HSBC Bank and the world’s oldest Jewish drug cartel

HSBC’s core values are under scrutiny. The bank has been implicated in one scandal after another, and the current leadership claims to be wanting to restore the bank’s reputation. But what reputation do they aim to restore? Is it the airbrushed version of a bank rooted in “Scottish banking principles”, or is it an altogether darker reputation reflecting HSBC’s original role as a source of funding for the giant trade of opium into the Chinese markets in the nineteeth century? As one blogger, based in Rochester, USA, put it in 2013: “When HSBC executives were caught late last year financing the Mexican and other drug cartels, they were returning to the company’s historic roots.”

HSBC’s core values are under scrutiny. The bank has been implicated in one scandal after another, and the current leadership claims to be wanting to restore the bank’s reputation. But what reputation do they aim to restore? Is it the airbrushed version of a bank rooted in “Scottish banking principles”, or is it an altogether darker reputation reflecting HSBC’s original role as a source of funding for the giant trade of opium into the Chinese markets in the nineteeth century? As one blogger, based in Rochester, USA, put it in 2013: “When HSBC executives were caught late last year financing the Mexican and other drug cartels, they were returning to the company’s historic roots.”

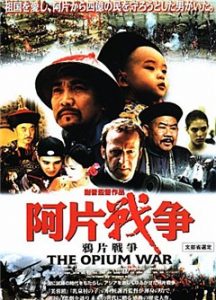

As this article from Le Monde Diplomatique explains, HSBC was founded after the second of the Opium Wars, by which time the trade was already well established. The founders included several opium traders who recognised the profitable banking opportunities presented by the new market. As Le Monde Diplo explains:

Another Scotsman, Thomas Sutherland, had joined P&O. He devoted his career to the company, worked on the construction of new wharves in Hong Kong and became the Hong Kong superintendent of P&O as well as the first chairman of Hong Kong and Whampoa Dock in 1863. Opium made up 70% of maritime freight from India to China, where it was sold to the Chinese by British compradores, despite all efforts by the Chinese authorities to stop it.

Sutherland understood that the time was right for a commercial bank. In 1865 he and a few others founded the Hong Kong and Shanghai Banking Corporation. The board was chaired by Francis Chomley, and included the remarkable Thomas Dent, founder of Dent & Co. In 1839 a senior Chinese government official, Lin Zexu, known for his competence and moral standing, issued a warrant for Dent’s arrest in an attempt to close his warehouses, which infringed the Chinese ban on opium. That helped trigger the first opium war, which ended in August 1842 with the unequal treaty of Nanking.

After the second opium war (1856-60), the British and French imposed territorial concessions under foreign administration, the opening of Chinese ports to foreign trade and the legalisation of the opium trade. When Sutherland began the Hong Kong and Shanghai Banking Corporation, the conflict had been over for five years. The Chinese characters in the transliteration of its name are auspicious, and can be understood to mean gathering wealth.

HSBC’s first wealth came from opium from India, and later Yunan in China.

Winston Churchill famously wrote that history is written by the victors, which might explain why so little attention is paid in Britain to the infamous Opium Wars of the nineteenth century, which saw the Brits using their superior naval power to open up ‘free trade’ with China. Opium — sourced initially from India — was by far and away the largest product traded by British merchants in return for Chinese silks, tea and porcelain. Facing understandable resistance from Chinese Emperor Tao Kuang and Lin Tse-hsu, his governor-general of the Liang Hu vice-regency, who was determined to stifle opium trade in his province, the British merchants resorted to violence to destroy the Chinese ability to impose their own laws and social protections. As Rolling Stone’s Matt Taibbi put it:

If you’re rusty in your history of Britain’s various wars of Imperial Rape, the Second Opium War was the one where Britain and other European powers basically slaughtered lots of Chinese people until they agreed to legalize the dope trade (much like they had done in the First Opium War, which ended in 1842).

In light of the British addiction to Chinese exports . . . opium was the only commodity that saved the British balance of payments with Asia from ruinous deficit. Marchant argues that mid-century British merchants in China believed that a ‘just war’ should be fought to defend progress. In reality the British leaders of the opium trade through the 1830s and 1840s were far more interested in protecting their drug sales in order to fund lucrative retirement packages (one of their number, James Matheson, used such profits to buy a seat in Parliament and the Outer Hebridean island of Lewis).

For how much of the time since its inception has drugs money run through HSBC’s veins? You decide.

War on drugs is just a hoax.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

July 27th, 2017

July 27th, 2017  Awake Goy

Awake Goy  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: