On the 19th anniversary of her father’s passing, Dr. Rabab Abdulhadi shares two sets of diary notes she wrote. The first was in 2003, a couple of weeks after her father passed on December 20, 2002, during the Aqsa Intifada. The second was on the 10th anniversary of his death, on December 20th, 2016. A version of these notes were published as “Resisting and Dying Under Occupation,” in If This be Madness: An Anthology to Honour the Life and Courage of Shamima Shaikh, edited by Vanessa de la Fuente and Na’eem Jeenah (2019). Dr. Abdulhadi is working on a manuscript on Palestinian experiences in growing up and resisting the occupation.

Lucky in Death? January 2003

Losing a loved one is heartbreaking. For me, losing my father has been particularly devastating not only because I loved him so much and I miss him terribly but also because a loss of life and personal tragedies under occupation and continuous curfew and siege are multiplied. My mother, siblings and I kept wondering whether he would have lived longer had he been residing in another place where access to medicine and specialized care was possible. But he refused to leave his land. He was born in Palestine and he wanted to die in Palestine. He was buried in Palestine!

Throughout his illness, we could not get an oncologist to see him. At the time, there were none in Nablus or the rest of the West Bank (had there been one, the problem of regular supervision and visits would have remained because of the siege). Last summer, I wrote about the impossibility of finding a head of lettuce in all of Nablus for two months. The medical situation is even worse. Blood is in short supply as a result of injuries. Doctors can only travel in ambulances under extreme and dangerous conditions and sometimes ambulances are not even allowed passage.

Ordinary things that cancer patients elsewhere might take for granted, such as spending a day walking or driving around to change their mood, were not available for my father. He spent the last months of his life cooped up in the house. When I was there in July and August, I would try every so often to ask him if he wanted to go for a ride and he would refuse saying that “if they stop us, you can walk, but ya habibti you know that I cannot. What would I do then?”

I would have very much liked to show him a good time, to cheer him up. I would have liked to accumulate more memories to remember him by but I was not allowed. It kills me that I could not do more short of getting him and my mother out of the country to join the other millions of Palestinian exiles. A number of friends asked me when I returned in August why I could not bring them to the US. Where would you begin to explain that they would have died even earlier were we to take them out of their home? So, my siblings and I accepted their decision and tried instead to visit them in Nablus as often as we could.

I wish that I had been able to spend more time with him or to say goodbye properly. I wish that the occupation had not scattered us all over this earth or made possible the simple act of saying a proper goodbye to a loved one on their deathbed. I had been planning to surprise my dad on his birthday, December 16th as I have done a few times in the past since I received my US residency and thus the freedom to travel across international borders. My inability to catch my scheduled flight, however, delayed my arrival in Nablus a day too late. By the time I arrived, my father was already admitted to the Intensive Care Unit. Instead of going to my parents’ house to take a shower and change after an 11-hour flight, I had to go directly to the hospital. It was not a choice. I could not risk the real possibility of being held up for hours or worse yet, turned back by any of the multiple checkpoints the Israeli military had set up throughout Nablus. I stayed at the hospital with my mother for the last three days and three nights until he passed away nineteen years ago today. I’d like to think that he heard me when I talked to him. I want to believe that he tried to tell me that he heard me by pressing my hand and lifting his eyes. Once in a while, a tear would drop from his eye. I would never know if it was a reaction to what I said or his own physical state. The sympathetic doctors did not know either but they would not deny the former, probably because they thought that it didn’t make a difference to their patient’s state but it did matter a great deal to me.

My sister, Reem, was not so fortunate. She could not make it to see our father or to be with the rest of us even for the funeral and the 3za (mourning). The last time they saw each other was at the airport in London in July. She was hoping to receive her British citizenship and go home but as a Palestinian, she had chosen the wrong time to apply. We called her that morning and told her that he was not doing too well. Would she like to say a few words? We placed the cell phone next to his ear. She said farewell to her father across phone lines and continents. As sad as this sounds, I thought that Reem was still “luckier” than our sister-in-law, Lana, who was unable to say goodbye to her mother who was shot and killed by Israeli soldiers in Nablus in October 2002, while Lana was in Amman.

Imagine feeling lucky in death? But this is life in Palestine today. To be able to have a funeral is considered a fortunate development. To be able to bury our father in dignity is fortunate. Not to have a strictly enforced curfew that day is fortunate. In the midst of my sorrow, people who came to pay their respects at the 3za tried to relieve my pain. My late aunt Hoda (RIP) shared a story of a man who died two months earlier during one of the strictest curfew days in Nablus. For three days, his body remained at home in full view of his wife and his three little kids. As in the case of my father, no ambulances were allowed to drive around making it impossible for them to pick up the body. On the third day, as they watched their father’s body decompose before their very eyes, the children began to literally “go crazy.” Their mother was eventually forced to pick up the body of their father/her husband and throw it out of the window to the street. Imagine the nightmares that she and the kids would continue to have for the rest of their lives? Knowing of other people’s tragedies puts things in perspective. It never takes away the pain or lessens it one bit nor does it erase the effects of curfew and siege.

It was literally impossible to go in and out of Nablus on the regular roads—which were completely destroyed. The eastern part was now isolated from the western part by want Nabulsis called “Tora Bora”, a mound of dirt and asphalt erected by the Israeli military right outside the Nablus prison to cut off the eastern part. Our relatives and friends could not come from outside of Nablus to be with us and offer their condolences. Two of my brothers tried to go to Amman to stand in with my uncle in Amman to accept condolences on behalf of all of us. This story, too, did not end there. Samir, who is a disabled Palestinian with an Israeli issued ID, was turned back after being stuck for 12 hours while trying to get to the Israeli side of the bridge to cross to Jordan. Even after waiting 12 hours, Samir was refused exit and turned back to Nablus. Another simple act of honoring one’s parents was denied. The constant curfews, we could not get to the cemetery to visit our father’s grave; people could not get to my parents’ house to offer condolences.

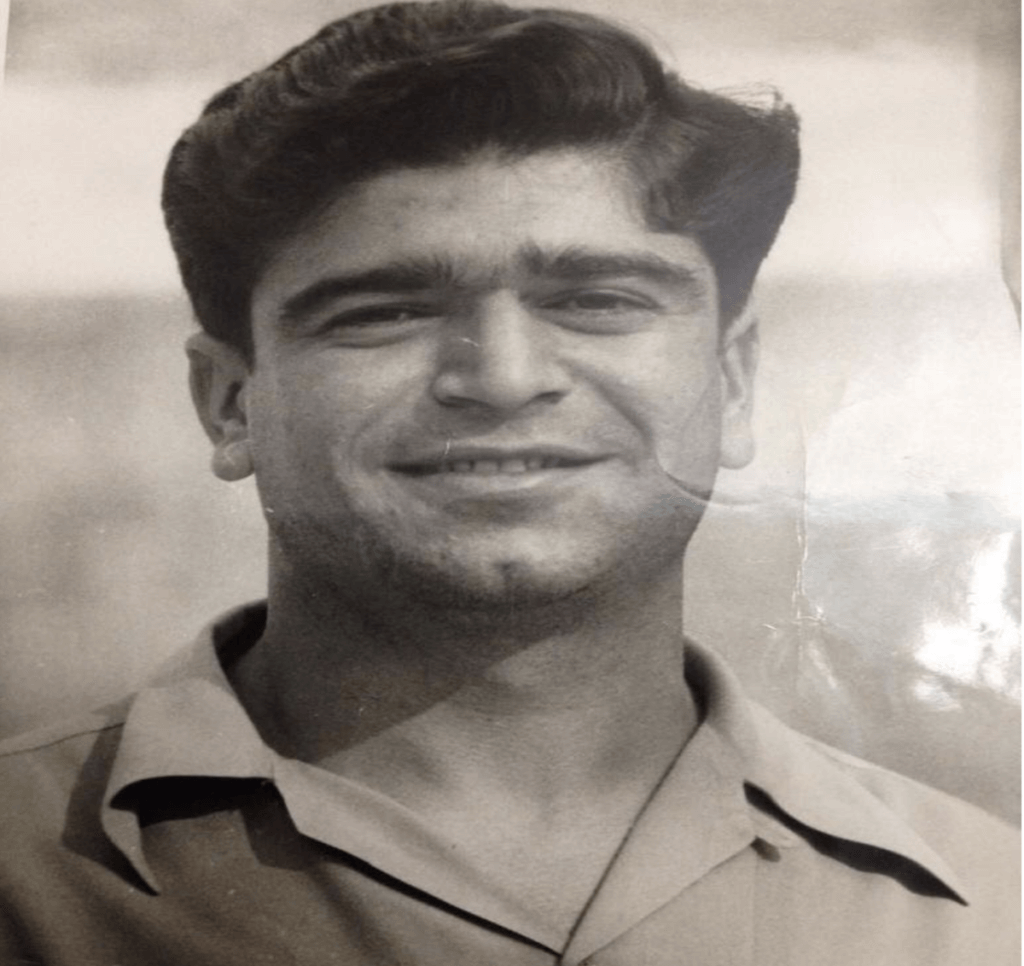

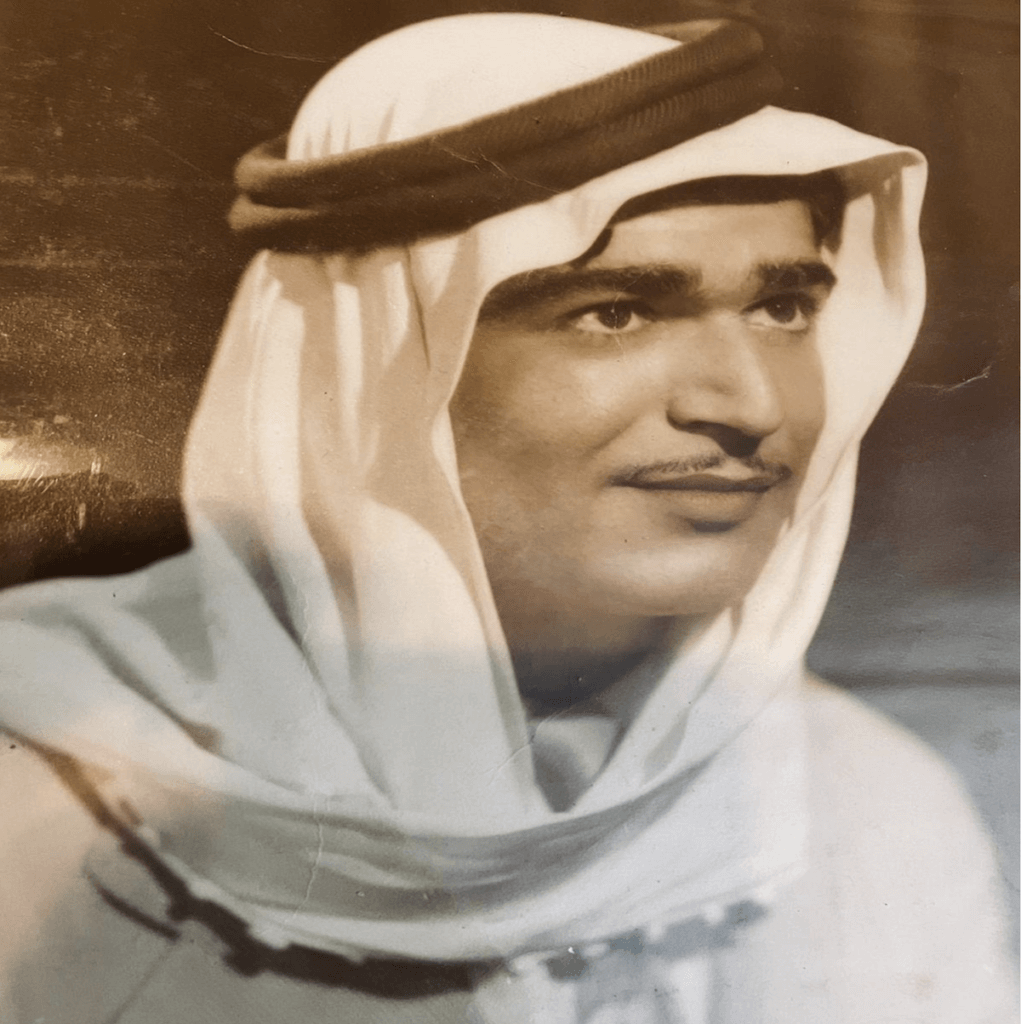

My father was a great man: warm, loving, modest, generous, friendly and with great social and political commitments. He and my mother insisted that my sister and I receive higher education to ensure our independence of the family and the men in our lives. He was a founding member of the Arab National Movement. He served on the board of trustees of Birzeit University and was an active supporter of the Women’s Studies Center. And he insisted on staying put in Palestine and refused to immigrate even as the economy got worse and worse.

On the 14th Anniversary of my father’s passing December 16, 2016

Today would have been my father’s 89th birthday if he had survived illness compounded by Israel’s brutal curfews in 2002 to the extent that neither the doctor nor the ambulance could get to him as his blood sugar dropped uncontrollably. Such is life for Palestinians under Israel’s colonial rule.

My dad studied at the University of Tennessee at Knoxville. He came to the US to study agronomy, having convinced his father (my grandmother had passed by then) to let him go far away to pursue his education. He wanted to return to Palestine to work the land of his family. He boarded a ship in the port of Haifa, Palestine, in 1947, and arrived in the US after one month. After the fall of Palestine in 1948, my father became stateless. The US government offered him a green card, which he accepted because he had no other choice. However, soon after he was drafted to serve in the US military to fight in the US war against Korea. He told me that this was not his war, that “the Koreans did not attack us. I had no business fighting them.” So he refused to join the US army. As a result, he was stripped of his green card. He was officially informed that he was excluded from visiting the US except for health or education purposes. He was also banned from applying for US citizenship. This earned him a place among the list of excluded persons. I had never thought about it until now, but my dad was a victim of McCarthyism.

The good people from the Harb family from Ramallah who had immigrated to and lived in Tennessee (and who had become a family for Palestinian students whose own families were back in Palestine) lent my dad money to pay for his tuition so he could complete his studies. He did and in 1952 he returned with his degree but the land to which he belonged was gone. Soon thereafter, he settled his debt to the Harb family, who were no longer just another Palestinian family in the US diaspora but were now Auntie Badia and Brother George. He joined the Arab National Movement of George Habash and Wadie Haddad that had just emerged to fight Zionism and colonialism and liberate Palestine.

In an interview that he agreed to give me after much resistance, he discussed not only his experience with McCarthyism (he did not name it as such but he was categorically clear that this was a US policy of penalizing those who disagreed with its colonialism and wars); he also described the horrible conditions of segregation in the US South and how he and other dark-skinned Palestinian students would be directed to “colored only” bathrooms and counters. He always felt a sense of solidarity with all those who fought for their freedom and saw the injustice in their cause.

Like other immigrant students, he worked his way through school to pay for his education. Every summer, he and other Palestinian students would drive north to Detroit to work in the auto factories, buy new cars to replace the old ones they had, and drive back to Knoxville.

On this day I miss you my dear baba and honor you and your legacy – a disposed Palestinian, a factory worker, an undocumented student, a victim of racism and McCarthyism, a fighter for Palestinian and Arab liberation, a haunting reminder of the brutality of Israeli colonialism and a loving and wise father.

BEFORE YOU GO – Stories like the one you just read are the result of years of efforts by campaigners and media like us who support them by getting the word out, slowly but doggedly.

That’s no accident. Our work has helped create breakthroughs in how the general public understands the Palestinian freedom struggle.

Mondoweiss plays a key role in helping to shift the narrative around Palestine. Will you give so we can keep telling the stories in 2022 that will be changing the world in 2023, 2025 and 2030?

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

December 21st, 2021

December 21st, 2021  Awake Goy

Awake Goy  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: