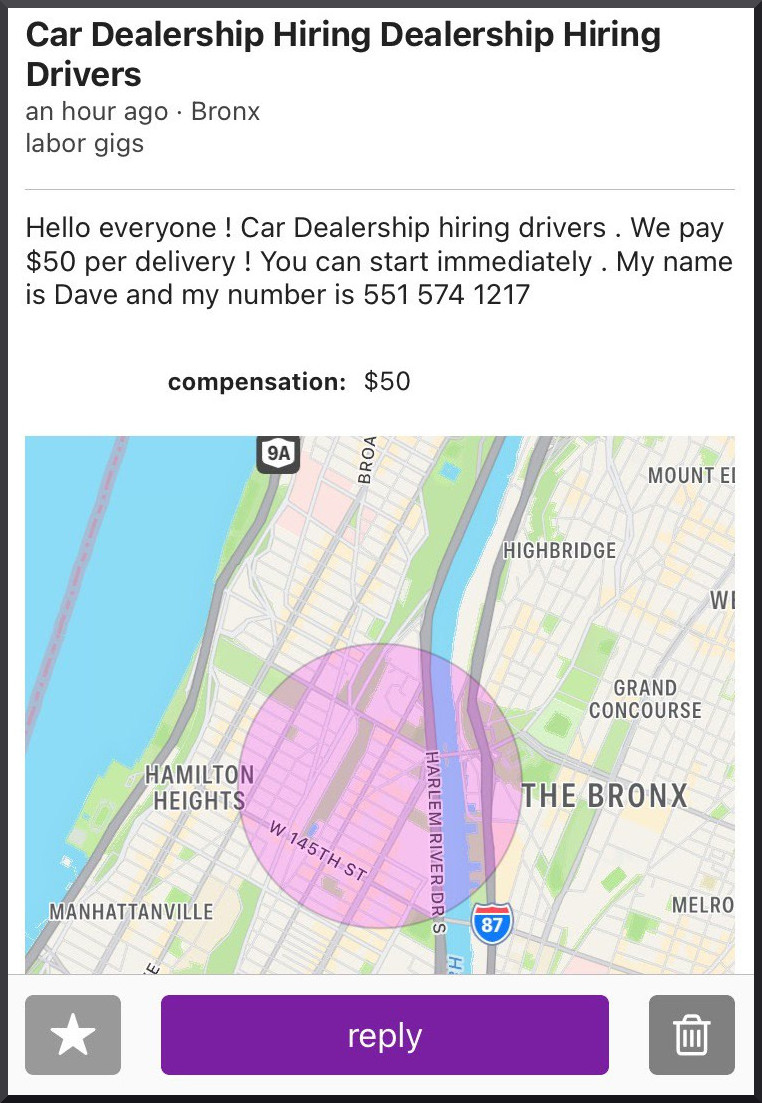

In retrospect, there were a lot of red flags. But they appeared later—not in the Craigslist ad.

“Hello everyone ! Car dealership hiring drivers,” the ad began. “We pay $50 per delivery ! You can start immediately .”

Why a car dealership would need drivers, or what it would have to deliver, wasn’t clear to Kareem Ulloa-Alvarado when he saw the ad in December. But $50 per delivery didn’t sound bad, and Kareem needed the money. So he called the number.

Within a week, Kareem was out on his electric scooter in the city, working on commission for the dealership, his backpack carrying the deliverables: thick sheets of paper with numbers printed across one side, under the words “New Jersey 30 Day Non-Resident Temporary plate.”

Temporary license plates exist so that people who buy cars can drive them before receiving metal plates. But drivers found another use for them during the pandemic: buy a temp tag on the black market and you can keep your car anonymous and off the books. No more tickets in the mail for running red lights. No CCTV footage enabling police to identify you from your license plate after you, say, shoot people in Brooklyn or run over a family in the Bronx. In recent years, New York and other parts of the country suddenly seemed to be awash in paper tags. But Kareem didn’t know any of that. Not yet at least.

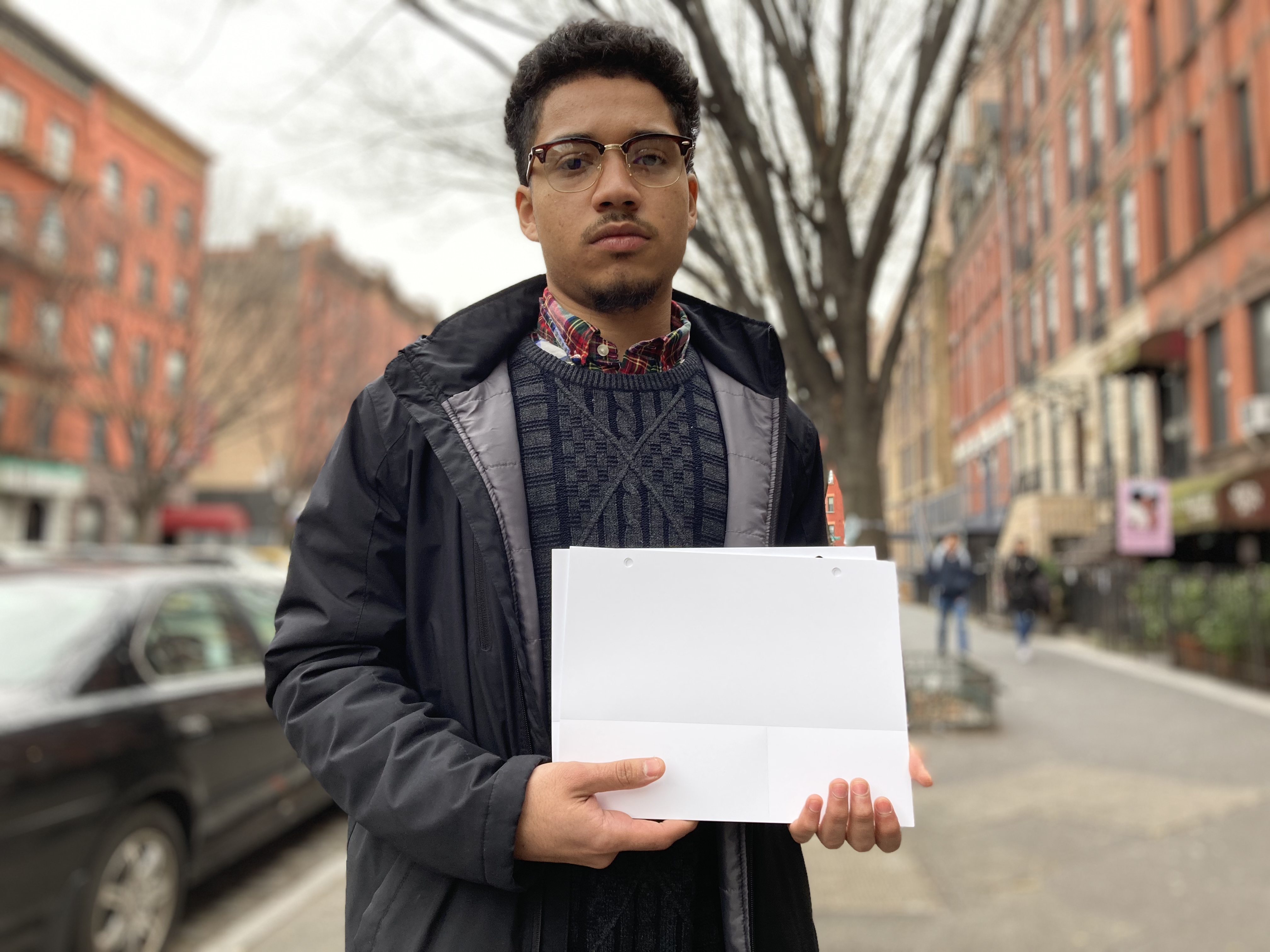

Kareem was 20 when he took the job. He was living with his parents in Harlem, making art and working odd jobs. Outgoing, with an easy smile, Kareem liked work that involved talking to people. In a way, this would prove to be a job like that.

First Kareem spoke to David, or King David, as he called himself—the guy who answered when Kareem called the number in the Craigslist ad. King David was affable. He sounded young. He didn’t provide his last name or the name of the dealership.

Kareem’s onboarding process would involve two steps, David said: buy a laser printer and meet some guy at a strip mall in Fort Lee, New Jersey. The man would give Kareem paper, David explained. New Jersey temp tags are printed on special paper that’s perforated and weatherized. If you’re printing real tags—or fake tags you want to look real—you have to use the right paper.

So, on a gloomy afternoon in December, Kareem rode his scooter over the George Washington Bridge from Harlem. Shortly after he arrived at the strip mall, a sedan rolled up, and an older, mostly bald man got out. They exchanged a few words, and the man handed Kareem the paper. He didn’t introduce himself.

The job was straightforward. Kareem received emails with temporary license plates attached as PDFs, then he printed and delivered them to customers throughout the city. Kareem’s employers instructed him to collect $150 per tag from buyers, transfer $100 to a Zelle account, and keep the balance for himself. Kareem has never owned a car, so the idea that a dealership would deliver license plates seemed reasonable enough. The customers were grateful.

“These were like normal people that owned houses and owned apartments,” Kareem said later. “I would give temporary plates to construction guys and mothers. It just seemed so legit.”

Deliveries were assigned in a Telegram group chat by dispatchers: Abo, sens3iii, TEAM KRAB, MK_Flash1. They never shared their real names. There were other couriers in the chat, too—a list shared in the chat suggests they numbered in the dozens. A dispatcher would message out an address, and the first courier to respond got the assignment.

(Motherboard reviewed the chat logs as well as screenshots of the Zelle payments, emails Kareem received from dispatchers, and the temp tag PDFs. Motherboard also spoke to a friend of Kareem’s whom Kareem told about the delivery job at the time.)

Kareem was upbeat and polite in the chat, coming across like any young, new employee eager to make a good impression.

“Good Morning Team! Looking forward to a positive, safe, and productive day,” he wrote in December, adding heart and thumbs-up emojis.

The discussion was even cheerier in Kareem’s sidebar chat with the dispatcher TEAM KRAB, who told him their name was Sophia. Sophia and Kareem’s conversation often strayed from delivery logistics, with Sophia discussing the “purification” power of snowflakes and praising Kareem’s “Beautiful spirit.”

Everything was great. Kareem would put this job on his resume, he thought. It didn’t occur to him that there was anything strange about the business, like that he was paid in cash and didn’t know the names of his employers. He’d worked plenty of short-term gigs under similar circumstances in the past—putting up posters, handing out fliers, working security at events. As far as jobs like that went, this was a pretty good one: flexible, reliable, easy. Until January 7.

Kareem set out that day to make a delivery in the Bronx. While he was talking to the would-be customer on the street, he said, two men approached from behind and one punched Kareem in the head, knocking him to the ground. Suddenly, a knife was at his throat. The men took his phone, wallet, and binder full of art, then dashed off. The customer rolled away on Kareem’s scooter.

Kareem was terrified, and his lip was bleeding. He ran to a nearby business and asked someone there to call the cops, who arrived and took Kareem to a precinct house. Kareem wanted to file a report. But after he told the detective interviewing him what he’d been doing when robbed—selling a temporary license plate—the detective smirked.

You know that’s illegal, right? Kareem remembers the detective saying. If you file a report, I can have you arrested.

Kareem was shocked. He left the station house without filing a report, his lip swelling up. Fear, shame, and indignation tumbled inside of him. From that tumult, a question emerged: Who had he been working for?

Not long before Kareem saw the ad on Craigslist, Nazareth Shahinian was attempting to sell a cookie jar on Facebook.

“1977 Queen Elizabeth Cookie jar Stamped great condition,” he posted on his page.

It was just the latest business venture for Shahinian, a prolific entrepreneur who lives in Fort Lee, New Jersey.

Shahinian’s resume is long and varied, according to his social media accounts and classified ads. It includes renting and selling property in New Jersey, installing gazebos in Canada, notarizing documents, assisting senior citizens, and, as he once wrote on Facebook: “importexport medical equipmets, medicine, pills, Doctors surgical necessary proceedures, patients transportation, Doctors travel.”

Shahinian and his sons—David and Abraham—are listed in New Jersey business records as the officers or agents of numerous companies, some whose purpose is unclear. One, called Armeniking Corporation, has little online footprint beyond a YouTube account with one video, in which Nazareth offers tips on grilling meat.

“Hi guys, how are you doing, welcome to shish kabob party,” Nazareth says, standing before a row of steaming skewers, a Panama hat covering his bald head.

Not all of the Shahinians’ business ventures have panned out. Legal records show creditors have won around a dozen judgments totaling more than $100,000 against Nazareth, his sons, and their businesses. In 2004, Nazareth was barred from taking the New Jersey real estate license exam for two years after he was caught breaking test rules by copying questions and taking notes during an exam. (Nazareth lacked “the requisite good character, honesty, integrity and trustworthiness all candidates for licensure must possess,” the state’s Real Estate Commission found.) Five years later, he pleaded guilty to unauthorized practice of law. Two years after that, he received a Masters of Law from Thomas Jefferson School of Law (which then lost its national accreditation in 2019).

The Shahinians are also in the used car industry. Business and legal records show David Shahinian and Jessie Granito, who previously listed David as her husband on Facebook, own a dealership called Gift Cars in Hasbrouck Heights. Nazareth and Abraham were previously listed as managers on Gift Cars’ Better Business Bureau webpage.

Gift Cars’ location is an odd place for a car dealership, on a dead-end industrial street wedged between New Jersey Transit tracks and Teterboro Airport. The building is strange, too: A two-story brick structure surrounded by cracked, weedy pavement that has signs outside listing dozens of other tenants, all apparently used car dealers. On a recent morning during business hours, the building seemed to be empty and Gift Cars’ office was locked.

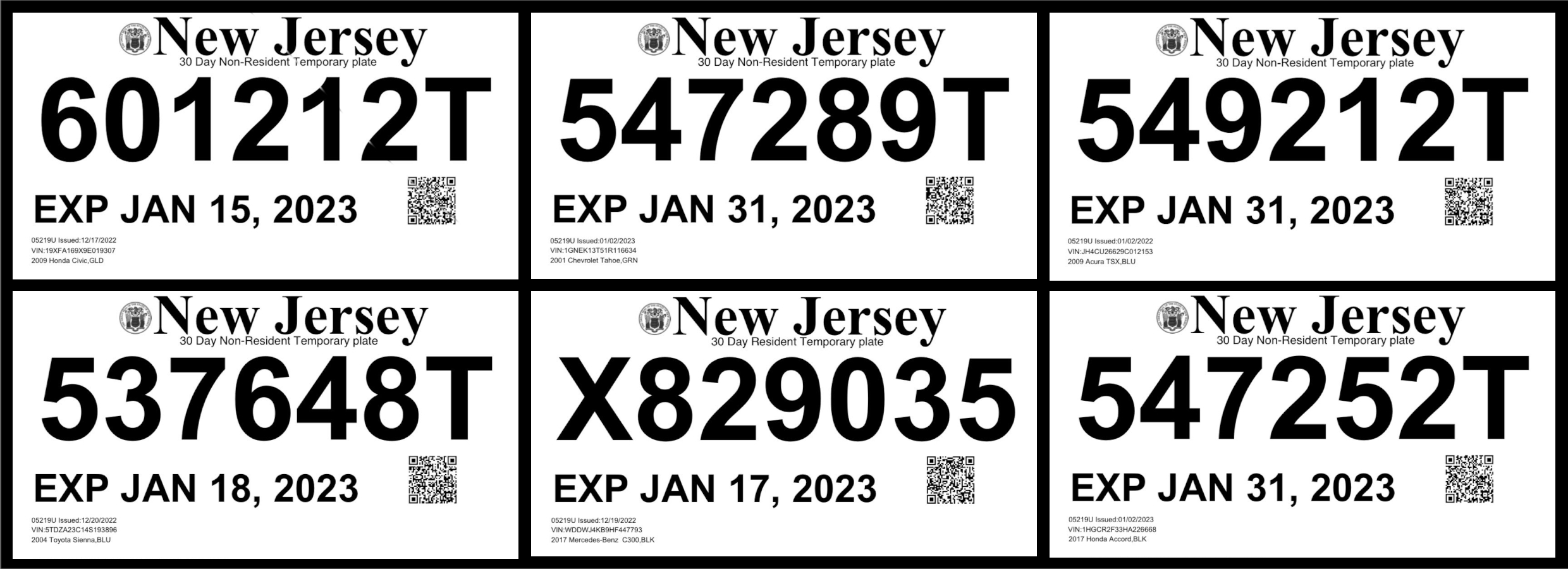

Gift Cars does not appear to be a high-volume dealership. The company does not have a website. Its Facebook page has listed just 16 cars for sale in the past seven years and includes unrelated content, like a post from 2017 that reads “Yoga Aerobics Music Dancing burning fat.” But, in 2020, something miraculous happened: The number of temp tags issued by Gift Cars increased tenfold, from under 200 in 2019 to more than 2,000 the next year, according to New Jersey Motor Vehicle Commission data obtained through records requests.

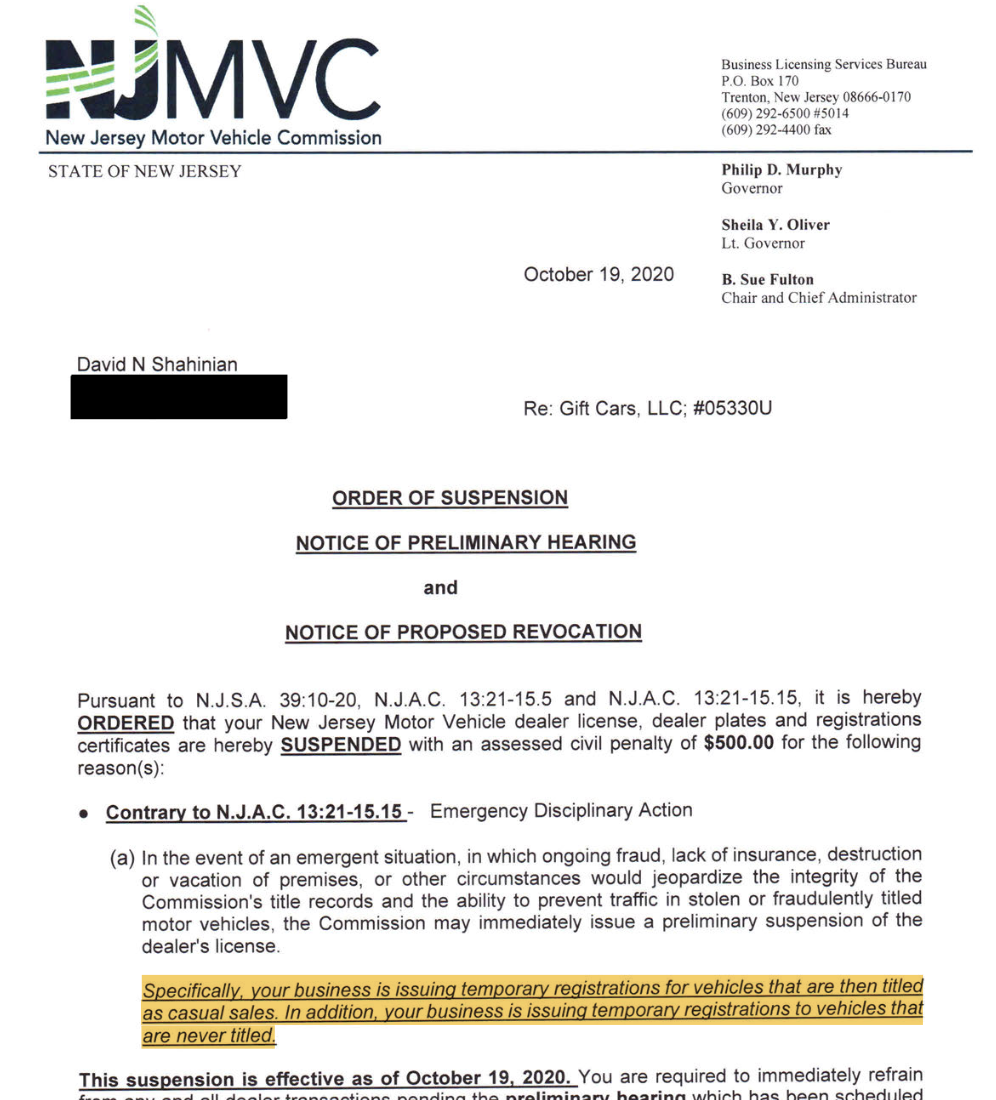

That leap in car sales was not what it seemed. The commission caught the Shahinians fraudulently issuing temps, according to an October 2020 letter from the commission obtained through a records request. And Nazareth, in an interview with Motherboard in December, admitted Gift Cars had been selling tags illegally. (It’s illegal for a dealership to issue a temp tag to someone without selling or leasing them a car.)

Nazareth told Motherboard “We didn’t know” it was illegal to sell temp tags. He characterized selling tags during the pandemic as a public service of sorts: DMVs were frequently closed at that time, making it hard to register new cars. But people still needed to get around. They needed license plates.

“Instead of thank you, the government punish us,” Nazareth said.

Gift Cars wasn’t the only dealership dabbling in illegal temp tag sales at the time. Across New Jersey and other states, obscure dealerships started printing massive numbers of temp tags while displaying little other business activity, a Streetsblog investigation found. It was around then that dubious-looking paper tags became commonplace on cars in New York City and elsewhere.

Some drivers had legitimate reasons for using those tags—the Motor Vehicle Commission extended expired New Jersey temps by a few months in 2020, for example. Others had less defensible reasons, like people using fake or fraudulent temp tags for cover while driving without licenses or car insurance. Such motorists had no trouble finding tags for sale online. Lawmakers in New York, New Jersey, and Texas are now trying to clean up the problem.

There are both real and fake temp tags on the black market—both being sold illegally. The fake ones are made by scammers with graphics software. The real ones are sold by licensed dealers and generally fetch higher prices, since they look legal to police.

Real ones typically sell for at least $100, meaning Gift Cars’ 2,000 tags were worth at least $200,000 on the black market. Nazareth told Motherboard in December that Gift Cars sold tags for $20 or $25, which, if true, would be wildly under market value but would still make those 2,000 tags worth at least $40,000. But the commission’s punishment of Gift Cars amounted to a two-month license suspension and a $500 fine. That’s the most that the commission appears to be allowed to fine dealers for a first violation under state law. (A new bill in the New Jersey legislature would change that.)

Nazareth told Motherboad in December that Gift Cars was no longer selling tags. And yet, a web of connections appears to tie Nazareth to the operation that employed Kareem.

For one, it appears to have been Nazareth who met Kareem in the parking lot in Fort Lee and gave him the temp tag paper. Kareem didn’t know it was Nazareth at the time, but confirmed it later when Motherboard showed him photos of Shahinian.

Nazareth told Motherboard that he met a man in Fort Lee to give him temp tag paper, but said the man presented himself as a dealer, or a friend of a dealer, and that it was an “honest deal.”

Then there is the Zelle account that King David told Kareem to send payments to, which was enrolled under the name “AIDA” and used an email address that included the word “inga” and six digits. Asked whether that email address belonged to his wife, Aida Yeginova, Nazareth told Motherboard “I think yes.” The email address is also associated with Yeginova on Skype. Nazareth has referred to his wife as Inga—possibly a nickname. And the six-digit number matches Yeginova’s birthday, voter records show.

Finally, there is the phone number that Kareem called to get the job. It also appeared in Armenian– and Russian-language newspapers in Canada last year, in classified ads seeking laborers, next to the name Nazareth. And Nazareth, in an interview in May, described the number as a “business line” used by Gift Cars. Notably, that same number has also appeared in Facebook ads offering New Jersey temporary license plates for sale.

Asked once again in May whether his family was still selling temp tags, Nazareth told Motherboard, “We not doing it, I’m not doing it, and I think my son also not doing it.” He elaborated: “He’s young guy. He has many partners, friends. He has million friends. Too many friends. I cannot control that.”

Motherboard repeatedly requested comments from David, Abraham, Aida, and Jessie Granito at phone numbers and email addresses associated with their names in online databases and business and legal records, as well as through Facebook and through Nazareth. They did not respond to those requests.

Around the time that Gift Cars was caught selling temp tags in 2020, J G Auto Sale, a car dealership in North Bergen, started getting strange phone calls. The callers said they’d bought temp tags from J G online and asked about purchasing more.

J G’s owner was confused. He’s never sold a tag, he told Motherboard in an interview in May. (That appears to be true: State data show the number of temps issued by J G has remained consistent and slightly below the average New Jersey dealer since 2019, and a request for commission disciplinary records involving the dealership yielded no results.) Someone was putting his dealership name on fake temp tags and selling them illegally, it seemed. The owner, who asked not to be named, says he has complained repeatedly to law enforcement and the Motor Vehicle Commission about the problem.

Tags that Kareem delivered listed the dealership name “JG Auto Sales.” The tags appear to be fake: Neither that name nor the dealer license number on the tags are in comprehensive New Jersey dealer databases. But the name is close enough to the real “J G Auto Sale” to possibly explain the strange calls in North Bergen.

Police in Hanover, New Jersey, recently arrested a man for allegedly selling a temp tag under the dealership name “JG Auto Sales.” That man, Rayquan King of Passaic, did not respond to requests for comment.

Hanover police said they did not know whether King was working with anyone else. But they did say that King had business cards that listed the dealership “JG Auto Sales” and the name “Shahaad.”

In the Telegram group chat where Kareem got assignments, the name “Shahaad” appears at the top of a list of couriers.

Kareem is glad to have some idea who might have been behind the operation that led to his busted lip, but it doesn’t make him feel that much better. He’s still out one iPhone, one wallet, one electric scooter, and one binder full of his art. (He started a GoFundMe for the scooter.)

In messages reviewed by Motherboard, Kareem told his dispatchers about getting jumped the day it happened. They were sympathetic, but nobody offered to compensate him for his on-the-job losses. Sophia told him about the importance of releasing “blocked energy” and sent him a YouTube video called “Qigong to Purge and Tonify.”

That’s when Kareem started to get angry. He was the fall guy, he realized. These people had implicated him in a criminal operation without telling him what they were really doing or making clear the risks involved. And when those risks materialized, it was Kareem getting punched in the face, not them.

Now he’s just trying to move on. He’s taking barbering classes, and he’s thinking about getting into real estate, too. Talking about what happened has helped.

“I just wanted to tell my story because I just don’t want anyone else going through it,” he said recently. “I was just duped.”

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

June 9th, 2023

June 9th, 2023  Awake Goy

Awake Goy  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: