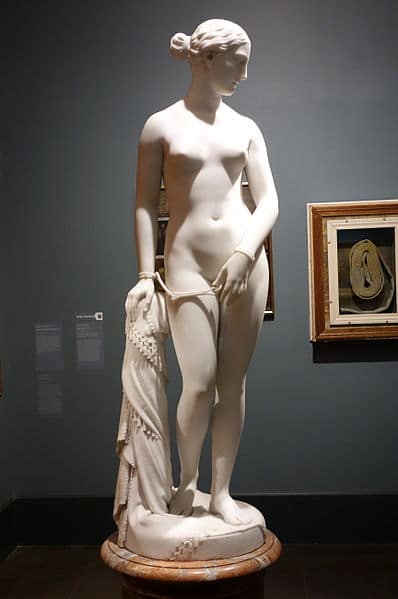

The iconic statue named the “Greek Slave,” created by the US sculptor Hiram Powers represents the incredible but true story of one of the more horrific chapters in Greek history, after a girl from Psara was captured in one of the battles of the Greek War of Independence.

The young girl, named Garifallia Michalbei (Γαρυφαλλιά Μιχάλβεη), went on to not only survive but to serve as an emblem of the abolitionist movement in the United States.

Garifallia, who was rescued from captivity by the American Consul in Smyrna, went on to be portrayed in paintings, but most notably of all she was depicted in a marble sculpture which is known as one of the finest sculptures ever created by an American.

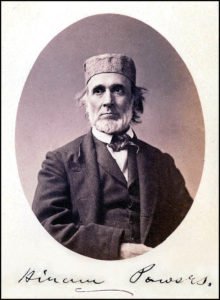

“The Greek Slave” was created by the sculptor Hiram Powers. One of the best-known and critically-acclaimed American artworks of the nineteenth century, it is among the most popular American sculptures in history.

Among many other things, hers became was the first publicly exhibited, life-size, American sculpture depicting a fully nude female figure — which was instrumental in evoking great sympathy for the Greek people as they emerged from their years of oppression, as well as for American slaves, who were still in bondage at the time.

The first marble version of the sculpture, which was completed by Powers’ studio in 1844, is now in Raby Castle in England.

Little Garifallia Michalbei, who had been captured during the destruction of Psara after the deaths of her parents, ended up in a slave market in Izmir (Smyrna). Joseph Langdon, the American Consul in Smyrna, saved her from a horrible fate by ransoming her and sending her to Boston to live with his family for the rest of her life.

Langdon’s rescue of Garafallia is described by one of his descendants, Louise Langdon van Agt, in her manuscript “The Humbler Bostonians,” part of the collections of the New England Historic Genealogical Society.

Real story of “The Greek Slave” touched Americans deeply

Author Harriet Beecher Stowe, in her 1854 book “The Key to Uncle Tom’s Cabin,” alludes to Garafallia by writing “I was in Smyrna when our American consul ransomed a beautiful Greek girl in the slave-market. I saw her come aboard the brig ‘Suffolk,’ when she came on board to be sent to America for her education.”

The story of Garifallia, who is buried in the historic Mt. Auburn cemetery in Massachusetts, touched America deeply and sparked sympathy for the abolition of slavery in America.

The fascinating details of the life of Garifallia can be found on the website of Professor Manolis Paraschos, who has done extensive work highlighting the many historical figures which connect Greece to Boston.

There will also be more news about the life of Garifallia toward the end of 2021 by British historian Mark Mazower, according to Greece’s Consul in Boston, Stratos Efthymiou.

Five more full-sized versions of the statue in marble were reproduced for private patrons, based on Powers’ original model, along with numerous smaller-scale versions. Copies of the statue were displayed in a number of venues around Great Britain and the United States; it quickly became one of Powers’ most famous works, and held great symbolic meaning for some American abolitionists, inspiring an outpouring of literary works.

Garafilia Mohalbi was born in 1817 to a prominent family on the island of Psara (Ψαρά). Her parents and siblings were killed in the 1824 Psara massacre by the Turks. There are many stories about exactly how she had managed to survive, but it is certain that in 1824 she had found herself working as a slave to a Turkish family in Smyrna.

At a bazaar in 1827, Garifallia had the great fortune to meet American merchant/consul Joseph Langdon and begged him to rescue her from her plight. He quickly ransomed the lovely Greek girl and promptly sent her off on a steamship to his Boston family, who welcomed her with open arms.

Accepted as one of the family as soon as she arrived, Garafallia thrived in her new surroundings, attending the Ursuline Convent School in Charlestown; however, at the age of thirteen, she began showing signs of suffering from tuberculosis and she passed away on March 17, 1830.

Her statue depicts a young woman, nude, bound in chains; in her right hand she holds a small cross on a chain. Powers himself described the subject of the work with these words:

“The Slave has been taken from one of the Greek Islands by the Turks, in the time of the Greek revolution, the history of which is familiar to all.

“Her father and mother, and perhaps all her kindred, have been destroyed by her foes, and she alone preserved as a treasure too valuable to be thrown away.

“She is now among barbarian strangers, under the pressure of a full recollection of the calamitous events which have brought her to her present state; and she stands exposed to the gaze of the people she abhors, and awaits her fate with intense anxiety, tempered indeed by the support of her reliance upon the goodness of God.

“Gather all these afflictions together, and add to them the fortitude and resignation of a Christian, and no room will be left for shame.”

This passage was from the article “The Greek Slave,” in Uncle Tom’s Cabin & American Culture, University of Virginia, 1998-2012, retrieved 4/5/2017.

“Superior to suffering, raised above degradation”

When Garifallia’s statue was taken on tour in 1847 and 1848, Miner Kellogg, a friend of the artist and manager of the tour, put together a pamphlet to hand out to exhibition visitors. In it, he provided his own description of the piece:

“The ostensible subject is merely a Grecian maiden, made captive by the Turks and exposed at Istanbul, for sale. The cross and locket, visible amid the drapery, indicate that she is a Christian, and beloved.

“But this simple phase by no means completes the meaning of the statue. It represents a being superior to suffering, and raised above degradation, by inward purity and force of character.

“Uncompromising virtue, or sublime patience”

“Thus the Greek Slave is an emblem of the trial to which all humanity is subject, and may be regarded as a type of resignation, uncompromising virtue, or sublime patience.”

Powers held that the young woman was a perfect example of Christian purity and chastity, because even in her unclothed state she was attempting to shield herself from the gaze of onlookers.

Additionally, he said, her nudity was of course no fault of her own, but was caused by her Turkish captors, who stripped her to display her for sale. So well did this resonate with the public that many Christian pastors would exhort their congregations to go and see the statue when it was displayed.

A symbol of the inhumanity of slavery

Abolitionists began to take the piece as a symbol, and the representation of Garifallia as a slave was the subject of a poem by John Greenleaf Whittier. The statue also inspired a famous sonnet by Elizabeth Barrett Browning called “Hiram Powers’ Greek Slave.”

In 1848, while walking through Boston Common, abolitionist Lucy Stone stopped to admire the statue and broke into tears, seeing in Garifallia’s chains the symbol of man’s oppression of the female sex. From that day forward, it was said, Stone included women’s rights issues in her speeches.

An Englishman purchased the first of the large marble versions of “The Greek Slave” (now at Raby Castle), and it was exhibited publicly in London in 1845 at Graves’ Pall Mall.

In 1851, it was featured by the U.S. at The Great Exhibition in London, and four years later was shown in Paris.

The second version of the statue was purchased by William Wilson Corcoran in 1851, and entered into the collection of the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C.; with the 2014 dispersal of the Corcoran collection, the statue was acquired by the National Gallery of Art in Washington.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

March 24th, 2021

March 24th, 2021  Awake Goy

Awake Goy  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: