In 2000, Rabbi Marvin Hier held a dinner in Los Angeles for the Simon Wiesenthal Center, the anti-Semitism monitor and Jewish advocacy group he leads. As the evening drew to a close, Hier handed out baseball caps with “Winnick Institute” written on the front: the name of the tolerance museum the SWC was planning in Jerusalem’s French Hill neighborhood.

Unlike the Los Angeles Tolerance Museum, Hier said, the Jerusalem one would not touch on the Holocaust, but would look to the future.

“In the 20th century, the biggest issue was the external threat,” Hier told the Los Angeles Times at the time. “There were wars, there was the Holocaust. But most historians and philosophers think that in the 21st century, the most important question will be: ‘Can we live with each other?’ The Winnick Institute Jerusalem will focus on the great internal question.”

The museum, he said then, would be open within five years.

Twenty-one years later, after endless rounds of court battles, public relations fights, architectural squabbles, redesigns and other delays, the Museum of Tolerance Jerusalem is finally getting ready to open its doors… in 2022.

Police on horseback ride by the Museum of Tolerance Jerusalem on April 5, 2021. (Joshua Davidovich/Times of Israel)

The name Winnick (for fiber-optic magnate Gary Winnick, whose firm went bankrupt in 2002) isn’t the only thing that’s changed. The price tag has ballooned from $120 million in 2000 to $270 million. And the museum is now in central Jerusalem, atop a 1,000-year-old Muslim cemetery, a move that has brought no small amount of controversy to a project that was meant to be a uniting force and has sparked questions about whether the Tolerance Museum, or MOTJ, is itself tolerant.

The museum’s hulking white home is already an imposing presence, sitting adjacent to Independence Park and the Mamilla quarter. The SWC says the museum, which includes several underground tiers, will cover some 14,000 square meters (just over 150,000 square feet). That would make it the second-largest museum in the country, nearly four times the size of Yad Vashem and smaller only than the flagship Israel Museum, according to available data on exhibition space.

According to Hier and Richard Trank, who is responsible for content at the center’s Tolerance Museum in Los Angeles and the new one in Israel, the building in downtown Jerusalem will comprise a Children’s Museum and a general museum. The latter will incorporate two exhibitions: A People’s Journey, looking at the past, and a so-called Social Lab, contemplating the present and future.

Artist’s impression of the front of the new Museum of Tolerance, Jerusalem. (Simon Wiesenthal Center)

In addition, there will be two theaters, an international conference center, a grand hall, an indoor/outdoor café, a gift shop, a library (including a display of special archival letters), classrooms, a public plaza, a sunken 1,200-seat outdoor amphitheater built around the remains of a Roman aqueduct, and underground parking.

Inside the exhibit spaces, the museum’s backers promise a new, cutting-edge museum experience, along with a lavish sprinkling of Hollywood style.

Rabbi Marvin Hier, founder of the Simon Wiesenthal Center, delivers a blessing at the inauguration of US President Donald Trump, January 20, 2017. (YouTube screen capture)

Though named for Simon Wiesenthal, a legendary Nazi hunter who was not directly involved with the center, the SWC is inseparable from Hier, its larger-than-life founder and leader.

The center prizes its place as part of the Tinseltown ecosystem, hosting movie stars and other celebrities. Photographs supplied by the center for this article featured well-known actors and other VIPs, and Hier, like many fundraisers, is no stranger to hobnobbing with celebrities.

The SWC runs its own movie outfit, Moriah, which is headed by Trank and focuses on documentaries. At one point in an interview Hier and Trank gave to The Times of Israel, Trank used Hier’s Hollywood cachet to defend him against charges of partisanship for having delivered an invocation at the 2017 inauguration of US president Donald Trump: “Explain to me why [former Israeli president] Shimon Peres spent the last year of his life with me and [Hier], doing interviews about his life, and why George Clooney narrated the movie and was our honoree for our annual event?”

California dreaming

Some elements of the Jerusalem museum will be borrowed from or inspired by the SWC’s Museum of Tolerance in Los Angeles, which opened in 1993 with the mission of combating hate by educating visitors about various forms of prejudice and discrimination, with a focus on anti-Semitism and the Holocaust.

The LA museum, currently closed due to the pandemic, has hosted more than 7.5 million visitors, including over 3 million youths and schoolchildren. Some 235,000 adults have gone through diversity training programs it has hosted in criminal justice and education. It has also positioned itself as part of the Hollywood scene, hosting movie stars and other celebrities for events.

A concert for United Hatzalah at the Museum of Tolerance Jerusalem in August 2019.

Many of the exhibits are centered on experiencing ideas rather than objects, and some of the approaches pioneered in LA are being brought to Jerusalem, including the Social Lab, where visitors will be challenged to confront various ideas and prejudices.

In Los Angeles, part of the lab took the form of a 1950s-themed diner called the Point of View Cafe, but it is set to be upgraded there and in Jerusalem by the LA-based Yazdani Studio, Trank said.

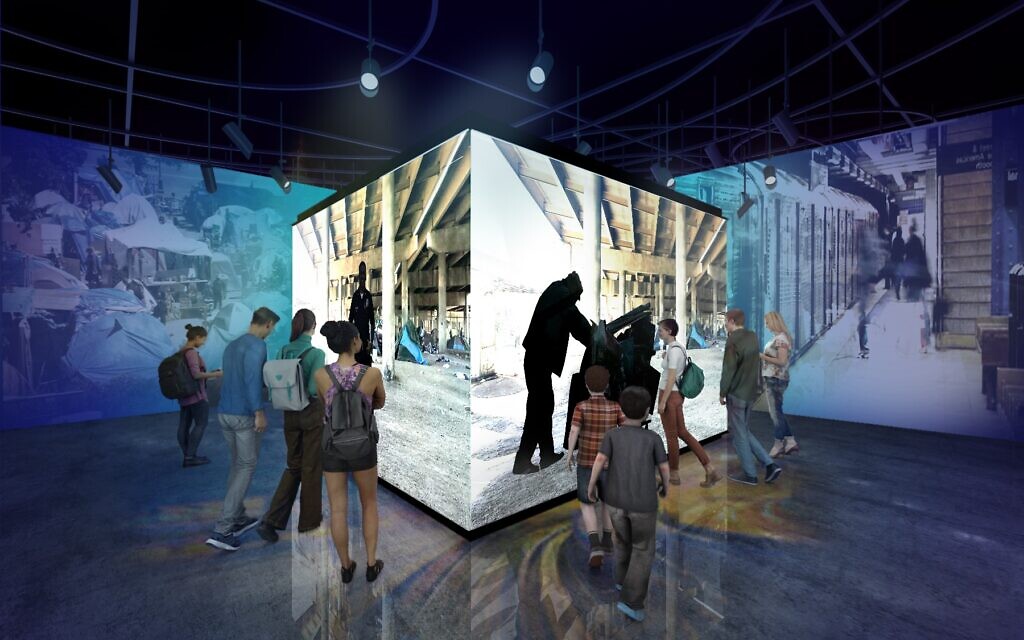

“We’ve taken this into the 21st century with a massive four-sided glass cube, with a different point of view about particular issues on each side,” he said. “In LA, it will deal with issues such as bullying, homelessness, the pandemic, policing and LGBTQ, with characters giving different points of view. That concept will be in the Social Lab in Jerusalem too, [where] it will look at the experiences of Israel, of Israelis and Palestinians, Muslims, Jews and Christians, Sephardi and Ashkenazi, religious and secular.”

Artist’s rendering of the Point of View exhibit planned for the LA Museum of Tolerance which will also feature at the Museum of Tolerance Jerusalem, with different content. (Simon Wiesenthal Center)

The lab will also include what the museum calls a Forum, where visitors explore an issue via dialogue and then vote on a solution, and a Global Crisis Center, which will have visitors navigate a pressure situation and see what the various consequences of their actions might be.

“It’s based on real things, like the pandemic,” Trank said.

Like the Los Angeles museum, MOTJ will feature an exhibit about the young Dutch Holocaust victim and diarist Anne Frank. But the Jerusalem center will also focus on Israeli history at a station about the Jewish aspiration to return to Zion.

Artist’s rendering of the Forum exhibit planned for the LA Museum of Tolerance which will also feature at the Museum of Tolerance Jerusalem, with different content. (Simon Wiesenthal Center)

This will form the climax of a broader exhibition about key Jewish values, such as faith, education, charity and community, that have kept the Jewish people together and enabled them to survive.

The museum will also feature lighter subject matter, such as an exhibit exploring comedy and humor and a look at Israel’s relationships to famous artists and performers such as Leonard Bernstein and Frank Sinatra, The Times of Israel was told.

‘Philanthropic imperialism’

One thing the museum is not supposed to have is Holocaust-related content, setting it apart from the Los Angeles center. Indeed, when plans for the museum were first coming together over two decades ago, the Yad Vashem Holocaust Memorial and Museum made sure that the government conditioned its giving land for the Tolerance Museum on an agreement not to cover Holocaust-related issues.

“It appears to us that the establishment of a museum of tolerance in Israel is unnecessary and it is most certainly unacceptable and irregular for the State of Israel to place land at the disposal of foreign nationals who do not represent any group but themselves within the Jewish people,” a Yad Vashem spokesperson told Haaretz in 1999.

Barbra Streisand touring Anne, an exhibition at the Museum of Tolerance, Los Angeles, in 2013. (Simon Wiesenthal Center)

A Yad Vashem spokesperson told The Times of Israel that it did not oppose the Museum of Tolerance but had held talks with the SWC to ensure it would not address the Holocaust. “Yad Vashem holds that there is no justification for another Holocaust center in Jerusalem, as Yad Vashem, the national Holocaust Remembrance Authority is already there. Since [the talks], Yad Vashem has received no additional information about the content of the Museum of Tolerance in Jerusalem.”

As for the rest of the content, both Hier and Trank said that SWC was consulting with Israelis and would be working with focus groups in both countries, but Hier indicated that Israelis would have limited input.

“If you’re asking whether the Israelis will have the final say on all the content, absolutely not. This is a world museum and we’re consulting with people all over the world. It’s the Museum of Tolerance in Jerusalem, meaning that we’re consulting with world Jewry and non-Jews,” he said.

Artist’s rendering of the Children’s Museum planned for the Museum of Tolerance in Jerusalem. (Simon Wiesenthal Center)

The exhibits in Los Angeles and Jerusalem are both being designed by the California-based Yazdani Studio, an architecture and design firm with projects around the world.

A spokesperson from the SWC declined to name who in Israel had been consulted on the project. “We work with and have been in touch with an array of Israeli consultants and institutions just as we were when we built the Museum of Tolerance in Los Angeles in 1993. These are working relationships, and at the appropriate time, with their permission, we will be going public, but we will not be doing so right now,” the spokesperson said.

Aerial view of the Museum of Tolerance Jerusalem under construction. The paved area behind is the Mamilla Pool, an ancient reservoir. (Dchaseb, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons)

A source involved in the Israeli museum sector, who asked not to be named, criticized what was said to be a lack of local buy-in for the project, accusing the museum’s backers of practicing “philanthropic imperialism.”

“Our country is full of talented people. Why do they think in LA that they’re better than us, that they can tell us what to do here?” this source asked. “Do they have a local curator? Local exhibit makers? If they think that they can preach tolerance to the natives in the craziest city on Earth, they don’t know where they’re living.”

If you’re asking whether the Israelis will have the final say on all the content, absolutely not

SWC refuses to talk about donors for the $270 million project, although Hier dropped a couple of hints when he talked about the Diamond Amphitheater outside, the Snider Theater, which seats nearly 400, and the Samson Theater, which accommodates 150. (Gordan and Leslie Diamond, Jay and Ed Snider, and Lee Samson are all on the SWC’s board of trustees, according to recent US tax filings.)

The museum’s opening date will depend on the completion of the Israel-relevant content of the exhibits, which Hier estimates will be within 12 to 15 months.

From right: George Clooney, Simon Wiesenthal Center 2020 Humanitarian Award Recipient and narrator of Moriah Films’ newest documentary, Never Stop Dreaming: the Life and Legacy of Shimon Peres, with Rabbi Marvin Hier, founder and dean, Simon Wiesenthal Center and Richard Trank, Writer/Director, Executive Producer, Moriah Films, who also oversees content for the Museum of Tolerance Jerusalem. (Simon Wiesenthal Center, 2018)

Finding the plot

In Hier’s telling, the genesis of the museum was in 1993, when late Jerusalem mayor Teddy Kollek visited the LA museum and was so impressed he asked Hier to build something similar in Jerusalem.

Faith, by Alexander Liberman, French Hill, Jerusalem. (Djampa, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons)

The first site considered was in French Hill, close to the Mount Scopus campus of the Hebrew University in the north of the city, where Alexander Liberman’s “Faith” statue stands today.

According to a Haaretz report at the time, Hier sought to be granted an expensive piece of land near the city’s German Colony to construct the museum, but Ehud Olmert, who succeeded Kollek as Jerusalem’s mayor, demanded that the SWC pay for it.

Instead, Olmert gave the SWC a large plot on the seam between Jerusalem’s city center and the Mamilla neighborhood, a former no-man’s-land that was in the early stages of redevelopment at the time. Even then, the parcel was a choice piece of land, next to Independence Park and across the road from the popular tourist stores and eateries of historic Nahalat Shiva. Today, it is even more so, with the city center continuing to hum and the Mamilla area’s tony shops and hotels a short walk away.

A man walks through a Muslim cemetery in the shadow of the under-construction Museum of Tolerance Jerusalem on April 5, 2021. (Joshua Davidovich/Times of Israel)

In 1999, SWC took on the LA-based Jewish architect Frank Gehry, who designed a mammoth building reminiscent of the sleek, swooping glass and steel structures foe which he has earned worldwide renown, including the iconic Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao and the Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles.

The site was rezoned and Gehry’s plans were approved in 2002, to the chagrin of many who saw megalomaniac madness in the glass, stone and titanium structure, clad in silver and blues, that appeared so estranged from its intended surroundings.

Architect Frank Gehry’s design for the Museum of Tolerance, Jerusalem. (Simon Wiesenthal Center)

Two years later, then-California governor Arnold Schwarzenegger visited to symbolically break ground on the site, though as it turned out, he was breaking open a Pandora’s box.

Once the Israeli Antiquities Authority began its usual pre-construction salvage dig to explore what was on and under the site, reports began to surface of graves being dug up and human bones being found.

Bones of contention

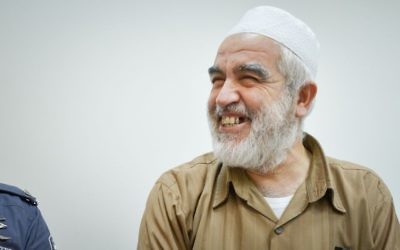

In 2005, the so-called Al Aqsa Association, affiliated with the now illegal Northern Branch of the Islamic Movement led by firebrand Sheikh Raed Salah, submitted a petition to the High Court demanding that the works be stopped on the grounds that constructing the museum would violate the sanctity of the cemetery.

The court suspended excavations in 2005, by which time around 400 out of an estimated 1,000 skeletons had been removed and taken in cardboard boxes to the Abu Kabir Forensic Institute in Tel Aviv in the hope that a Muslim religious figure could be found to rebury them.

The Mamilla pool and cemetery seen from the air in a photo taken sometime between 1928 and 1946. (Library of Congress/Matson Collection)

There are several precedents in which Muslim religious figures gave the green light for construction on the Mamilla graveyard, which once covered 138 dunams (34 acres).

Before the State of Israel existed, for example, lawyers for the grand mufti of Jerusalem, Haj Amin al-

In 1964, Jaffa’s Muslim Qadi Taher Hammad issued a ruling lifting the holiness from most parts of the cemetery to allow for the creation of Independence Park. Though he did not okay building there, a school, a parking lot and other buildings were later constructed along the cemetery’s northern end.

A Muslim grave next to the Museum of Tolerance Jerusalem on April 5, 2021. (Joshua Davidovich/Times of Israel)

Prof. Yitzhak Reiter, who has written several books and papers on the controversy, was approached by the SWC during the court case, and suggested that it offer the Islamic Movement a hall within the new museum that would show the history of the Muslim cemetery and would be headed by a Muslim Arab curator who could show people around.

“They didn’t like it, but were willing to let me try,” Reiter recalled, “but the people close to the Islamic Movement told me that Raed Salah would not accept any compromise. If the Muslims had been represented by more moderate figures, I think the Supreme Court would have ruled against the construction of the museum on that site.”

Leader of the northern branch of the Islamic Movement in Israel, Sheikh Raed Salah, arrives at the Rishon Lezion Magistrate’s Court on August 15, 2017. (Avi Dishi/Flash90)

Instead, in late 2008, the court ruled that construction could resume, noting that nobody had complained during the nearly 50 years that the site had functioned as a public parking lot.

At this point, the SWC, which had already spent $15 million, pressed on with building on the same site, rather than find a new one.

“There were all sorts of opportunities,” said Reiter, who teaches at Ashkelon Academic College. “They could have moved to another place — say, the museum compound in Givat Ram. It would have saved them a lot of trouble. But they’d already spent a lot of money before the case came to court. In hindsight, they couldn’t have done much because the Islamic Movement wouldn’t compromise.”

Prof. Yitzhak Reiter, who holds the Chair of Israel Studies at the Ashkelon Academic College. (Courtesy)

Gehry reportedly also refused to compromise on his design and quit in early 2010. He was replaced by Israeli architects Bracha and Michael Chyutin, who came up with the smaller and less flamboyant structure nearing completion today.

The Chyutins have since left the project and battled the SWC for seven years until they reached agreement on payment for the use of their plans. They were replaced by Aedas, an international firm, in cooperation with the Jerusalem architect Yigal Levy.

The Chyutins’ bridge-shaped design slashed the height of Gehry’s plan by nearly half and its square footage by two-thirds. The building comprises three above-ground levels and two underground ones, not counting parking levels further down.

View of the construction site of the Museum of Tolerance in Jerusalem on May 7, 2018. (Yonatan Sindel/Flash90)

The facade facing the city center is clad in an almost-white limestone, while a line of large glass windows looks out onto the green landscape of the park and remaining cemetery on the other side. A walkway beneath the bridged part of the building will connect the two sides. From the city side, the view southeast, including the iconic YMCA bell tower, is completely blocked off.

A view of the Museum of Tolerance Jerusalem, seen from the Nahalat Shiva neighborhood on April 5, 2021. (Joshua Davidovich/Times of Israel)

Hier noted that since the excavations began, the project was supervised by the Israel Antiquities Authority and the Tolerance Museum followed every instruction meticulously.

Illustrative: Rabbi Marvin Hier, discusses the historical accuracy of Mel Gibson’s film The Passion of The Christ, during a press conference at the Museum of Tolerance, in Los Angeles, Tuesday, February 24, 2004. (AP Photo/Stefano Paltera)

Museum officials hope that Arabs will visit the museum. The audio devices provided to visitors as they go through its exhibits will offer Arabic, as well as Hebrew and English.

Hier took pains to stress the SWC’s positive relationships with the Arab world. “The late King Hussein of Jordan visited our LA museum before Jordan recognized Israel and became a member and carried his museum membership card in his pocket,” he said. “We will use those connections with the Arab world in the Museum of Tolerance.”

Jordan’s late King Hussein and Queen Noor with Rabbi Marvin Hier, Simon Wiesenthal Center founder and dean, and a delegation, at the Holocaust section of the Museum of Tolerance Los Angeles, 1995. (Simon Wiesenthal Center.)

But to Reiter, and to others who expressed reservations privately, the idea of a museum dedicated to tolerance placing a massive edifice atop a Muslim cemetery, over the protestations of local Muslims, is the worst kind of irony. In this part of the world, sensitivities are raw, and symbolism of the past can exert a powerful force on the present.

“Maybe there would have been justification [for building on the graveyard] if, say, an emergency ward was to be built,” said Reiter. “But the big problem is that it’s a museum of tolerance. What tolerance do you show to the other, if you create a tolerance museum on a cemetery?”

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

April 18th, 2021

April 18th, 2021  FAKE NEWS for the Zionist agenda

FAKE NEWS for the Zionist agenda  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: