There is no doubt that the Ancient Egyptian civilization is filled with wonders and mysteries beyond our comprehension. An exceptionally old culture that reaches far back to the early dawn of man’s advancement, Egypt left behind it many man-made wonders. From the enormous pyramids, the giant statues, and the sprawling mortuary temples, their monuments are many and glorious.

While some of these are easy to understand, study, and explain, others remain an absolute mystery. One such enigma is the so-called “Disc of Sabu”, a curious stone object that almost defies all logic. Over the years, many odd theories arose have arisen in an attempt to uncover its true purpose.

The Tomb of Prince Sabu

Anyone visiting the sprawling museum of antiquities in Cairo will be awed by the wealth of Ancient Egyptian treasures contained inside it. From the famed treasures found in the Tomb of Tutankhamun, to the pharaonic statues and well-preserved mummies, this museum is the number one stop for all lovers of this ancient culture. But while you will be dazzled by these popular treasures, one curious item can be easily overlooked. The Disc of Sabu.

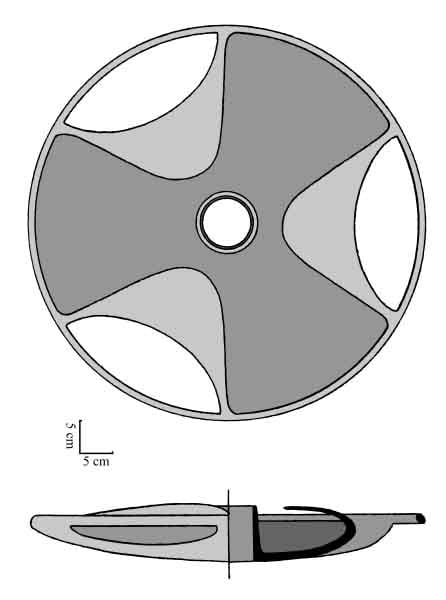

This odd item is circular in shape and measures roughly 610 millimeters (24 inches) in diameter and roughly 104 millimeters (4 inches) in height. It was discovered in 1936 by a renowned British Egyptologist, Mr. Walter Bryan Emery, and has been dated to the earliest periods of Ancient Egypt.

Emery devoted his career to excavations in the Nile River valley, and between 1935 and 1939 he conducted numerous surveys and digs in the burial grounds of Saqqara. The resting grounds of many high-status individuals from the early dynastic period, Saqqara is one of the oldest and largest necropolises from Ancient Egypt.

The Necropolis at Saqqara (Jose Javier Martin Espartosa / CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 )

Of course, digging in Saqqara yielded many important and valuable items, but none so odd as the Disc of Sabu. Emery discovered it while excavating the tomb of Prince Sabu, a First Dynasty governor and the son of the famed Pharaoh Anedjib. The latter was the fifth ruler of the First Dynasty, and succeeded the powerful Pharaoh Den.

Sadly, little is known of Anedjib’s son, Prince Sabu. He did not succeed his father on the throne, but still received an honorable burial at Saqqara. History does not record a lot of details about the dynastic relations in the First Dynasty, so we may never know of Sabu’s fate, his exact role in the court, or the political events of that time. Emery writes that Sabu was likely a high official and an administrator of a province, both during the reigns of Pharaoh Den (likely his grandfather), and his father Anedjib.

The Mysteries Beneath the Sands of Saqqara

The Mastaba (tomb) of Prince Sabu was discovered on the very edge of the plateau in the northern part of Saqqara. It was situated roughly 1.7 kilometers (1.1 miles) north of the iconic Stepped Pyramid of Djoser . Designated as “Tomb 3111”, it was excavated by Emery on January 10th, 1936.

The tomb consisted of seven funerary chambers, each strewn with assorted grave goods. The largest room held the body of Prince Sabu, which was accompanied by many funerary items. Most of these were nothing out of the ordinary – animal bones, flint implements, pottery vessels, ivory items, stone bowls. But one item stood out like a sore thumb: Emery discovered a curious disc, broken into numerous pieces.

The Disc of Sabu (Gretarsson / Public Domain )

Once painstakingly re-assembled, the Disc of Sabu intrigued many leading Egyptologists. The disc-shaped object resembles a round-bottomed bowl and has three extremely thinly carved, curving lobes at roughly 120 degree intervals around the bowl’s periphery. These lobes are separated from the rim by three biconvex holes.

In the center of the disc is a thin tube, roughly 10 centimeters in diameter. The object is constructed of metasiltstone, elsewhere referred to as schist. This is a porous, fragile rock that would be extremely difficult to carve – especially in such delicate detail.

Schist is comprised of coarse grains and characterized by elongated minerals in marked layers. It has the propensity to flake when worked, and can be crushed very easily when tools are applied to it. So here we have our first mystery: how was the disc carved in such fine detail?

When asking this question, we need to consider the age of the disc. Prince Sabu’s tomb is dated to circa 3,000 BC, making the disc at least 5,000 years old! It is believed that the tools used back then were made of stone and copper, which would make fine craftsmanship quite challenging, if not impossible, especially on such a fragile material as schist stone. Somehow, the Disc of Sabu seems out of place in a tomb of a First Dynasty noble.

An Ancient Egyptian Puzzle

The next mystery is the purpose of this object. Over the years, many convincing theories surfaced. Almost immediately following its discovery, the disc was “dismissed” as being a “vase” or “incense burner” , or simply a trivial decorative or ceremonial item. But many believe that this is far, far from the truth. One glimpse and just the basic knowledge of mechanics and engineering offers a wholly different interpretation – this disc could be a part of a mechanism.

There are marked similarities between the disc and a modern pump impeller (Asurnipal / CC BY-SA 3.0 )

One resourceful amateur historian may have solved the mystery. Armed with a 3D printer, this person created an accurate replica of the disc of Sabu in an attempt to prove his own theory: the disc was an ancient “impeller”, a part of a centrifugal pump. When placed in a housing and propelled at high speed via the small shaft at its center, the disc was extremely efficient at displacing water.

Furthermore, when propelled without a housing to direct the displaced water, the disc creates a powerful vortex. Observing these recorded experiments makes one thing clear: the curiously folded lobes and a slightly concave shape of the disc are there for a purpose. Thanks to the intricately carved details, the disc is able to displace water with ease, and is seemingly a crucial component of a water pump mechanism.

One fact supports this theory: Ancient Egypt depended on irrigation. Later in their history they perfected water management through basin irrigation, a process that allowed them to control the rise and fall of the river. Thus they managed to maximize their crops and boost their agricultural capabilities. So, why should it be odd to consider that they made attempts at creating an advanced design that would help them irrigate land quickly and efficiently?

An even older clay object dated to the Predynastic Naqada II period (3650 – 3300 BC) is oddly similar to the disc of Sabu. This object shows three “snakes” leaping up from the center of a disc that looks extremely similar to the Sabu disc, complete with the central shaft and the three biconvex holes. Could this clay object represent three water spouts being propelled from the disc? It seems very likely.

Proof of Ancient Astronauts?

But schist does not seem a strong enough material for a pumping mechanism. This suggests something else: were craftsmen from the First Dynasty of Egypt attempting to recreate an older object using the tools and materials available to them, an object they perhaps did not completely understand?

Many theories suggest that the disc of Sabu is just a schist stone replica of an original item made from metal. It is even suggested that the object was discovered amongst the remnants of an older, more advanced civilization, one that preceded the earliest history of Ancient Egypt.

The renowned Swiss author, Erich Von Däniken , is one of the leading proponents of the theory that extraterrestrials or superior, advanced civilizations influenced early humans. He suggests that the Disc of Sabu was an Egyptian stone copy of an internal component from an extraterrestrial ship’s hyperdrive, or more simply a stone model of a flying saucer . Others likened the disc to the advanced light-rimmed flywheels that were developed in the 1970’s by Lockheed missile engineers, and there are indeed plenty of similarities.

Does the Disc suggest alien contact with Ancient Egypt? ( Matrioshka / Adobe Stock)

Some however have proposed a much simpler role for the disc. They state that the three lobes were used to hold strands of silk or rope: when the disc was spun, it would weave the three strands into one, creating twine and thicker ropes. This theory is often dismissed as simply too straightforward: the Egyptians would not go to such extreme lengths to create the disc just to weave fibers when other methods were available quite early on.

There are other theories, some more extreme than the others. One French author suggests that the Disc of Sabu is just one of many that were an integral part of an early “factory”. This complex theory explains how the Ancient Egyptians manufactured Sodium Carbonate within pyramids using advanced systems and technologies.

As can be seen, a lot of proposals simply swerve into the realms of the impossible, and seem more based on wish-fulfilment than sound archaeology. Ancient hyperdrives, factory complexes, steering wheels, and other unlikely suggestions are simply impossible to prove.

Certainly More than a Vase

On the other hand, mainstream science has a suspicious tendency to dismiss every suggestion that the disc is part of a mechanism. Mainstream archaeology considers the disc to be an incense burner, or – bluntly – a vase.

Going to such extreme lengths to polish and shape the super-delicate schist stone into such a complex form simply to create a “vase” seems, on the face of it, unlikely. Even the process used to create the disc is difficult to explain, given its age. But, if we accept the fact that this is something craftsmen of the First Dynasty were able to create with the tools at their disposal, the question still remains: for what purpose? It seems clear that the disc of Sabu was part of something complex.

Schist was a popular choice for funerary carvings through Ancient Egypt (Daderot / Public Domain )

Walter Bryan Emery made note of his discovery in his Great Tombs of the First Dynasty , mentioning it as simply “a container in the form of a schist bowl.” He later mentioned it again in his work Archaic Egypt , where he described it as a “cachivache” – a knick-knack or trinket, a gadget.

However, several sources point to the fact that he was well aware of the problem it posed in scientific circles, where it was described “as a small hole that threatens to become a much larger one”. It is perhaps, for this reason, that the Disc of Sabu is often overlooked in scholarly literature. In fact, little is known at all about Prince Sabu, his tomb, or his peculiar disc.

Ancient Doesn’t Mean Primitive

In the end, it remains entirely possible that the Disc of Sabu was a crucial part of a more advanced design, one likened to a water pump. Considering the fact that the experiments using a disc replica were highly successful in that role, it could certainly function as one.

Ancient Egypt was highly dependent on irrigation to survive in the desert ( dejank1 / Adobe Stock)

With an adequate housing, water outlet, and means of propulsion, the Disc of Sabu could have easily displaced large amounts of water, quickly and efficiently. And given the need for irrigation in Ancient Egypt , the pieces of the puzzle quickly seem to fall into place. Given how unusual the design of the disc is, and given how useful a pump of this kind would be, it seems beyond coincidence that the disc would not be used for that purpose.

Perhaps it is time that we looked at the early Egyptians from a different perspective. Even though Prince Sabu lived 5,000 years before present, it doesn’t mean he and his contemporaries weren’t able to observe the world around them and come up with logical and ingenious solutions to the problems of their time. Even so, plenty of aspects about this disc cannot be easily explained, which leaves a lot of questions unanswered.

Top image: The Mysterious Disc of Sabu. Source: Christian Hart / Public Domain

By Aleksa Vučković

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

August 1st, 2021

August 1st, 2021  Awake Goy

Awake Goy  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: