A new archaeological study in Japan, published in the August issue of Journal of Archaeological Science , has produced evidence supporting the idea that population growth can lead to an increase in warfare and other forms of violence. Academics who study the history of human warfare have identified population pressures as one root cause of mass killings, since they can lead to resource scarcities and land shortages. Now, pure archaeological research on skeletal remains from Japan’s Middle Yayoi period (350 BC-25 AD) has produced proof supporting this theory.

A Case Study: Japan’s Middle Yayoi Period (350 BC-25 AD)

To explore the connection between population growth pressures and violence, a team of archaeologists and anthropologists led by Professor Naoko Matsumoto from Okayama University studied skeletal remains and jar coffins collected from various archaeological digs on Japan’s Kyushu island . They concentrated on well-dated burials that took place during Japan’s Middle Yayoi period, which covers the years 350 BC to 25 AD.

This choice was made for two reasons. First, because past studies have revealed that violence on Kyushu increased during the Yayoi period, in comparison to the preceding Jomon period that ended in the year 350 BC. And second, because the original Yayoi people were farmers who actually came to Kyushu from the Korean Peninsula. And as they continued to move in alongside the native Jomon hunter-gatherers population and population density rapidly increased on the island of Kyushu.

These images from the recent study show evidence of violence in the cut mark on this Yayoi period man just above his right eye socket. ( Journal of Archaeological Science )

Past excavations had recovered significant numbers of Middle Yayoi burial jars from six separate micro-regions in the northern part of Kyushu. These areas have been identified as the Itoshima Plain, the Sawara Plain, the Fukuoka Plain, the Mikuni Hills, the Eastern Tsukushi Plain, and the Central Tsukushi Plain.

In each of these micro-regions, the Japanese scientists used the number of burial jars recovered to estimate likely population sizes (more burial jars recovered meant more people), and calculated population pressures by comparing population sizes with the availability of arable land (less farmland per person meant higher population pressure).

Various skeletal remains taken from Middle Yayoi digs had already demonstrated an obvious increase in violence during that time. By looking more closely at where exactly the traumatized skeletons were found, the Japanese scientists were able to make a comparison between population pressures and the frequency of violence in each of the six micro-regions.

The data they uncovered did reveal a correlation between population growth and violence, as they explained in their study that was published in the August 2021 issue of the Journal of Archaeological Science . In general, micro-regions with the highest frequency-of-violence levels were also found to be more greatly affected by high population pressure. The relationship was strongest in the Mikuni Hills region, which ranked at the top in both categories.

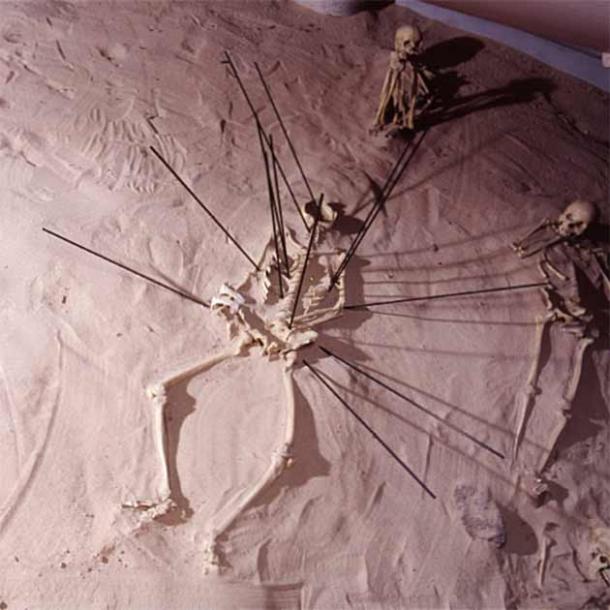

These rods are all pointing to places on this Yayoi period skeleton where violence was suspected based on the forensic details at these locations. ( National Museum of Nature and Science, Tokyo )

It must be noted, however, that the relationship didn’t apply in every instance. For example, while the Sawara Plain had one of the three highest levels of violence, its population pressure was relatively low. The researchers’ data showed that population increases could affect frequency-of-violence levels, but they didn’t establish that this was the only thing that might have had such an impact.

“I think that the development of a social hierarchy or political organization might also have affected the level of violence,” Professor Matsumoto said in a Okayama University press release introducing her team’s findings.

“We have seen stratified burial systems in which certain members of the ruling elite, referred to as ‘kings’ in Japanese archaeology, have tombs with large quantities of prestige goods such as weapons and mirrors. It is worth noting that the frequency of violence tends to be lower in the subregions with such kingly tombs. This suggests that powerful elites might have a role in repressing the frequency of violence.”

If this assumption is accurate, the reverse would also likely be true. In areas where powerful ruling elites were scarce, or didn’t have much influence over events, violence might be more likely to break out, even if population pressures were relatively modest.

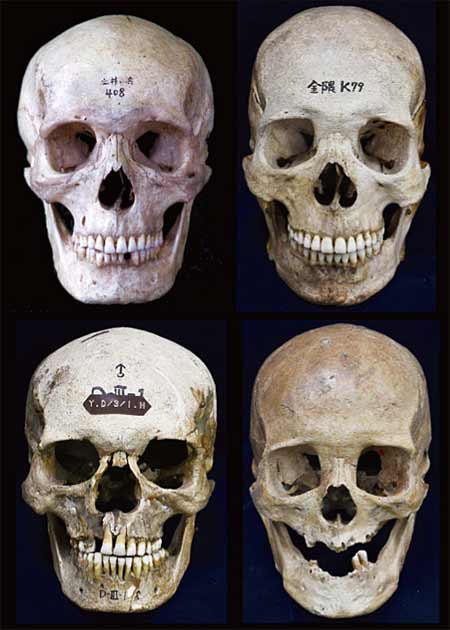

Analyses of the human skeletal remains excavated at the Middle Yayoi period Doigahama site (near Shimonoseki, Japan; the closest point on Honshu island to Kyushu island) showed that Yayoi people skulls (upper two) were relatively longer and flatter than those of the earlier Jomon people (lower two). ( National Museum of Nature and Science, Tokyo )

A Complex Problem with Complex Causes

There are reasons to be cautious about the conclusions of the Japanese researchers.

One issue is that they were relying on a relatively small sample size, confined to one time period in one location, to make what seem to be universal conclusions about the human condition. If future studies on this question find similar results that apply to different places and times, this would add more weight to their interpretation of the archaeological record.

Also, there may be alternative explanations that help explain why the Jomon-to-Yayoi transition was marked by an increase in violence.

Some academics believe that the transition from hunter-gatherer to agricultural societies caused tensions between and within groups that ultimately led to more violence and warfare. Others suggest that the development of new and more lethal weapons , and their introduction to new areas, is often enough in itself to cause an increase in violence.

Both of these theories are relevant to the situation on Kyushu 2,000 years ago, as Professor Matsumoto explains.

“The inhabitants of the Yayoi period practiced subsistence agriculture , in particular wet rice cultivation,” she said. “This was introduced by immigrants from the Korean peninsula, along with weapons such as stone arrowheads and daggers, resulting in enclosed settlements accompanied by warfare or large-scale inter-group violence. However, those living during the Jomon period were primarily pottery-makers who followed a complex hunter-gatherer lifestyle and had low mortality rates caused by conflict.”

There were likely multiple factors that explain why violence dramatically increased among people living on the Japanese island of Kyushu during the Middle Yayoi period. The study by Professor Matsumoto and her team has added to history’s understanding of what happened, by showing that population pressure can definitely play a causal role in the onset of warfare and mass violence. Their results will undoubtedly provoke further study of this relationship, and as evidence accumulates it will increase our comprehension of the root causes of violence in both the past and the present.

Top image: Skeletons from Japan’s Middle Yayoi period (300 BC-250 AD) found at the well-known Doigahama site, a stone’s throw east of Kyushu . A recent study by the Okayama University has revealed that hyper-violence was especially common in the Middle Yayoi period ( 350 BC-25 AD ) based on their analysis of north Kyushu skeletal remains. Source: National Museum of Nature and Science, Tokyo

By Nathan Falde

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

August 24th, 2021

August 24th, 2021  Awake Goy

Awake Goy  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: