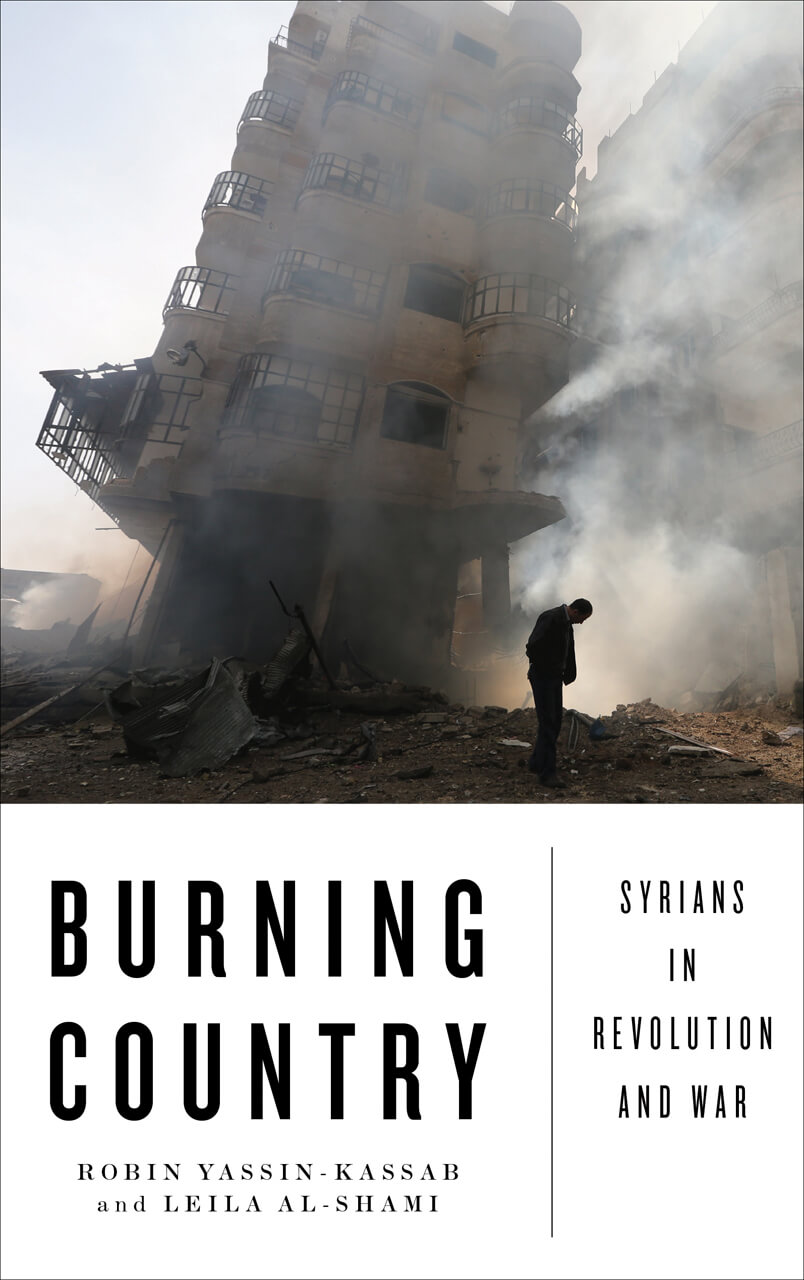

Residents queue up to receive humanitarian aid at the Palestinian refugee camp of Yarmouk, in Damascus, Syria, March 11, 2015.

The following is an excerpt from Burning Country: Syrians in Revolution and War (Pluto Press) by Robin Yassin-Kassab and Leila Al-Shami. You can buy the book here.

According to defected diplomat Bassam Barabandi, “Assad learned from the Libyan case that a hasty resort to large massacres, or the threat thereof, could draw intervention from NATO forces. A slower increase in violence against opponents, however, would likely go unchecked.” [1]

The military escalation was slow but certain. From February 2012, heavy artillery regularly beat down on Homs, very often on civilian neighbourhoods containing no military targets. By June 2012, helicopters routinely fired missiles and machine gun rounds on rebel- controlled quarters. The jet bombing of Aleppo was underway by August. Later in 2012 came the cluster bombs and ballistic missiles. In December the first scud missiles were fired at the Shaikh Suleiman base in Aleppo. A month later they were being directed at densely packed civilian zones in Aleppo and Damascus. And the worst escalations would soon starve the capital’s suburbs.

In July 2012, as the Tawheed Brigade prepared for the push into Aleppo, the FSA advanced into inner Damascus for the first time.

Gun battles raged in the city centre. In response, regime tanks and helicopter gunships struck the neighbourhoods of Meydan, Tadamon, Hajr al-Aswad, Kafr Souseh and Barzeh. The heavy artillery dug into the mountain above the city rained fury on the suburbs below. For Abdul Rahman Jalloud – on the run in the Damascus suburbs – it was a turning point:

I used to say, if 100,000 die every day, we still shouldn’t militarise. I changed my mind during the first battle of Damascus, July 2012. The first shelling in the capital was on Tadamon, on the 19th. It was a shock. It outraged everybody. Even some regime supporters were protesting. We burned fires in every street in Damascus, and for a while the regime was frightened enough to stop the shelling. The police hid in their stations and the security in their branches. They took down some checkpoints so it became easy to move around, even during the battle. [2]

In part, the regime was responding to the 18 July bombing of the military crisis unit in Damascus, the single most grievous blow directed at its heart. Three key officials were killed: Defense Minister Daoud Rajha, Presidential Security Adviser Hassan Turkmani, and Deputy Defense Minister (and Assad’s brother-in-law) Assef Shawkat. Intelligence Chief Hisham Bekhtiyar was seriously wounded, and there were unconfirmed reports that the president’s brother Maher lost a leg. [3]

The FSA’s Damascus offensive was beaten back, and through the latter half of 2012 regime forces were increasingly reinforced by Hizbullah and Iraqi Shia militias such as Asa’ib Ahl al-Haqq and the Abu Fadl al-Abbas Brigade. By the spring of 2013, all the revolutionary suburbs of the western and eastern Ghouta were under siege.

The Palestinian-Syrian citizen journalist Qusai Zakarya experienced the impact in Moadamiya, in the western Ghouta:

I saw the full impact of Assad’s ‘starve or surrender’ weapon myself. In October 2012, Assad’s forces commenced a total siege on Moadamiya, blocking all food, medicine, and humanitarian supplies from entering the town. While we initially found sustenance from a bumper crop of olives, food began to run out as winter set in, and residents were reduced to eating weeds and stray animals … I consoled parents on the deaths of their young children – such as my friend Abu Bilal, who was a grocer before the siege but could not even save his own daughter during it. Another friend of mine was desperate to get medicine for his dying daughter, but was caught by regime intelligence. We found him with his throat slashed and the skin peeled off his entire body. [4]

Lubna al-Kanawati was based in Harasta, in the eastern Ghouta, where the blockade was equally tight:

In June 2013, on the first day of Eid, the regime imposed a total siege on the eastern Ghouta. Snipers were essential to this – now it became impossible to smuggle food in through the back routes. Every day the Ghouta suffered mortars like rain. MiGs were in the sky from dawn to dusk. They used everything against us – elephant missiles, scuds, barrel bombs. It got worse and worse until the winter, which was terrible. People were eating leaves and animal fodder. The water supply didn’t work because the electricity needed to pump it was switched off, so people were digging wells in the streets. There was no medicine whatsoever, no sanitary towels, no Internet or mobile or landline. At one point the regime and the FSA made a deal and food came in, but at incredible prices. Eighty dollars for a kilo of tea, for example.

Speaking in southern Turkey in December 2014, Lubna complained she was still unable to control her eating, that she never felt full: “Hunger is the most effective weapon of all. A hungry person is an angry person who inevitably acts impetuously. Hungry people are incapable of helping each other. If you can’t help yourself, you can’t think of others. In the end people fought in the streets over food.” [5]

***

Another area where people starved to death was south Damascus’s Yarmouk camp, housing the largest Palestinian population in Syria, though Syrians live there too. In the late 1940s and early 1950s, the camp looked similar to those housing Syrian refugees today. People driven from northern Palestine, particularly the Safad area, lived in tents separated by muddy paths. Then shacks were built, which grew in the next decades into densely packed residential blocks.

Protests broke out in Palestinian camps in Lattakia and Deraa in 2011, and in Yarmouk too, though on a smaller scale than in neighbouring areas. Yarmouk’s restraint resulted from two factors: the prominence in the camp of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine-General Command (PFLP-GC), which acted as Assad’s shabeeha, and a genuine desire for neutrality in the struggle for Syria’s destiny. [6] This stance allowed the camp to offer refuge to Syrians displaced by repression elsewhere. During 2011, Yarmouk’s population exploded from around 200,000 to around 900,000. Throughout 2012 the neighbouring suburbs Hajr al-Aswad and Tadamon were subjected to repeated assault, as witnessed by Salim Salamah, who works with the Palestinian League for Human Rights – Syria: “I used to sit on my terrace in Yarmouk and watch Tadamon being brutally bombed, rockets passing over my head, and I could smell the burning meat.” [7] Activists and protestors from the camp were detained, often tortured to death, and shells and sniper fire rattled its perimeters, but still its neutrality was preserved – until 16 December 2012, when regime jets targeted a mosque, a school and a hospital, killing at least 40 people. The camp responded with furious protest; resistance fighters arrived from neighbouring areas the following day. From then on the camp was rebel territory; as such, it qualified for the full force of Assad’s collective punishment. [8]

Immediately a partial siege was imposed, with the PFLP-GC blocking the camp’s entrances and prohibiting the passage of goods. Hundreds of thousands of civilians were able to leave to become refugees once more, though the young men passing the checkpoints risked detention and murder. But tens of thousands remained, immobilised by illness or age, or wishing to stay with their property, or having nowhere at all to go.

On 8 July 2013 the siege became total. The Palestinian League for Human Rights reports on the results:

Some of the opposition armed factions began to steal from and seize warehouses containing relief supplies, failing to help the inhabitants endure the siege. The regime forbade the entrance of food and medical supplies, except occasionally a very small quantity of baby milk and one single delivery of polio vaccines … More than 170 died of various siege-related causes including starvation to the end of February 2014. After this especially harsh period, international humanitarian organizations and UNRWA [United Nations Relief and Works Agency] began to distribute aid supplies to the camp’s besieged residents, in the form of deliveries of parcels containing some foodstuffs. Despite the regime agreement and promises that civilians would be unmolested during food deliveries, dozens were arrested by regime forces present in the delivery area at the camp’s entrance, and dozens more were killed during delivery operations, either by snipers or in clashes between regime and opposition forces, both indifferent to the presence of civilians. [9]

The siege was reinforced shortly afterwards. By now Yarmouk’s emaciated residents were chewing boot leather and leaves; a cleric even issued an edict permitting the camp’s Muslims to eat stray cats and dogs. In June 2014 the water supply was cut off too.

***

By the summer of 2013, better-armed and organised opposition offensives had brought the Damascus front line to the edge of the city centre and only five miles from the presidential palace. For the regime this represented a greater challenge than the brief offensive of the previous summer; besieged in the Ghouta suburbs, rebels had nevertheless established and kept a bridgehead as far as Jobar and Abbassiyeen Square from which they might launch future strikes on the capital’s key installations. Repeated regime offensives had failed to dislodge them. Did this cause desperation in Assad’s inner circle? It certainly resulted in the most dramatic escalation yet.

At 4.45 in the morning of 21 August, Qusai Zakarya was preparing for bed after a sleepless night in the besieged western suburb of Moadamiya. Suddenly he felt ‘a knife made of fire’ tearing his chest.

Recognising a gas attack, Qusai called for the men nearby to get into the open air. Outside in the dark street his neighbour screamed that her three children were unconscious. Qusai helped to heave them into a pick-up before he lost consciousness himself. He was given up for dead when his heart stopped, but came round half an hour later vomiting white foam. [10]

Between 2.00 and 5.00 am similar scenes unfolded across the city to the east, in the rebel-held and fiercely revolutionary suburbs of Ain Tarma, Zamalka, Irbin, Saqba, Kafr Batna – distraught, panicked civilians screaming for their loved ones; men and women foaming at the mouth and nose; children convulsing; then rows and rows of white-shrouded bodies lined on pavements, hospital hallways, in mass graves.

Razan Zaitouneh witnessed it:

At the beginning, we thought that it’s like the previous times, that there will be only dozens of injured cases and number of murders, but we were surprised by the great numbers which the medical points received during only the first half of hour following the shelling. Things started to become clearer after that. Hours later, we started to visit the medical points in Ghouta to where injured were removed, and we couldn’t believe our eyes. I haven’t seen such death in my whole life. People were lying on the ground in hallways, on roadsides, in hundreds.

There haven’t been enough medical staff to treat them. There is not enough medications for more serious cases. They were just to choose to whom they will give the medication, because there is no medication for everybody. Even doctors were crying because they couldn’t help the injured people, because the lack of the medication and oxygen. The paramedics were telling us how they were breaking in doors and houses in Zamalka and Ain Tarma, where the shelling took place, and get inside and find whole families dead in their beds. Most of the children didn’t make it.

In cemeteries which we visited, victims were buried in mass graves, 15 or 20 dead bodies in every grave because the large number of injured people. People were – also there was hysterical between the people. Families are searching for their children. People were searching for their children in every town in Ghouta. Children in the medical points were crying and asking for their parents. It wasn’t believable. [11]

It was the deadliest use of chemical weapons since the Iran–Iraq war, the greatest single poisoning of civilians since Saddam Hussain’s slaughter of the Kurds at Halabja. Estimates of the dead reach 1,729 – so many because people were sheltering from the artillery barrage in their basements, the worst place to be, where the gas sank and thickened.

Even as spokesmen made official denials to the foreign audience, regime-associated webpages were celebrating the attack. [12] According to a defected general, “It happened for internal reasons. For weeks, the rebels have threatened Assad’s home province of Lattakia, where they have captured several villages … But many of the irregular fighters, which the government has used instead of the army, are Alawites from the region. Now they’re going back to protect their villages.” So the attack fulfilled the twin aims of “holding the thinned out front around Damascus and strengthening the morale of the fanatics in their ranks.” [13]

There may be truth to this version, but the attacks served a still greater function. The regime clearly believed – perhaps had been advised by Russia’s Vladimir Putin – that Obama’s threat to intervene if the chemical weapons ‘red line’ was crossed was empty. In this, as events soon showed, the regime was absolutely correct. Not only was no punitive action taken against it, the very possibility of action was removed from the table; implicitly, the chemical decommission- ing deal that arose in the aftermath handed the Syria file to Assad’s Russian sponsor. So the message of the sarin heard by resistant Syrians was this: no one’s coming to save you, not in any circumstances.

Lubna al-Kanawati, who’d been injured by mustard gas a week before the sarin strikes, observed the mood: “After Obama’s failure to act over sarin, a profound sense of depression and isolation afflicted the people. They knew they’d die hungry and in silence, ignored by the world.” [14]

***

The safest place to live is near the front line. In the civilian areas away from the battle – this is where the barrel bombs drop, where the artillery strikes. For the regime, the battle against the civil and political alternative is more important than the military battle.

Ziad Hamoud [15]

The regime pursued a scorched earth strategy. It was all very deliberate and self-declared. The shabeeha scrawled it on the walls: ‘Either Assad or We’ll Burn the Country’. In the countryside they killed livestock and burned crops. In the towns the army shelled bakeries, schools, hospitals and market places. Hundreds of barrel bombs dismantled Aleppo – more bombed than any city since World War II – and Deir al-Zor, Homs, Deraa and suburban Damascus. [16] Women feared the roads lest they were raped by shabeeha at checkpoints; men feared detention or forced conscription. The most obvious consequence of this terror was the mass expulsion of the population from the liberated areas, creating another World War II comparison – the greatest refugee crisis in seven decades.

Even as it destroys the old system, a successful revolutionary movement must create alternatives. When Syria (necessarily) became a battlefield, the voices of the civil organisers who’d made the revolution were increasingly drowned out by the thunder of bombs; and power – which in 2011 had been brought to community level – was increasingly claimed by authoritarian militia leaders competing for funds and local dominance. Syrian elites, such as the Coalition, were unable to establish a presence on the burning ground. If the FSA had been seriously supported from outside, if Assad had not been so generously armed and funded by Russia and Iran (these international factors are examined in Chapter 9), then the armed struggle might have lasted months rather than years, and civil activism might have quickly regained its role. But the war stretched on, and the liberated areas became death zones. This was the vacuum in which jihadism would thrive.

In June 2013, Ra’ed Fares, director of the media centre at Kafranbel and one of the symbols of the revolutionary movement, was asked if he’d have joined the protest movement in 2011 had he known what would happen next. He answered matter-of-factly:

“No. The price was too high. Just in Kafranbel we’ve had 150 martyrs. As many as that are missing; they’re probably dead too. As for me, I can’t cry anymore. I don’t feel properly. I’ve taken pictures of too many battles. I’ve photographed the martyrs.”

Hands on the wheel of his battered car, he shrugged his shoulders.

“But it’s too late now. There’s no going back. We have to finish what we started.” [17]

Notes

1. Bassam Barabandi and Tyler Jess Thompson, ‘Inside Assad’s Playbook: Time and Terror’, Atlantic Council, 23 July 2014.

2. Interview with authors, December 2014.

3. The bombing was apparently carried out by one of the inner circle’s body guards. Some reports describe it as a suicide attack, though when the FSA claimed responsibility for the operation it claimed the device had been remotely controlled.

4. Qusai Zakaraya,‘I Was Gassed by Bashar al-Assad’, stop the siege, 22 August 2014.

5. Interview with authors, December 2014.

6. The PFLP-GC, led by Ahmed Jibril, is a Syrian regime-backed splinter group from the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP). The mainstream PFLP denounced the PFLP-GC’s role in Yarmouk. See: www.al-monitor.com/ pulse/originals/2012/al-monitor/pflp-on-defense-in-gaza.html# (accessed September 2015).

7. Correspondence with authors, January 2015.

8. For an example of the political murders of men from Yarmouk, see the case of Khaled Bakrawi – in Palestinian blogger Budour Hassan’s words, ‘a 27-year-old Palestinian-Syrian community organiser and founding member of the Jafra Foundation for Relief and Youth Development. Khaled was arrested by regime security forces in January 2013 for his leading role in organising and carrying out humanitarian and aid work in Yarmouk Refugee Camp. On 11 September, the Yarmouk coordination committee and Jafra Foundation reported that Khaled was killed under torture in one of the several infamous intelligence branches in Damascus.’ in ‘Death under Torture in Syria: The Horrors Ignored by Pacifists’, Random Shelling, 15 September 2013.

9. Palestinian League for Human Rights-Syria, ‘Camps Without Water: Legal Report on the Cutting of Water to Yarmouk and Deraa Palestinian Refugee Camps in Syria’, see also Salim Salamah, ‘Starving the Palestinian Yarmouk Camp,’ Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 28 April 2014.

10. Max J. Rosenthal, ‘Syrian Activist Forced from Hometown Pledges to Keep Publicizing Atrocities’, The Huffington Post, 3 August 2014.

11. Interview transcript at, ‘Syrian Activist on Ghouta Attack: “I Haven’t Seen Such Death in My Whole Life”’, Democracy Now!, 23 August 2013.

12. See Hans Hoyng and Christoph Reuter, ‘Assad’s Cold Calculation: The Poison Gas War on the Syrian People,’ Spiegel Online International, 26 August 2013.

13. Ibid. The regime’s use of gas followed the pattern of steady escalation already remarked upon. The use on a much smaller scale of chemical cocktails, sometimes including low levels of sarin, had been reported in the previous months. A Le Monde correspondent reported that ‘gas attacks occurred on a regular basis’ in Jobar in April 2013. see Jean-Philippe Remy, ‘Chemical Warfare in Syria’, Le Monde, 27 May 2013.

14. Interview with authors, December 2014.

15. Interview with authors, December 2014.

16. For barrel bombs – cheap concoctions of explosive and shrapnel tipped from planes or helicopters – see for example: www.hrw.org/news/2014/07/30/syria-barrage-barrel-bombs (accessed September 2015).

17. RYK’s June 2013 visit to Kafranbel. See Robin Yassin-Kassab, ‘Syria: Life in the Rebel Strongholds’, The Guardian, 14 August 2013.

Copyright © 2016 Pluto Books. All rights reserved. Reproduced by permission of Pluto Books. No further reproduction allowed without the written permission of the publisher.

Source Article from http://mondoweiss.net/2016/05/excerpt-syrians-revolution/

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

May 11th, 2016

May 11th, 2016  Awake Goy

Awake Goy

Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: