Above Photo: From Tens of thousands of cyclists turn out for the weekly Sunday ride along Paseo de la Reforma

For one morning every week, people on bikes and on foot rule 35 miles of central city streets, but it is not just about car-free Sundays – the world’s fourth biggest city is also building a network of protected bike lanes

Stand on Mexico City’s grand Paseo de la Reforma boulevard on a Sunday morning and you’ll hear gears whirring, bells ringing and the chatter of voices as 50,000 people cycle, scoot and skate along 35 miles of closed roads. Stop and listen on any other day of the week and all you’ll hear is the roar of 10 lanes of traffic.

This sprawling megacity of 21 million is home to 5.5m cars, and that number is growing despite some of the worst traffic jams in the world. Residents spend an average of three hours a day commuting, and car speeds during rush hour have fallen to around 7.5mph (12km/h). Although air quality has improved markedly since the city was named the most polluted in the world in the 1980s, walking or cycling along one of its many multi-lane highways sometimes feels as if you are sucking directly on a car exhaust.

For one day every week, though, people on bikes and on foot rule a decent stretch of road, for a few hours at least. The official Muévete en Bici (Move by Bike) event has been going since 2008 but was recently expanded to cover 35 miles (55km) of city streets. It’s not just for cyclists: many others jog with baby strollers, or enjoy free zumba classes, martial arts or Mexican wrestling displays.

Some might dismiss the weekly car-free morning as a gimmick, but Reforma is also home to wide, protected cycle lanes along both sides, from the historic centre to the green oasis of Chapultepec park in the west. During rush hour these lanes see a constant stream of cyclists in work clothes, many of them using the Ecobici bike hire system – the fourth largest in the world after Huangzhou, Paris and London. It is used mainly by residents getting around the city, rather than by sightseeing tourists, and 37% of users are women.

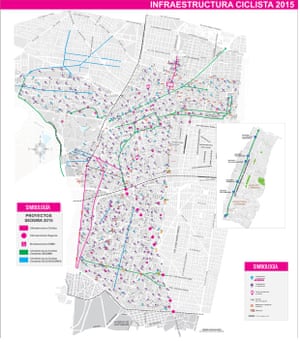

The city now has around 90 miles (150km) of dedicated bike lanes, and environment minister Tanya Müller last week announced two new protected cycle paths will be built along Revolución and Patriotismo avenues by February. A survey showed 4,000 cyclists a day already brave these high-speed, five-lane highways.

Sitting in her modern office overlooking the Zócalo – the historic main square, ringed by a six-lane road – Müller says cycling plays a crucial role in her attempts to make the city more sustainable and helps to fight pollution, congestion and obesity.

She has expanded the Ecobici network to more than 6,000 bikes at 444 stations, and users can now access the service using an integrated card that also covers the metro, bus rapid transport (BRT) and trolleybuses. In an effort to include the majority of residents who live on the outskirts of the city, the environment ministry has opened a 24-hour 400-space secure cycle parking facility at Pantitlán near the airport in the east, and another is being built in La Raza in the north. The idea is that people can cycle from home to the hub, take public transport into the centre and then use an Ecobici for the “last mile” to work.

Another proposed cycle lane along División del Norte has been stalled for years after protests from the plumbing and building suppliers whose shops line the route who are worried it will damage trade. “The scheme is on hold but it will happen,” promises Müller.

Trendy cycling cafes and shops are springing up in cooler parts of town like Condesa and Roma, where the pace of the city is slower and drivers are more used to seeing people on bikes, tending to give them more space. The last time an official survey into cycling was completed eight years ago it showed 1% of journeys across the metropolitan area were made by bike. Unofficial estimates now put that at around 2%.

Bernardo Baranda of the ITDP, which works to help developing countries improve their transport systems, was one of a group of cyclists who helped start the grassroots Bicitekas organisation in the late 1990s after he returned from a period studying and working in the Netherlands.

Inspired by the efforts of Bogotá mayor Enrique Peñalosa, in 1998 the collective started a weekly Paseo Nocturno, a Critical Mass-style ride where a group of cyclists meet up on a weeknight and take a four-hour trip around some of Mexico City’s busiest roads, staying safe through sheer force of numbers. It was revolutionary at the time but now the city hosts an official Paseo every Sunday and a government-organised night ride once a month on closed roads; last month’s for Day of the Dead attracted a record 95,000 cyclists. There are plenty of unofficial night rides, too, run by groups such as Mujeres en Bici and Paseo de Todos, as well as the original Bicitekas ride.

Cycling activists galvanised around protests against the Segundo Piso in 2003 – a second tier to the city’s car-choked multi-lane Periférico ringroad – but it wasn’t until the arrival of Marcelo Ebrard as mayor that things began to change. Hisoriginal 2007 target of 186 miles of cycle paths has still not been achieved, but he and environment minister Martha Delgado started the official Sunday rides, built the bike lane along Reforma and launched Ecobici. There is a feeling among activists that, while Müller and current mayor Miguel Ángel Mancera are working in the right direction, they are nowhere near as radical.

Cycling with Baranda on some of the city’s protected cycle lanes it is soon clear that a bike is a quicker way to get around than a car, especially on journeys under three miles (5km). For the most part, concrete and heavy-duty plastic dividers keep the traffic at bay, although when they are replaced by reflectors in the road in the run-up to a junction some drivers simply swing into the bike lane. I soon learn to be incredibly cautious every time the bike lane passes a side road, as cars from behind will happily pull alongside and try to turn right across your path. Venture away from the cycle lanes and it quickly feels more aggressive.

Baranda would like to say cycling here is safe, but last year suffered his first serious accident in two decades when he was overtaken by a truck and a ladder poking out of the side caught him on the back of the head. The driver didn’t stop and Baranda spent a month in a neck brace. He’s now back out on his bike.

Around 1,200 people are killed on Mexico City’s roads every year. Of these 60% are pedestrians, but it is not clear how many are cyclists. A third of accidents involve speeding cars.

Baranda would like to see more protected bike lanes but is hopeful a new traffic law, about to come into force, will make cycling safer. Speed limits are being cut to 30mph (50km/h) on main roads and 20mph (30km/h) on side streets, cyclists will be allowed to proceed through red lights if the way is clear, and the city government will put the needs of pedestrians first, followed by cyclists, then public transport, cargo and finally private cars and motorbikes.

But the tougher traffic laws will only work if the police make them work. “You need consequences for bad driving,” says Baranda. “The police need to enforce the law.”

That point is echoed by Agustín Martinez, the president of the Bicitekas collective. “Not everyone is studying traffic law like we are – drivers need to be educated and we need enforcement. A car can jump a red light right in front of a traffic police officer and he won’t do anything – the law is very flexible in Mexico City.”

I ask about a white ghost bike I spotted on the way to theBicitekas HQ. One of the group explains how a young female cyclist was hit by a car and knocked unconscious. When she got up and her boyfriend started remonstrating with the driver, he drove off with the woman clinging to the bonnet, accelerating and swerving until she fell off. She died of her injuries in hospital. The driver was tracked down by police but, says the activist, was freed after a few well-placed bribes: “When he was caught he said, ‘I have money, I have power, nothing will happen’ – he was right.”

Martinez is pleased with the new traffic law but disappointed with what he sees as the lack of recent progress. “We have a lot of friends in the city government now and we thought everything would change,” he says. “But it’s hard, their hands are tied. [The city government] is scared of the car lobby, they defend old ideas like cheap gasoline, they are scared of business and they don’t think about the people that live here. It’s all about money.”

There’s no doubt that Mexico City is for the most part still a car-orientated city but it is also clear that cycling is in the ascendancy. “It used to be that people saw cycling here as something eccentric or crazy,” says Baranda. “People thought that if you cycled you must be a tree-hugger or not have enough money to get a car, but that’s changed now – now it’s trendy.”

Source Article from https://www.popularresistance.org/viva-la-revolucion-mexico-city-cyclists-fight-for-right-to-ride-in-safety/

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

November 11th, 2015

November 11th, 2015  Awake Goy

Awake Goy  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: