gentrification with the sub-headline “It’s extremely rare and not as bad for the poor as you think”. An April 2016 analysis by Project Censored says “Although gentrification receives frequent coverage in the corporate news media, such coverage often simplifies the stories of the working class people and families that are displaced, by simply reporting that they were unable to pay their mortgages or their rent. However, more in-depth reportage…shows that in many of these cases even people who hold multiple jobs with respectable incomes can barely afford a place to live once a community is overtaken by gentrification.”

In these contexts the case studied is the southwest corridor of Providence, neighborhoods known as South Side, West End, and Olneyville. For sake of brevity, these efforts will focus exclusively on a single plot of land now under development, 93 Cranston Street, which was formerly the location of the industrial Louttit Laundry. Cranston Street forks off of Westminster at an intersection with Winter and Fricker Streets, adjacent to the complex of high schools and administration buildings that make up a city block occupied by the Providence Public School district.

“The city was supposed to give us a site and they came up with was Louttit Laundry. And we saw the environmentals on that site and environmentals are where you look at what is in the ground. Does the ground have lead, anything that may be toxic, to people, causing people to be sick? So when we saw that, the environmentals, to that site, it was horrendous, I mean the real scary part is for a number of years that building was open and you could look in the windows and see where there had been kids in the building that were doing graffiti and that meant that those kids were exposed to the toxins that may have been floating throughout that building and whether or not these kids had actually gone into the basement of the building whereas there were these tanks of cleaning waste that was [sic] left in the basement.”

Click Player Below to Listen to Full Interview with Tigrai!

“So when I heard that, because it became a public notice that there was a group that was looking at that site to put a cooperative market there, I was interested in it because that site being designated as basically unfit for almost anything to be there. So I started looking into it and I started writing the city about the conditions, any construction that was going to happen on that site and how the people in Wiggins Village, the people in Garden Court, the Providence School Department, particularly the Tech school and Central High School, should have been notified that that site was going to be unburied and it had to be…remediated. Remediated means the ground has to be dug up, the dirt maybe removed, maybe filtered, any volatile chemicals or solid waste needs to be removed, and that process, neighboring people, they have to be notified, and the removal process has to be really protected until the covering, the work area, keeping the soil wet so that it doesn’t become air-bound, and that’s why I got involved in it because I’m very concerned about environmental issues in the city of Providence, particularly when it’s in a neighborhood with children. So I did go to a City meeting where I met some of the Urban Green people and the developer. In addition to a cooperative being there, a food cooperative, there’s going to be housing there…there’s going to be apartments. Not family apartments but probably individual apartments, maybe if a family had one child, that might be the limit, two might be the maximum. But pretty much…single adult apartments.”

AS: And certainly not subsidized or anything along those lines I would imagine.

AT: Right, not subsidized.

AS: So that is part and parcel of perhaps further gentrification in the neighborhood.

AT: Right.

In order to let both sides have equal time, I gave a phone call to Phillip Trevvett, who is on the board of Urban Greens. My questions specifically addressed the issue of gentrification and I will let the audio speak for itself.

Click the Player Below to Listen to the Interview!

Along with this interview, I also obtained from the Commerce Corporation meeting minutes and resolutions that provided a tax stabilization deal for the Cranston Street site. For ease of reading I have highlighted the major sections in the document dealing with the Cranston Street site.

East Providence-based Bourne Avenue Capital Partners, one of the financial backers of the project, is run by David and Ethan Sluter. And when architect Christine West of Kite Architects made a presentation for the West Broadway Neighborhood Association, well-known for its gentrification tendencies, their invitation text, according to the ProJo, said:

“In its heyday, the Louttit Laundry complex was an integral part of the neighborhood,” the association said in its invitation to neighbors. “Later, the historic building was abandoned for years, was a victim to fire, became a Brownfield site and was sadly demolished. Learn about plans to return vibrancy to this important neighborhood location!”

Gentrification is not a passive occurrence that happens because of the natural tides within the capitalist ocean. Instead it is an intentional act taken up by the upper classes in a given municipality to implement a definite and calculated program, breaking up historically progressive voting blocs within the urban landscape that have materialized and solidified from within working class population centers. These voting blocs pose a definite threat to the unhindered free flow of capital by favoring progressive tax codes, rent control, community land trusts, a robust social safety net, strong public education, and other elements of what would be a vibrant social democratic welfare state. Glen Ford of Black Agenda Report has previously written that “…Blacks most resemble the Scandinavian Social Democrats that Bernie Sanders sees as his model. The noted Black social demographer Michael Dawson’s studies have shown that the biggest bloc of Black voters are most like Swedish Social Democrats, and that a very large number of them are ‘more radical than that.’” One major failing of the discourse about gentrification is a tendency that leans towards paternalism and a charitable mentality for its victims while failing to mention that this is definitely a political program engaged in a type of suppression of progressives/radicals in a different form but similar fashion to the COINTELPRO policies of the last century. It is a systemic instance of class warfare that functions in a much more effective way than overt state suppression ever has.

As such, the reporter on the gentrification beat needs to begin by having a firm grasp of the political economy. This is gleaned from a thorough reading of both the article/primer Gentrification: What It Is, Why It Is, and What Can Be Done About It by Dr. Kate Shaw as well as the late Dr. Neil Smith’s book The New Urban Frontier: Gentrification and the Revanchist City.

Smith’s approach is impressive because he begins using the case study of the Lower East Side of New York in the 1980s before defining the phenomenon on the basis of two explanations, the micro/local neighborhood/rent gap theory and macro/global/uneven development theory. The first begins from an individualist perspective of consumer autonomy that Smith deconstructs as neoclassical economic notions from a historical materialist perspective.

According to these theories, suburbanization reflects the preference for space and the increased ability to pay for it due to the reduction of transportational and other constraints. Gentrification, then, is explained as the result of an alteration of preferences and/or a change in the constraints determining which preferences will or can be implemented. Thus in the media and the research literature alike, and especially in the US, where suburbanization bore such a heavy cultural symbolization, gentrification came to be viewed as a “back to the city movement.”… I present some empirical information from Society Hill in Philadelphia as a means of challenging the traditional consumer sovereignty assumptions expressed by the “back-to-the-city” nomenclature. The next section examines the importance of capital investment for the shaping and reshaping of the urban environment, and this is followed by an analysis of disinvestment—a vital but widely ignored determinant of urban change. Finally, I try to bring these themes together in the proposal of a “rent gap” hypothesis for the explanation of gentrification.

Rent gap is the difference between potential and actual ground rent capitalized under land use by the ownership. “Gentrification occurs when the gap is sufficiently wide that developers can purchase structures cheaply, can pay the builder’s costs and profit for rehabilitation, can pay interest on mortgage and construction loans, and can then sell the end product for a sale price that leaves a satisfactory return to the developer.”

Practical application in Providence is demonstrated with the case of the West End. “Gentrification in the southwest side actually started probably in the late ‘70s, particularly in the Elmwood neighborhood,” says Tigrai. “And those houses were really attractive because they were historic houses and they had a certain beauty and brought back the Victorian days for a lot of white homesteaders. The West End was predominantly in the ‘70s and ‘60s…working class low- and moderate-income Italian families. And as their income got better, they moved out and the people that lived on the side of the West End where Central High School is, that side all the way down to West River, that part was predominantly Black and those people moved more into the West End and West Broadway neighborhoods. In the ‘70s, there really wasn’t any Latinos to really talk about. That population was very small.”

“The Latinos really did not make a noticeable mark in the West End until probably the middle of the ’80s, 1985-88”, says Tigrai. “Those populations basically stabilized in terms of being residents in that neighborhood since I would say the 70s and the 80s and the 90s and 2000s until maybe 2008 or ’09. So essentially because Brown University, Rhode Island School of Design, those populations, which are predominantly white, those student populations were no longer able to have access to housing on the East Side. Those neighborhoods like Fox Point, Mt. Hope, the neighborhood around the hospital, Blackstone Boulevard, they started looking for other places to go and they started looking at the West End because that was the neighborhood most in transition, people moving out, houses being available at really affordable costs and they decided to settle in that neighborhood.”

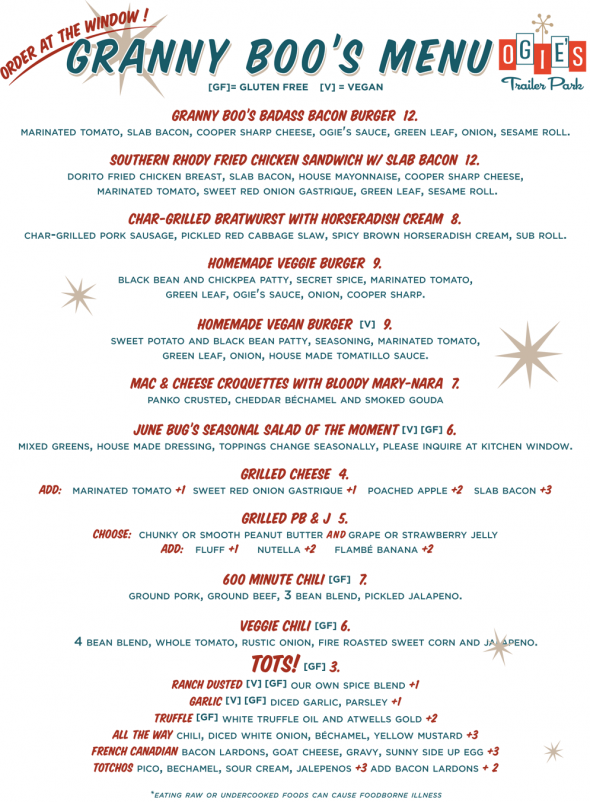

The most blatantly obvious sign of gentrification creeping into the West End neighborhood materializes in Ogie’s Trailer Park restaurant, located at 1155 Westminster Street. Here we have a trendy upscale hipster diner serving mid-level menu offerings that is intentionally styled as an enclave of low-income white working class people.

What is so galling about this establishment is that they literally built the place directly across the street from a low-income housing complex! Leaving aside the full frontal assault on aesthetic sanity which this garish crater in the landscape so obviously embodies, the notion of creating a restaurant whose decor theme spoofs and fetishizes rural poverty within less than 25 yards of those living in urban poverty would make the Marquis de Sade beg for moderation.

Smith continues his analysis:

[G]entrification represents a significant historical geographical reversal of assumed patterns of urban growth intimately connected to a wider frame of political-economic change. Gentrification occurs in cities in at least three continents, and is closely connected with what came in the 1980s to be seen as “globalization.” We need, then, to come at gentrification from the other side as well, from its position in the global economy. This is perhaps best achieved by trying to understand gentrification in terms of the “uneven development” of the global and national economies… [A] restructuring of urban space has been afoot since the 1970s, and while this restructuring certainly involves such “factors” as the baby boom, energy prices and the cost of new housing units, its roots and its momentum derive from a deeper and very specific set of processes that we can refer to as uneven development. At the urban scale, gentrification represents the leading edge of this process.

In a historical sense, the real estate industry effectively and efficiently abandoned development within the urban cores of cities worldwide after World War II as a substantial number of white working families, made economically mobile by the New Deal and wartime veteran welfare policies such as the GI Bill of Rights, moved into the suburbs. This strict segregation of lily white suburbs surrounding the urban cores, reinforced by redlining policies in the housing market and barring people of color from access to welfare state entitlements, led to a degeneration through intentional neglect that was described with terminology derived from healthcare, including phrases such as “decay”, “rot”, or “degeneration”. This description of geography effectively and successfully communicated not just and Other-ing of the buildings but entire populations living within them. This lexicon extends during the implementation of gentrification into verbiage that describes the urban landscape as a “frontier” and “wilderness” that these new residents must “civilize” and “tame”. In other words, it is the application of a settler-colonialist discourse to the urban centers that once were jumping-off points for such expeditions during the classical colonial period.

This is necessary so to facilitate and accommodate the movement of capital.

As Harvey (1978, 1982) has shown, there is a strong empirical tendency for capital to undergo periodic but relatively rapid and systematic shifts in the location and quantity of capital invested in the built environment. These geographical or locational switches are closely correlated with the timing of crises in the broader economy. Crises are not accidental interruptions in some general economic equilibrium, as neoclassical economic theory would suggest, but are integral instabilities punctuating an economic system based on profit, private property and the wage relation. The necessity to accumulate leads to a falling rate of profit, an overproduction of commodities, and thereby to crisis (Marx 1967 edn.: III,Ch. 13). Gentrification is intimately intertwined with these larger processes… The underdevelopment of the previously developed inner city, brought about by systematic disinvestment, provoked a rent gap which, in turn, laid the foundation for a locational switch by significant quantities of capital invested in the built environment. Gentrification in the residential sphere is therefore simultaneous with a sectoral switch in capital investments.

In local terms, the profession of public school teaching provides a very concrete explanation of how Providence has been treated in the past century. During the 1950s-1980s, Providence public school teachers would work in the city and then alienate themselves from their labor (namely their students and communities they worked in) by commuting back home to the suburbs of Cranston, Johnston, and Warwick (jestingly known as White-wick). These were the unionized middle class in the Keynesian epoch. As a brief aside, the challenge presented today to public school teachers, for them to become parts of their communities by moving into the neighborhoods where their schools are located, can very well contribute to gentrification in that community, posing a greater challenge to educators and their students. Teachers moving into these neighborhoods would bring with them a credit score, car, and household appliances that would promote despite intentions proactive “broken windows” policing in these neighborhoods unless special care was taken to prevent this.

By contrast, gentrification’s shock troops are non-union working professionals who embody a corporate-friendly multicultural identity politics. Dr. Adolph Reed has written that “[identity] politics is not an alternative to class politics; it is a class politics, the politics of the left-wing of neoliberalism. It is the expression and active agency of a political order and moral economy in which capitalist market forces are treated as unassailable nature. An integral element of that moral economy is displacement of the critique of the invidious outcomes produced by capitalist class power onto equally naturalized categories of ascriptive identity that sort us into groups supposedly defined by what we essentially are rather than what we do.” In this sense these shock troops, knowingly or not, have co-opted and utilized the grammar and vocabulary of then New Left/post-colonial liberation struggles to effectively delegitimize critiques of capitalism and its impacts upon targeted populations.

In Providence, private college students also play a major role in this and ironically are usually the most vociferous exponents of the anti-oppression discourse. In a general sense they are extremely well-versed in inter-sectional theory and its application. Yet simultaneously their attendance at colleges who are slowly starving the city to death owing to a lack of tax revenues derived from properties they own is one of the major engines of austerity in the city and only taxation of those properties would improve the situation, something Brown would never allow. Ergo there is fundamentally no positive role to be played by these students from these colleges regardless of how well they know the discourse and utilize it in their own interpersonal affairs.

Tigrai describes the behavior of this gentry as such. “My big concern is the removal of people of color, Blacks, Latinos, Asians, out of the West End because it’s putting those families in a housing crisis. And for young white people to be moving in the neighborhoods, talking about they want to live and experience the diversity, experience the cultures of people of color, it’s a pretense to steal the neighborhood. Generally that’s selling a bad bag of tricks.”

With an understanding of gentrification as a political movement in mind, one returns to a classic query that remains relevant, namely, what is to be done? David Harvey offers one answer:

We live, after all, in a world in which the rights of private property and the profit rate trump all other notions of rights. I here want to explore another type of human right, that of the right to the city. Has the astonishing pace and scale of urbanization over the last hundred years contributed to human well-being? The question of what kind of city we want cannot be divorced from that of what kind of social ties, relationship to nature, lifestyles, technologies and aesthetic values we desire. The right to the city is far more than the individual liberty to access urban resources: it is a right to change ourselves by changing the city. It is, moreover, a common rather than an individual right since this transformation inevitably depends upon the exercise of a collective power to reshape the processes of urbanization. The freedom to make and remake our cities and ourselves is, I want to argue, one of the most precious yet most neglected of our human rights.

From this springs a nationwide coalition movement that fights for the Right to the City.

In Providence, the Environmental Justice League and Direct Action for Rights and Equality are members of this coalition that are taking on these issues with vigor and can use support from the wider Rhode Island community. Harvey has written his own book on this topic titled Rebel Cities: From the Right to the City to the Urban Revolution. John Hope Settlement House, Tigrai’s institution, also remains a viable agency that is more than worthy of support and assistance as one of the oldest serving its target demographic in the state.

Source Article from https://popularresistance.org/housing-activist-asata-tigrai-on-gentrification-in-providence/

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

June 3rd, 2017

June 3rd, 2017  Awake Goy

Awake Goy

Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: