I was weightless. We all were. Thirty-three thousand feet up in a cloudless sky, our plane had suddenly pitched into a steep dive. I felt my body float upwards and strain against my seatbelt. Passengers around me screamed. There was a loud crash in the back — a coffeepot clattering to the floor and tumbling down the aisle. Our tray tables began rattling in unison as the 757 strained through the kind of maneuver meant more for a fighter jet. Top Gun this was not, though. Our flight that Friday, April 25th, was mostly heavy-set tourists returning to California from Hawaii. More Tommy Bahama than Tom Cruise.

Weightless and staring downhill at the thirty-some rows of passengers ahead of me, I had a rare and terrible reminder of the absurd improbability of human flight. We were hairless apes crowded into a thin metal tube hurtling through the sky at a speed and height beyond anything evolution prepared us to comprehend. The violence was over after a few seconds. United 1205 leveled out, having dropped at least 600 feet without warning.

The voice of an audibly flustered flight attendant came over the speaker. “OK. That was obviously unexpected.” An understatement. The fasten-seat-belt sign was still off. A moment later, after we’d laughed and settled back into the friendly fiction of air travel as a mundane commute, her voice returned to notify us that “the pilot took evasive action to avoid an aircraft in our flight path.” Then a few minutes later: “Aloha! United Airlines will be offering today’s DirecTV entertainment free of charge. Anyone who has already purchased in-flight entertainment will receive a reimbursement on their credit card.” In 2014, when checked luggage, snacks, and movies have all become nickel-and-dime profit centers for modern air carriers, this announcement surprised me. Something bad must have occurred. Something truly unusual and unexpected. After we landed safely in LAX, I spoke with members of the flight crew and learned what happened.

Soon after reaching our cruising altitude of 33,000 feet, the collision alert system sounded an alarm. Our plane was on an imminent path with a US Airways flight over the Pacific, I learned. In these situations, the Traffic Collision Avoidance System (TCAS) communicates between the two planes, alerts the crew, and gives instruction to either dive or climb (ensuring that one plane dives while the other climbs). On United 1205, after the alarm went off, the captain looked out the windshield, exclaimed “Holy s***, there it is!” and immediately took the plane into a sharp dive. The first officer later told me the US Airways flight was “certainly too close for comfort.”

Two details in particular are unsettling:

- Visual Confirmation — At altitude, a pilot can see a long way from the cockpit. Even so, at our speed, long distances can close incredibly quickly. Our plane was cruising at 600 mph. Two planes coming at each other at that speed will close a distance of five miles in fifteen seconds.

- The Response — Our aircraft was a 757-300, the longest narrow-body twinjet ever made. Violent maneuvers like Friday’s incident are not taken for minor events. According to an Aviation Safety Inspector with the FAA in Hawaii, the severity of the response in United 1205 speaks to the severity of the threat perceived by the pilot.

The Tenerife Airport Disaster is the deadliest aviation accident in history. In 1977, on the Spanish island of Tenerife, two 747s collided on the runway. The death toll was 583.

On United 1205, I was one of 289 passengers. With the five or six crew members, the total count for our flight was around 295. We were six miles over the middle of the Pacific, so it’s safe to assume two things: 1) The US Airways flight coming at us was a passenger jet of similar size and 2) Everyone on both flights would have died. Had there been a collision, it would have been the new record, with an estimated 590 deaths, one of them mine.

The Timeline

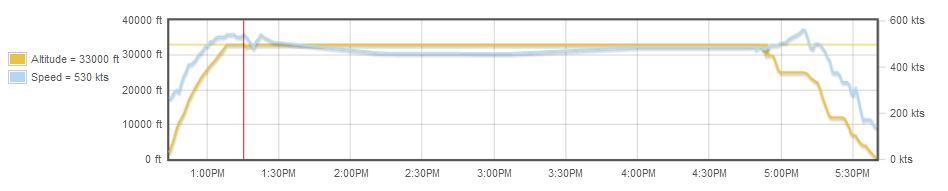

On April 25th, our flight left Kona a little after our scheduled 12:35pm takeoff. Normally, the above graph of FlightAware data would be a flat line of cruising altitude 33,000 between takeoff and landing. But the data shows a small but unmistakable anomaly around 1:15pm: our speed and altitude quickly drop and recover.

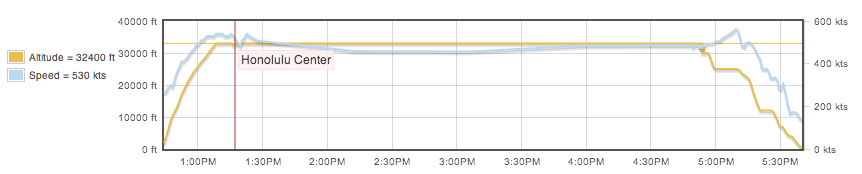

This second version of the same graph shows the lowest altitude reached (the data on the left corresponds to the moveable red line on the graph). The lowest altitude in the data is 32,400 feet — making our dive at least 600 feet. Given the poor granularity of the data here, the drop may well exceed that number.

I’ve spoken to both airlines and FAA representatives in Hawaii and Los Angeles. United Airlines confirmed that an incident occurred and that it was significant enough to merit their own internal investigation. US Airways was unwilling to comment. US Airways 663 and 692 were in that neighborhood of the Pacific Ocean at that time, but without further information, I can’t determine the other side of the near miss.

After we landed safely in Los Angeles, thankful to survive the near miss, the passenger next to me laughed and reminded me of George Carlin’s riff on word choice in air travel. “It’s not a near miss, it’s a near hit!”

I spoke with FAA representatives at length this week and my conversations led me to a shocking conclusion: airlines are essentially self-policed.

With all its barefoot body scans in the TSA line, air travel doesn’t seem to suffer from a lack of oversight. And that’s true. We devote tremendous resources to ensuring security in air travel. However, the more I learn about the industry, the more it becomes clear that our safety in the air does not have the system of oversight we might imagine.

Two airliners colliding six miles over the ocean would be a disaster of such proportion to be unthinkable to us. It was similarly unthinkable only two months ago though, that a passenger jet could simply disappear. Malaysian Airlines Flight 370 ended that fiction. It showed us that, even on a commercial flight with hundreds of other passengers, there is no global blanket of tracking enveloping us and keeping us safe.

The FAA might learn about the April 25th near miss in one of two ways: direct reporting by air-traffic controllers and indirect reporting (through the Aviation Safety Reporting System administered by NASA) by members of the flight crew. An hour east of Hawaii, “there’s no one out there but the pilot — that’s the only one seeing it” according to an FAA investigator in Hawaii. And so, when reporting the incident, the pilot decides if he wants to report the event. If reported, different points in the chain can determine it a “significant” or “non-significant” incident. The event on April 25th, which United Airlines itself considers a significant enough event to internally investigate, was either unreported or “non-significant” in the eyes of the FAA until this week.

On Friday, two weeks after the near miss and my initial call with the FAA, I followed up with the agency and learned that the Air Traffic Organization (ATO) was looking into the incident. According to the FAA official I spoke with, the sheer fact that they’re exploring the event implied to him that they saw it as “significant,” even though they’d never passed it on to the FAA with any formal categorization. Two weeks of daily ATO reports to the FAA had gone by without a mention of this likely “significant” event. This official took issue with ATO not sharing the event, but admitted that there is no requirement for sharing, only common practice.

I was shocked at the number of links in the reporting chain; not to mention how weak each appeared to be. The FAA even admitted that my initial information, the random phone call from a passenger, was “essential to [their] fact-finding.” Without the basic information I provided to them, they would not, by their own admission, have been able to connect the dots when the ATO began asking questions.

Thankful as I am that someone is examining what happened, the system appears broken. The FAA is the only regulatory body with the authority to turn lessons of a near catastrophe into improvements in policy, procedure, or training. Yet, the FAA is in the dark on a near miss that could have taken more lives than any air accident in history. Air travel has a tremendous modern safety record. My experience asking questions about United 1205 however, has painted the picture of a safety system resting on its laurels.

Human flight is a technological marvel. Flying aircraft twice the size of blue whales across whole continents is another marvel upon that. Doing so countless times in precise choreography every day is a feat upon that still. Modern air travel is such a raw miracle of technology it would almost certainly be the first of our achievements to awe generations before us.

That technology can become a crutch though. In November, the FAA released a report detailing that over-reliance on autopilot and other flight technologies has led to accidents and safety incidents:

“Pilots sometimes over-rely on automated systems — in effect, delegating authority to those systems, which sometimes resulted in deviating from the desired flight path under automated system control.” — FAA Report, “Operational Use of Flight Path Management Systems”

These ‘automation addiction’ concerns, voiced by industry and regulators alike, grew after the National Transportation Safety Board named it a potential cause of the fatal July crash of Asiana Flight 214. December’s NTSB hearings found “speed the most critical factor” leading to the disaster, and misuse of automated systems the most critical factor in the speed. The 777 approached SFO’s runway at 118 mph, far below the required minimum of 158 mph, because the pilot mistakenly believed airspeed was under automatic throttle control. The plane fell short of the runway and clipped the seawall, leading to 3 deaths and 181 injured.

Even as the FAA decries pilots’ over-reliance on the technology of their aircraft, they themselves over-rely on the technology of their safety systems. While seeking out answers for the April 25th incident, I was told by the FAA:

“Modern technology equips the airplanes with all these devices. It all worked properly, and because everything worked properly, [any investigation]’s probably not going to go a whole lot farther.” — Hawaii FAA Inspector

The achievement of modern air travel, that precise choreography, instills a hubris in those tasked with managing it. The system and its safety record are so impressive that catastrophes that almost happen apparently aren’t worth scrutiny. Instead, the FAA inspector told me that any changes would likely take place internally at the two airlines. The agency seems to rely on these companies, the creators of these infallible technologies, to self-police much in the same way that financial regulators relied on banks to self-police when it came to complicated products like mortgage-backed securities.

Imagine you’re driving on the highway at night. Suddenly, another car driving the opposite direction appears in your lane. You swerve into another lane just as the car passes. The FAA’s view would hold that nothing was amiss because your headlights revealed the oncoming car.

Clearly, in the car example and its April 25th plane equivalent, something went wrong. Someone was in the wrong place. On the ground, cars separate horizontally by always driving on the right side of the road. In the air, planes separate vertically: all eastbound flights cruise at odd altitudes (33,000 feet, 41,000 feet, etc.) while all westbound flights cruise at even altitudes (38,000 feet, 52,000 feet, etc.). Of course, plane travel has one dimension more than car travel, so its exponentially more complex. Planes take off and land, passing through odd and even altitudes in the process. They avoid weather. And their flight paths have 360 degrees of horizontal directions. Two planes flying into Paris, one from London and the other from Barcelona, aim nearly head on at each other but both qualify as “westbound” flights.

On April 25th, my United 1205 flight was on an eastbound heading from Kona to Los Angeles and had reached a cruising altitude of 33,000 feet. An odd-numbered altitude, so by the east-west/odd-even rule of thumb, we were on the right side of the highway. The US Airways flight coming at us was on the wrong side of the highway. Thankfully, my pilot saw the plane in our ‘headlights’ in time and swerved into a dive, but the lack of a disaster doesn’t mean a grave, teachable error did not occur somewhere in the process.

Near misses are terrifyingly common in high traffic areas near airports and major cities. According to an investigation by two Seattle news groups into the ASRS data, “on average more than 150 close calls are happening every day.” Nonetheless, the vast majority of these close calls involve small aircraft at low altitudes, incidents on the ground at airports, or isolated issues involving a single plane. Commercial airplanes, at cruising altitude and far from high traffic areas, rarely come close to each other. The FAA confirmed as much, telling me that my incident of two commercial jets at cruising altitude passing close enough to each other to trigger an RA in the collision avoidance system is “very rare.”

The car equivalent might be the distinction between driving in a parking lot and driving in a highway. Circling a parking lot, drivers often end up in the wrong place and cause a fender bender. Getting onto an off-ramp and heading west on an eastbound lane of a highway is a different story entirely. And one that likely doesn’t end well.

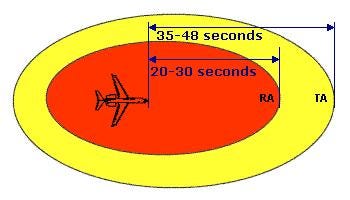

The system that ensures safe air travel, and that led my pilot to dive our plane on April 25th, is called the Traffic Collision Avoidance System (TCAS). Planes send out radio signals that create electronic “bubbles” around themselves. If two bubbles overlap, the system alerts the two pilots. The ‘Traffic Advisory’ (TA) Region gives the pilot information, but doesn’t require any action. If two planes enter each others’ ‘Resolution Advisory’ (RA) Region, the system flashes an alert and instructs each pilot to climb or dive their plane immediately. Following an RA is fundamental to safe air travel. In 2002, over southern Germany, two planes received RAs but one pilot followed the TCAS instruction to dive while the other ignored the TCAS climb order and followed air traffic controllers. Both planes descended, leading to a collision that killed everyone on board both known today as the Überlingen Disaster.

On my April 25th flight, the United pilot followed the RA he received and even had a visual of the oncoming US Airways flight. Considering the size of RA bubbles, we may have been only seconds from a collision.

Air travel is indeed extraordinarily safe. Before the July Asiana crash, the last commercial airline fatality in the United States occurred in 2009 with theColgan Air Flight 3407. Considering the number of air miles traveled in the country every year, plane travel has “nearly zero accidents per million flying miles.” Car crashes, minor and major, occur hundreds of times a day.

Regardless, plane crashes hold a unique place in our fears: the fiery violence, the lack of control — they have a scale and spectacle that makes them loom larger than their actual threat. Similarly, more Americans are killed by vending machines than sharks every year, but more people fear sharks than vending machines. Perhaps most importantly, car crashes occur with a sliding scale: fender bender to freeway pileup. Plane accidents are more binary: either nothing goes wrong or everything goes wrong.

Economists call these the ‘statistical life’ and the ‘actual life.’ Whenever a speed limit is increased, more people are likely to die — to the public, these deaths are ‘statistical lives,’ without names or stories. When comparing car crashes and plane crashes, we’re often considering the nameless numbers of car accidents to the stories and details of a single plane crash.

As a result, each plane crash seems to lead to new regulation or new training. Safety in air travel, much like security, is reactive to events. The shoebomber means we now have to remove our shoes. A single threat in England means we now have to surrender our liquids. A collision of two planes over Germany means pilots now have to follow TCAS over air traffic control.

Reactive policy is not defensive though; it prepares only for the dangers that have already come to pass. To be more robust, the agencies that manage air travel have to do two things: First, they need to collect more and better data. With the hubris of flying’s relative safety, they see their data as a flat line of perfect safety with only a few blips of outlier catastrophes.

“Currently, the commercial aviation system is the safest transportation system in the world, and the accident rate is the lowest it has ever been. This impressive record is due to many factors, including improvements in aircraft systems (such as those mentioned above), pilot training, professional pilot skills, flightcrew and air traffic procedures, improved safety data collection and analysis, and other efforts by industry and government. However, incident and accident reports suggest that flightcrews sometimes have difficulties using flight path management systems.” — FAA Report, “Operational Use of Flight Path Management Systems” (emphasis added)

If they make policies for the outliers though, they need to better collect the data between zero and one: the near misses, the errors that narrowly avoided their consequences.

Secondly, they need to communicate that data more openly and readily. To push the comparison between air safety and air security further, America’s security apparatus had intelligence on the September 11th terrorist attacks, but the knowledge was spread across different agencies and too siloed away for the dots to be connected. In the aftermath of the attacks, information sharing was identified as a key improvement in our security system.

Safety threats grow in the shadows just like security threats. Sharing information across groups means more lights shining into those shadows and more opportunities to identify a threat. The only downside to granting more people access to information is more people may leak that information, as the security apparatus saw with Manning and Snowden. Safety threats are unseen gaps in process or training though, not terrorist groups that might be able to make use of leaked information. Airlines are the only party that might object to information sharing, as their bottom lines suffer if consumers see air travel as more dangerous.

Accidents don’t occur because everything went wrong; they occur because just enough went wrong. Thankfully, air travel has become more safe with time, but that doesn’t mean its technology is perfect. Had just one more thing gone wrong two weeks ago, two jetliners would have collided in the largest airline disaster in history.

As mentioned, the crash currently with the most fatalities is the Tenerife Airport Disaster, in which two 747s collided on a Canary Island runway in 1977. For that tragedy to occur, even nearly forty years ago when the safety system was much less advanced, a string of unlikely events had to occur:

- A bomb explosion at the Gran Canaria International Airport forced planes to divert to the smaller airport on nearby Tenerife.

- Dense fog eliminated visibility for air traffic controllers and pilots. Tenerife’s small airport had no radar, and so without visibility, voice communication was the only way to locate the planes.

- The pilot of the KLM 747 did not have takeoff clearance when he attempted to lift off and collided with the taxiing PanAm 747.

- Tower communication with the two planes led to a radio interference in the KLM cockpit that prevented the captain’s misinterpretation of takeoff clearance from being corrected.

The United flight two weeks ago had at least one thing go wrong. Two jetliners six miles over the Pacific don’t come within scraping distance of each other without something going amiss. Thankfully, just enough went right that a disaster even beyond the scale of Tenerife was averted.

Source Article from http://www.lewrockwell.com/2014/05/no_author/2-weeks-ago-i-almost-died/

Views: 0

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

May 24th, 2014

May 24th, 2014  Peter Nolan

Peter Nolan  Posted in

Posted in