Above photo: CEO of Twitter Jack Dorsey (R) and Facebook COO Sheryl Sandberg (L) are sworn in to testify before the Senate Intelligence Committee on Capitol Hill in Washington, DC, on September 5, 2018. Jim Watson / AFP via Getty Images.

Threaten the First Amendment.

In their zeal for control over online speech, House Democrats are getting closer and closer to the constitutional line, if they have not already crossed it.

For the third time in less than five months, the U.S. Congress has summoned the CEOs of social media companies to appear before them, with the explicit intent to pressure and coerce them to censor more content from their platforms. On March 25, the House Energy and Commerce Committee will interrogate Twitter’s Jack Dorsey, Facebooks’s Mark Zuckerberg and Google’s Sundar Pichai at a hearing which the Committee announced will focus “on misinformation and disinformation plaguing online platforms.”

The Committee’s Chair, Rep. Frank Pallone, Jr. (D-NJ), and the two Chairs of the Subcommittees holding the hearings, Mike Doyle (D-PA) and Jan Schakowsky (D-IL), said in a joint statement that the impetus was “falsehoods about the COVID-19 vaccine” and “debunked claims of election fraud.” They argued that “these online platforms have allowed misinformation to spread, intensifying national crises with real-life, grim consequences for public health and safety,” adding: “This hearing will continue the Committee’s work of holding online platforms accountable for the growing rise of misinformation and disinformation.”

House Democrats have made no secret of their ultimate goal with this hearing: to exert control over the content on these online platforms. “Industry self-regulation has failed,” they said, and therefore “we must begin the work of changing incentives driving social media companies to allow and even promote misinformation and disinformation.” In other words, they intend to use state power to influence and coerce these companies to change which content they do and do not allow to be published.

I’ve written and spoken at length over the past several years about the dangers of vesting the power in the state, or in tech monopolies, to determine what is true and false, or what constitutes permissible opinion and what does not. I will not repeat those points here.

Instead, the key point raised by these last threats from House Democrats is an often-overlooked one: while the First Amendment does not apply to voluntary choices made by a private company about what speech to allow or prohibit, it does bar the U.S. Government from coercing or threatening such companies to censor. In other words, Congress violates the First Amendment when it attempts to require private companies to impose viewpoint-based speech restrictions which the government itself would be constitutionally barred from imposing.

It may not be easy to draw where the precise line is — to know exactly when Congress has crossed from merely expressing concerns into unconstitutional regulation of speech through its influence over private companies — but there is no question that the First Amendment does not permit indirect censorship through regulatory and legal threats.

Ben Wizner, Director of the ACLU’s Speech, Privacy, and Technology Project, told me that while a constitutional analysis depends on a variety of factors including the types of threats issued and how much coercion is amassed, it is well-established that the First Amendment governs attempts by Congress to pressure private companies to censor:

For the same reasons that the Constitution prohibits the government from dictating what information we can see and read (outside narrow limits), it also prohibits the government from using its immense authority to coerce private actors into censoring on its behalf.

In a January Wall Street Journal op-ed, tech entrepreneur Vivek Ramaswamy and Yale Law School’s constitutional scholar Jed Rubenfeld warned that Congress is rapidly approaching this constitutional boundary if it has not already transgressed it. “Using a combination of statutory inducements and regulatory threats,” the duo wrote, “Congress has co-opted Silicon Valley to do through the back door what government cannot directly accomplish under the Constitution.”

That article compiled just a small sample of case law making clear that efforts to coerce private actors to censor speech implicate core First Amendment free speech guarantees. In Norwood v. Harrison (1973), for instance, the Court declared it “axiomatic” — a basic legal principle — that Congress “may not induce, encourage or promote private persons to accomplish what it is constitutionally forbidden to accomplish.” They noted: “For more than half a century courts have held that governmental threats can turn private conduct into state action.”

In 2018, the ACLU successfully defended the National Rifle Association (NRA) in suing Gov. Andrew Cuomo and New York State on the ground that attempts of state officials to coerce private companies to cease doing business with the NRA using implicit threats — driven by Cuomo’s contempt for the NRA’s political views — amounted to a violation of the First Amendment. Because, argued the ACLU, the communications of Cuomo’s aides to banks and insurance firms “could reasonably be interpreted as a threat of retaliatory enforcement against firms that do not sever ties with gun promotion groups,” that conduct ran afoul of the well-established principle “that the government may violate the First Amendment through ‘action that falls short of a direct prohibition against speech,’ including by retaliation or threats of retaliation against speakers.” In sum, argued the civil liberties group in reasoning accepted by the court:

Courts have never required plaintiffs to demonstrate that the government directly attempted to suppress their protected expression in order to establish First Amendment retaliation, and they have often upheld First Amendment retaliation claims involving adverse economic action designed to chill speech indirectly.

In explaining its rationale for defending the NRA, the ACLU described how easily these same state powers could be abused by a Republican governor against liberal activist groups — for instance, by threatening banks to cease providing services to Planned Parenthood or LGBT advocacy groups. When the judge rejected Cuomo’s motion to dismiss the NRA’s lawsuit, Reuters explained the key lesson in its headline:

Perhaps the ruling most relevant to current controversies occurred in the 1963 Supreme Court case Bantam Books v. Sullivan. In the name of combatting the “obscene, indecent and impure,” the Rhode Island legislature instituted a commission to notify bookstores when they determined a book or magazine to be “objectionable,” and requested their “cooperation” by removing it and refusing to sell it any longer. Four book publishers and distributors sued, seeking a declaration that this practice was a violation of the First Amendment even though they were never technically forced to censor. Instead, they ceased selling the flagged books “voluntarily” due to fear of the threats implicit in the “advisory” notices received from the state.

In a statement that House Democrats and their defenders would certainly invoke to justify what they are doing with Silicon Valley, Rhode Island officials insisted that they were not unconstitutionally censoring because their scheme “does not regulate or suppress obscenity, but simply exhorts booksellers and advises them of their legal rights.”

In rejecting that disingenuous claim, the Supreme Court conceded that “it is true that [plaintiffs’] books have not been seized or banned by the State, and that no one has been prosecuted for their possession or sale.” Nonetheless, the Court emphasized that Rhode Island’s legislature — just like these House Democrats summoning tech executives — had been explicitly clear that their goal was the suppression of speech they disliked: “the Commission deliberately set about to achieve the suppression of publications deemed ‘objectionable,’ and succeeded in its aim.” And the Court emphasized that the barely disguised goal of the state was to intimidate these private book publishers and distributors into censoring by issuing implicit threats of punishment for non-compliance:

It is true, as noted by the Supreme Court of Rhode Island, that [the book distributor] was “free” to ignore the Commission’s notices, in the sense that his refusal to “cooperate” would have violated no law. But it was found as a fact — and the finding, being amply supported by the record, binds us — that [the book distributor’s] compliance with the Commission’s directives was not voluntary. People do not lightly disregard public officers’ thinly veiled threats to institute criminal proceedings against them if they do not come around, and [the distributor’s] reaction, according to uncontroverted testimony, was no exception to this general rule. The Commission’s notices, phrased virtually as orders, reasonably understood to be such by the distributor, invariably followed up by police visitations, in fact stopped the circulation of the listed publications ex proprio vigore [by its own force]. It would be naive to credit the State’s assertion that these blacklists are in the nature of mere legal advice when they plainly serve as instruments of regulation.

In sum, concluded the Bantam Books Court: “their operation was in fact a scheme of state censorship effectuated by extra-legal sanctions; they acted as an agency not to advise but to suppress.”

Little effort is required to see that Democrats, now in control of the Congress and the White House, are engaged in a scheme of speech control virtually indistinguishable from those long held unconstitutional by decades of First Amendment jurisprudence. That Democrats are seeking to use their control of state power to coerce and intimidate private tech companies to censor — and indeed have already succeeded in doing so — is hardly subject to reasonable debate. They are saying explicitly that this is what they are doing.

Because “big tech has failed to acknowledge the role they’ve played in fomenting and elevating blatantly false information to its online audiences,” said the Committee Chairs again summoning the social media companies, “we must begin the work of changing incentives driving social media companies to allow and even promote misinformation and disinformation.”

The Washington Post, in reporting on this latest hearing, said the Committee intends to “take fresh aim at the tech giants for failing to crack down on dangerous political falsehoods and disinformation about the coronavirus.” And lurking behind these calls for more speech policing are pending processes that could result in serious punishment for these companies, including possible antitrust actions and the rescission of Section 230 immunity from liability.

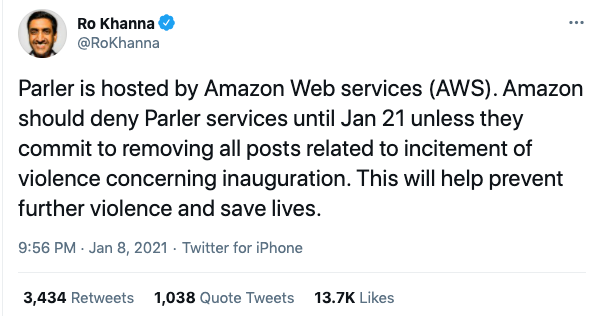

This dynamic has become so common that Democrats now openly pressure Silicon Valley companies to censor content they dislike. In the immediate aftermath of the January 6 Capitol riot, when it was falsely claimed that Parler was the key online venue for the riot’s planning — Facebook, Google’s YouTube and Facebook’s Instagram were all more significant — two of the most prominent Democratic House members, Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-NY) and Rep. Ro Khanna (D-CA), used their large social media platforms to insist that Silicon Valley monopolies remove Parler from their app stores and hosting services:

Within twenty-four hours, all three Silicon Valley companies complied with these “requests,” and took the extraordinary step of effectively removing Parler — at the time the most-downloaded app on the Apple Store — from the internet. We will likely never know what precise role those tweets and other pressure from liberal politicians and journalists played in their decisions, but what is clear is that Democrats are more than willing to use their power and platforms to issue instructions to Silicon Valley about what they should and should not permit to be heard.

Leading liberal activists and some powerful Democratic politicians, such as then-presidential-candidate Kamala Harris, had long demanded former President Donald Trump’s removal from social media. After the Democrats won the White House — indeed, the day after Democrats secured control of both houses of Congress with two wins in the Georgia Senate run-offs — Twitter, Facebook and other online platforms banned Trump, citing the Capitol riot as the pretext.

While Democrats cheered, numerous leaders around the world, including many with no affection for Trump, warned of how dangerous this move was. Long-time close aide of the Clintons, Jennifer Palmieri, posted a viral tweet candidly acknowledging — and clearly celebrating — why this censorship occurred. With Democrats now in control of the Congressional committees and Executive Branch agencies that regulate Silicon Valley, these companies concluded it was in their best interest to censor the internet in accordance with the commands and wishes of the party that now wields power in Washington:

It has not escaped my attention that the day social media companies decided there actually IS more they could do to police Trump’s destructive behavior was the same day they learned Democrats would chair all the congressional committees that oversee them.

— Jennifer Palmieri (@jmpalmieri) January 7, 2021

The last time CEOs of social media platforms were summoned to testify before Congress, Sen. Ed Markey (D-MA) explicitly told them that what Democrats want is more censorship — more removal of content which they believe constitutes “disinformation” and “hate speech.” He did not even bother to hide his demands: “The issue is not that the companies before us today are taking too many posts down; the issue is that they are leaving too many dangerous posts up”:

When it comes to censorship of politically adverse content, sometimes explicit censorship demands are unnecessary. Where a climate of censorship prevails, companies anticipate what those in power want them to do by anticipatorily self-censoring to avoid official retaliation. Speech is chilled without direct censorship orders being required.

That is clearly what happened after Democrats spent four years petulantly insisting that they lost the 2016 election not because they chose a deeply disliked nominee or because their neoliberal ideology wrought so much misery and destruction, but instead, they said, because Facebook and Twitter allowed the unfettered circulation of incriminating documents hacked by Russia. Anticipating that Democrats were highly likely to win in 2020, the two tech companies decided in the weeks before the election — in what I regard as the single most menacing act of censorship of the last decade — to suppress or outright ban reporting by The New York Post on documents from Hunter Biden’s laptop that raised serious questions about the ethics of the Democratic front-runner for president. That is a classic case of self-censorship to please state officials who wield power over you.

All of this raises the vital question of where power really resides when it comes to controlling online speech. In January, the far-right commentator Curtis Yarvin, whose analysis is highly influential among a certain sector of Silicon Valley, wrote a provocative essay under the headline “Big tech has no power at all.” In essence, he wrote, Facebook as a platform is extremely powerful, but other institutions — particularly the corporate/oligarchical press and the government — have seized that power from Zuckerberg, and re-purposed it for their own interests, such that Facebook becomes their servant rather than the master:

However, if Zuck is subject to some kind of oligarchic power, he is in exactly the same position as his own moderators. He exercises power, but it is not his power, because it is not his will. The power does not flow from him; it flows through him. This is why we can say honestly and seriously that he has no power. It is not his, but someone else’s.

Why doth Zuck ban shitlords? Is the creator of “Facemash” passionately committed to social justice? Well, maybe. He may have no power, but he is still a bigshot. Bigshots often do get religion in later life—especially when everyone around them is getting it. But—does he have a choice? If he has no choice—he has no power.

For reasons not fully relevant here, I don’t agree entirely with that paradigm. Tech monopolies have enormous amounts of power, sometimes greater than nation-states themselves. We just saw that in Google and Facebook’s battles with the entire country of Australia. And they frequently go to war with state efforts to regulate them. But it is unquestionably true that these social media companies — which set out largely for reasons of self-interest and secondarily due to a free-internet ideology to offer a content-neutral platform — have had the censorship obligation foisted upon them by a combination of corporate media outlets and powerful politicians.

One might think of tech companies, the corporate media, the U.S. security state, and Democrats more as a union — a merger of power — rather than separate and warring factions. But whatever framework you prefer, it is clear that the power of social media companies to control the internet is in the hands of government and its corporate media allies at least as much as it is in the hands of the tech executives who nominally manage these platforms.

And it is precisely that reality that presents serious First Amendment threats. As the above-discussed Supreme Court jurisprudence demonstrates, this form of indirect and implicit state censorship is not new. Back in 2010, the war hawk Joe Lieberman abused his position as Chairman of the Senate Armed Services Committee to “suggest” that financial services and internet hosting companies such as Visa, MasterCard, Paypal, Amazon and Bank of America, should terminate their relationship with WikiLeaks on the ground that the group, which was staunchly opposed to Lieberman’s imperialism and militarism, posed a national security threat. Lieberman hinted that they may face legal liability if they continued to process payments for WikiLeaks.

Unsurprisingly, these companies quickly obeyed Lieberman’s decree, preventing the group from collecting donations. When I reported on these events for Salon, I noted:

That Joe Lieberman is abusing his position as Homeland Security Chairman to thuggishly dictate to private companies which websites they should and should not host — and, more important, what you can and cannot read on the Internet — is one of the most pernicious acts by a U.S. Senator in quite some time. Josh Marshall wrote yesterday: “When I’d heard that Amazon had agreed to host Wikileaks I was frankly surprised given all the fish a big corporation like Amazon has to fry with the federal government.” That’s true of all large corporations that own media outlets — every one — and that is one big reason why they’re so servile to U.S. Government interests and easily manipulated by those in political power. That’s precisely the dynamic Lieberman was exploiting with his menacing little phone call to Amazon (in essence: Hi, this is the Senate’s Homeland Security Committee calling; you’re going to be taking down that WikiLeaks site right away, right?). Amazon, of course, did what they were told.

(Along with Daniel Ellsberg, Laura Poitras and others, I co-founded the Freedom of the Press Foundation in part to collect donations on behalf of WikiLeaks to ensure that the government could never again shut down press groups that it disliked through such pressure campaigns and implicit threats, precisely because it was so clear that this indirect means of attacking press freedom was dangerous and unconstitutional).

What made Lieberman’s implicit threats in the name of “national security” so despotic was that they were clearly intended to punish and silence a group working against his political agenda. And that is precisely true of the motives of these House Democrats in demanding greater censorship in the name of combating “misinformation” and “hate speech”: their demands almost always, if not always, mean silencing those who are opposed to their ideology and political agenda. As but one example: one is perfectly free to opine online, as many Democrats do, that the 2000, 2004 and 2016 presidential elections (won by Republicans) were the by-products of electoral fraud, but making that same claim about the 2020 election (won by a Democrat) will result in immediate banning.

The power to control the flow of information and the boundaries of permissible speech is a hallmark of an authoritarian regime. It is a power as intoxicating as it is menacing. When it comes to the internet, our primary means of communicating with one another, that power nominally rests in the hands of private corporations in Silicon Valley.

But increasingly, the Democratic-controlled government and their allies in the corporate media are realizing that they can indirectly and through coercion seize and wield that power for themselves. The First Amendment is implicated by these coercive actions as much as if Congress enacted laws explicitly mandating censorship of their political opponents.

Related posts:

Views: 0

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

February 23rd, 2021

February 23rd, 2021  Awake Goy

Awake Goy

Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: