The following essay is an extract from Stone Circles Explained by Stephen Childs, in which the author offers some original theories regarding the purpose of stone circles. Covering sites from around the world, including Gobekli Tepe, Stonehenge and Avebury, the book theorizes on the various reasons for why prehistoric stone circles were built. Here Childs will be exploring the Neolithic Gobekli Tepe site in Turkey, proposing that this famous site served the funereal needs of a wide area.

Understanding the 11,000-Year-Old Monumental Gobekli Tepe

Gobekli Tepe is located in Turkey, close to the Syrian border and to Harran, the traditional homeland of Abraham. Like some other sites in the area it is reckoned to be about 11,000 years old – more than twice the age of the pyramids and Stonehenge. The complex is on a hilltop, apparently remote from running water and from any sign of human habitation.

Gobekli Tepe consists of at least 20 adjacent stone circles 10 to 30 meters (32 to 98 ft) in diameter only four of which have so far been excavated. Archaeologists have speculated that this and other similar complexes in the area were the world’s earliest temples, which does not explain their primary purpose.

The circular pits of Gobekli Tepe, as seen from above. (Author provided)

The circular pits vary in size and in details. One feature that is common to all four slightly elongated circles is a pair of large T-shaped pillars which face each other in the center of each circle. These large pillars up to five meters (16 ft) tall would have supported timber platforms of about three by one meter (about 10 by 3.28 ft).

Corpses were placed on these platforms, inviting vultures and other meat-eating birds to de-flesh the bodies. Some ancient cultures believed high-flying carrion birds transported the flesh of the dead up to the heavens.

The central platforms would have been accessed by timber planking connecting them to a circle of timber lintels which rested on about a dozen stone pillars which were shaped like an inverted L, enabling the lintels to slightly overhang the circular pits, thus providing shelter and a little shade for mourners who were seated on low benching made of smaller stones which were built against the inner walls of the pit.

The walls were also built up with smaller drystone work between the pillars. These L shaped pillars were sculpted in quasi human form as guardians of the pit. They presumably represented either ancestors or divinities – there was little if any separation between these two categories in the prehistoric mind.

Corpses were placed on platforms discovered in the Gobekli Tepe stone circles, inviting vultures and other meat-eating birds to de-flesh the bodies. (Author provided)

Recreating the Dramatic Funerals of Gobekli Tepe

With a little imagination we can recreate the drama of a funeral at Gobekli Tepe 11,000 years later. The mourners descend a short flight of eight stone steps into the circular pit of the temple. They enter by a rectangular doorway cut through a great stone three meters square (9.84 ft). They sit around the walls of the pit on stone benches.

The deceased has been carried in with them and is seated in the place of honor, to join with the mourners in a “last supper” typically consisting of bread and gazelle meat. The corpse eats nothing despite being offered food and so, at the end of the feast, the mourners conclude that he is ready to pass into the spirit world.

It is just possible that ritual cannibalism was also practiced at Gobekli Tepe . Partially burned human bones with cut marks suggest de-fleshing, while bowls found on site may have been used to catch blood which could then be drunk so that family members might inherit the vital energies of the deceased.

Unwanted babies may also have been consumed in this way as was later done by the Carpocratians. Such rituals were not uncommon in ancient cultures and survive symbolically to this day in the ceremony of Christian communion. However, cannibalism at Gobekli Tepe is uncertain because this was not part of the subsequent Zoroastrian tradition.

Left: Rectangular doorway found at Gobekli Tepe, through which carnivores entered the pit to consume the corpse. Right: Portal stone located at Gobekli Tepe. (Author provided)

If not eaten, the corpse was carried up onto the central platform three meters (9.84 ft) above floor level where vultures would pick at it. Eventually the corpse would disintegrate and fall back down into the pit. When the mourners left the pit, their entry door was closed off and at the same time another adjacent rectangular doorway in the great entrance boulder was uncovered (above left). This gave access to an outer passageway within which carnivores had been confined. These then entered the pit and consumed what remained of the corpse.

Another portal stone (above right) was located low down in a wall at Gobekli Tepe . Its size, shape and position, coupled with the carvings of animals clearly indicates that it was an entrance designed for use by four-legged creatures and could easily be blocked off to contain them. The fact that a circular ring of lintels overhung the pits helped to ensure that animals could not escape.

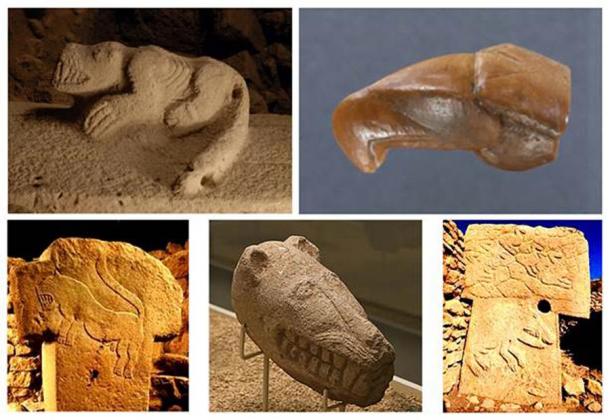

The pillars at Gobelki Tepe are inscribed with carvings of vultures, snakes, scorpions and several different kinds of four-legged carnivores with prominent teeth. Bone crushing hyenas consume 95% of their prey and are known to scavenge on human corpses. Foxes, jackals, hyenas, lions and wild boar were kept in the pits to finish off disintegrating carcasses and bones.

These carnivores became totem animals which were regarded as unclean and were not eaten by their keepers. To date, only fragments of human bone have been found at Gobekli Tepe . Sixty percent of bone fragments were of gazelle, which had presumably been consumed by mourners in the funeral feasts.

This (copy) pillar from Gobekli Tepe shows the headless corpse of an infant surrounded by vultures, snakes, a fox and a scorpion. (Author provided)

130 obsidian knives have so far been found at Gobekli Tepe . These may have been used to sculpt and inscribe stones, or alternatively for the purpose of butchering gazelles and corpses. The obsidian has been identified as coming from a number of volcanos spread over an extended area, so it seems likely that Gobekli Tepe served the funereal needs of a wide area. The multiplicity of circular pits suggests that quite a number of corpses might simultaneously have been in need of disposal.

Just a few miles away the village of Navali Cori, which was contemporary with Gobekli Tepe, is now submerged following the construction of a dam. Some of the houses there were found to contain depositions of human skulls and incomplete skeletons. It seems likely that these relics had been salvaged for domestic veneration following corpse exposure to vultures and scavengers in the “temples” at Gobekli Tepe. A carving with a matching severed head has been found at Gobekli Tepe .

Sky burials are still practiced in Tibet and Mongolia, as well as by the Parsis of Iran and India whose religion is derived from Zoroastrianism. The same methods were used by North American Indians in proto-historic times, which suggests that the practice is very ancient.

Carvings of flesh eaters found at Gobekli Tepe. (Author provided)

Gobekli Tepe in the Book of Daniel?

The pits at Gobekli Tepe were probably also used for the sacrifice of unwanted babies and to execute criminals and enemies, as well as for disposal of those who had died a natural death. It was perhaps in this place that the prophet Daniel had his well-known close encounter in the lions’ den. The Book of Daniel tells the story.

King Darius had come to power in Media around 522 BC and gradually built the expanding Persian Empire by defeating many local kings. His empire, which was sub-divided and ruled over by some twenty satraps or local governors, included the earlier Assyrian empire and what is now Syria, Turkey and Iran.

The prophet Daniel may have been one of the Jewish children taken into captivity in Babylon. He rose to the favored position of senior governor within the Persian Empire, probably within the province of Media. Writing around 450 BC the historian Herodotus indicated that Media was regarded as the highest-ranking nation in the empire. Media seems to be poorly defined, but it roughly comprised the upper part of Mesopotamia where Gobekli Tepe is located.

Lesser governors to set a trap for Daniel who persisted in the worship of the outlawed god of Israel. Darius had forbidden the worship of this deity and had decreed that anyone so worshiping should be “thrown into the lion’s den.” The king was bound by his own decree to carry out this sentence when Daniel’s religious observances were reported to him by jealous governors:

“So the king gave the order, and they brought Daniel and threw him into the lions’ den. The king said to Daniel, “May your God, whom you serve continually, rescue you!”

A stone was brought and placed over the mouth of the den, and the king sealed it with his own signet ring and with the rings of his nobles, so that Daniel’s situation might not be changed. Then the king returned to his palace and spent the night without eating and without any entertainment being brought to him. And he could not sleep.

At the first light of dawn, the king got up and hurried to the lions’ den. When he came near the den, he called to Daniel in an anguished voice, “Daniel, servant of the living God, has your God, whom you serve continually, been able to rescue you from the lions?”

Daniel answered, “May the king live forever! My God sent his angel, and he shut the mouths of the lions. They have not hurt me, because I was found innocent in his sight. Nor have I ever done any wrong before you, Your Majesty.”

The king was overjoyed and gave orders to lift Daniel out of the den. And when Daniel was lifted from the den, no wound was found on him, because he had trusted in his God.

At the king’s command, the men who had falsely accused Daniel were brought in and thrown into the lions’ den, along with their wives and children. And before they reached the floor of the den, the lions overpowered them and crushed all their bones…

So Daniel prospered during the reign of Darius and the reign of Cyrus the Persian.” (Daniel 6, New International Version)

Thanks to the layout at Gobekli Tepe it would have been possible to lower Daniel into the central pit whilst the lions were still restrained within the outer passageway. It seems likely that Darius had devised a plan whereby he complied with the letter of his own law, without risking the life of his valued servant. When Daniel was “miraculously” found to have survived a night in the “lions’ den” Darius had the excuse he needed to endorse the god of Daniel and to throw Daniel’s rivals into the central pit where they were immediately consumed by hungry lions.

Daniel in the Lions’ Den by Peter Paul Rubens. ( Public domain )

References to Ritual Exposure: Recycling Corpses at Gobekli Tepe

It is known that Darius the Great was a worshipper of Ahura Mazda the supreme deity of Zoroastrianism and this points us forward to the Parsis whose geographical origins were around Persia and whose religious root is also Zorastrianism. The earliest reference to Zoroastrian ritual exposure comes from the Histories of Herodotus (circa 450 BC) who described the rites as secret, but vaguely indicated that the corpse was dragged around by a dog or bird as part of the process.

The Byzantine historian Agathias described the Zoroastrian funeral at Mtskheta (Georgia) in 555 A.D. of the Sasanian general Mihr-Mihroe:

“The attendants of Mermeroes took up his body and removed it to a place outside the city and laid it there as it was, alone and uncovered according to their traditional custom, as refuse for dogs and horrible carrion .”

In the Parsi tradition circular towers or Dakhma were used until very recently for the disposal of corpses. These circular towers were built atop hills or low mountains in desert locations distant from population centers. Zoroastrian tradition considers a dead body to be unclean so there are rules for disposing of the dead as safely as possible. To preclude the pollution of earth or fire the bodies of the dead are placed on top of a dakhma and exposed to the sun and to scavenging birds. Thus, putrefaction with all its concomitant dangers is most effectively prevented.

Dakhmas have an almost flat roof, with the perimeter being slightly higher than the center. The roof is divided into three concentric rings. The bodies of men are arranged around the outer ring, women in the second circle, and children in the innermost ring. Once the bones have been bleached by the sun and wind, which can take as long as a year, they are collected in an ossuary pit at the center of the tower, where—assisted by lime—they gradually disintegrate.

The similarities between Parsi tradition and the physical evidence at Gobekli Tepe are so remarkable as to be beyond coincidence. In both cases we have:

- A hilltop location remote from human habitation.

- A circular complex consisting of up to three concentric rings.

- A central pit.

- Indications of a central elevated platform.

- Participation of vultures and carnivores.

There can be no doubt that the primary purpose of the complex at Gobekli Tepe and others like it was the recycling of corpses in a hygienic and environmentally friendly way. The layout of this prehistoric dakhma and its associated funereal practices has continued essentially unchanged for more than 10,000 years in the Parsi tradition.

Archaeologists and investigators seem not to have considered the possibility that a carnivorous zoo was maintained within the circular pits of Gobekli Tepe for disposal of corpses.

Said to be half bull and half man and kept in a labyrinth where he lived on a diet of sacrificial maidens, the Cretan legend of Theseus and the minotaur (Asterion) may also refer to a complex similar to that at Gobekli Tepe. ( Public domain )

The pits at Gobekli Tepe were filled in with rubble long ago, perhaps when a later phase of building was undertaken, or when other methods of corpse disposal became more popular. The epoch when Gobekli Tepe was first active was an age when humans were themselves largely carnivorous. It was succeeded by an age when agriculture emerged and became dominant, involving the annual regeneration of seed. This in turn led to veneration of cereal deities and hence to a belief in reincarnation or resurrection, encouraging humans to bury their dead in the expectation that their corpses would at some future date return to life like seeds of grain.

Ancient people seem to have believed that the human soul was translated into the body of the creature which ate the corpse. This explains the widespread portrayal of humans with animal or bird heads which we find venerated in Egyptian and other ancient traditions. The Buddhist notion that humans can reincarnate as animals or other creatures is rooted in the same idea.

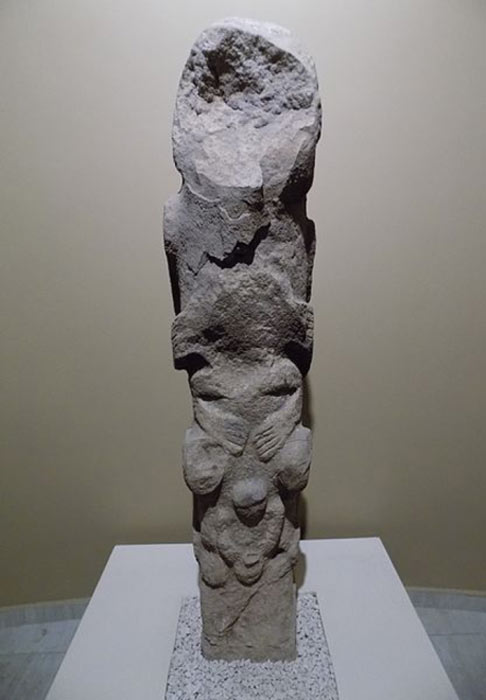

Stone totem pole discovered at Gobekli Tepe. (Author provided)

A stone totem pole measuring two meters (6.56 ft) tall has been found at Gobekli Tepe . It is damaged, but seems to show several organically connected beings, arising on top of each other. The uppermost creature is possibly feline, but there are two or three pairs of human arms and the lowest humanoid is either giving birth or holding a skull.

The configuration of this Gobekli Tepe totem pole may symbolize ancestral connection or human evolution from infant, through adulthood and progressing to deification in animal form. Snakes are carved climbing the pole and probably symbolize transmigration of the soul since snakes shed their skins as they grow. The statue indicates the essential unity and ecological interdependence of all forms of life overriding death of the individual – an existential fact which humanity is currently rediscovering.

Stone Circles Explained by Stephen Childs is available on Amazon. A summary is also available on Youtube.

Top image: Stephen Childs theorizes that Gobekli Tepe was once a site for dramatic funerals and corpse exposure, where vultures and carnivores circled awaiting to play their part. Source: Ezume Images / Adobe Stock

By Stephen Childs

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

October 24th, 2021

October 24th, 2021  Awake Goy

Awake Goy  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: