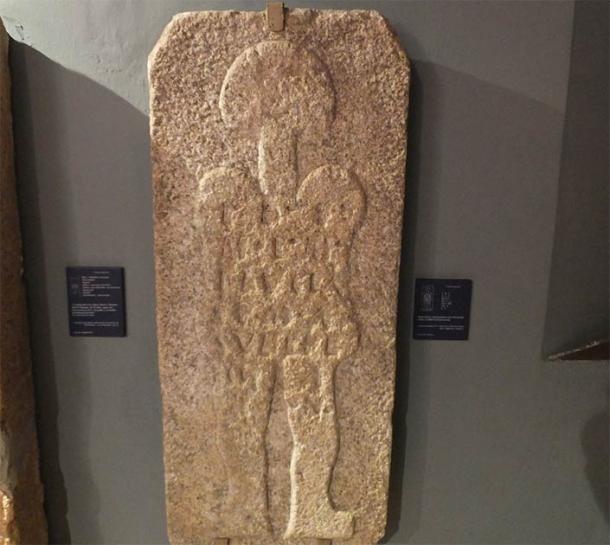

Some artifacts seem to be easy to misunderstand or are not well understood at all and this leads to wild theories. One of the biggest curiosities on display at the Caceres Museum in Caceres, Spain is a stele or upright stone slab that originally stood at the southern end of the cemetery in the nearby village of Casar. The carving on the stele appears to be a human figure with a misshapen head and bulbous shoulders. It has been dubbed by some “the astronaut of Casar”, but why?

The stele has an inscription, which is in Latin letters , but, so far, no one has managed to decipher the text. This has led to a great deal of speculation regarding the nature of this carving. Some fringe theorists have even gone as far as to suggest that it is an image of an of extra-terrestrial, hence the name “the astronaut of Casar.” But archaeological and linguistic analysis of the astronaut of Casar stele shows that the unusual features of the stele can all be explained with the knowledge that scholars have of the cultures and languages of ancient Iberia. Within this explanation, visitations from extra-terrestrials are not necessary. Nonetheless, the astronaut of Casar artifact does highlight ways that the science of archaeology may one day be able to contribute to the search for extra-terrestrial intelligence.

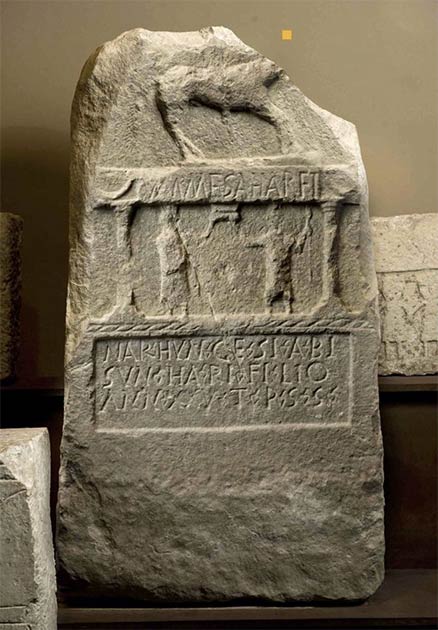

The stele dubbed “astronaut of Casar” is exhibited in the Caceres Museum, Caceres, Spain. ( verpueblos)

The Mysterious Astronaut Of Casar Stele

The astronaut of Casar stele was originally located in the cemetery of Casar, a village outside of the city of Caceres, Spain. The image appears to have generated a lot of local suspicion and superstition. It is alleged that villagers would cross themselves as they walked by the stele and that children would throw rocks at it.

The figure in the stele does look strange. His head is misshapen and appears slightly too large. His shoulders also appear to bulge out. Although the carving is weathered, the figure looks like he is smiling. The image has been suggested to be that of a Celtiberian warrior made in the 2nd or 1st century BC. The inscription in Latin letters suggests that it was written during Roman times or just before the Roman occupation of Iberia.

Most mysterious of all is the inscription on the astronaut of Casar stele. Although the inscription is in the Latin script it appears to be written in an unknown language . The language is not completely mysterious, however, since it is likely an Indo-European language. Nonetheless, scholars have not been able to translate it and some say that it cannot be translated.

The Astronaut Of Casar Stele Inscription Origin Theories

At the beginning of the Roman period in Spain, several languages were spoken on the Iberian Peninsula including Celtiberian, Lusitanian, Tartessian, proto-Basque, Latin, and probably Greek and Punic. Of these languages, Celtiberian, Lusitanian, Tartessian, and proto-Basque were native to the Iberian Peninsula while the others were introduced by foreign cultures.

The equally mysterious Stela of Hernan Perez VI, like the astronaut of Casar stele, was also found in Caceres, Spain. It is carved in a single granite block and shows etched eyes, eyebrows, nose and mouth. (manuel m. v. / CC BY 2.0 )

Although the astronaut of Casar stele inscription seems mysterious it could have been written in one of the lesser-known native Iberian languages. The understanding of many of the Iberian languages is fragmentary and only a handful of inscriptions or documents have been found for some of these languages.

This makes it probable that the inscription uses words from Iberian languages that have not been found in other inscriptions. The fact that it appears to be an Indo-European language may also help to identify the language. One way to identify the language is to examine each of the Iberian languages and determine which one is most likely the dialect used in the inscription on the stele.

The Inscription Could Be In The Basque Language

The original, ancient Basque language was already being spoken in northern Spain in Roman times. The Basque language is unique among western European languages in that it is a non-Indo-European language. Ancient Basque is a language isolate, and its language family is unknown. This has led to speculation about the origins of the Basque people, including the idea that they descend from Paleolithic hunter-gatherers , although current evidence suggests that they are more closely related to early Neolithic farmers .

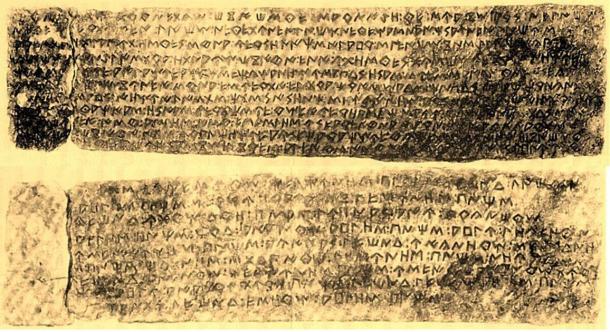

An ancient inscription written in proto-Basque. (Nafarroako Gobernua – Gobierno de Navarra / CC BY-SA 4.0 )

The Basque language is agglutinative, meaning that phrases are constructed from root words using prefixes and suffixes. The Basque language also follows the SOV (subject-object-verb) word order, in contrast to languages, such as English, that have a SVO (subject-verb-object) word order. Other languages that are SOV, like Basque, include Japanese and Turkish.

The ancient Basque language influenced the development of Castilian Spanish. Certain features of the Spanish language, such as the lack of consonant clusters, are features that come from the Basque language. Furthermore, certain Spanish words, such as arroyo and izquierda, are Basque in origin.

Although the Basque language, or at least a proto-Basque language, existed during the time the astronaut of Casar stele was made, it was largely restricted to northern Spain. However, the stele was found in southwestern Spain near the modern Portugal border. Also, the inscription appears to be Indo-European, suggesting that the language was more likely a Celtic or Romance language, the two Indo-European language groups that were most prevalent in the Iberian Peninsula at the time. All these facts suggest Basque may not be the best way to figure out the inscription on the astronaut of Casar stele.

What About Celtiberian?

Celtiberian was spoken on the Iberian Peninsula until about the 1st century BC. Celtiberian is a Celtic language that is related to the Gaelic languages of Ireland, Scotland, and the Isle of Man. This is interesting because the Irish Book of Invasions claims that the Irish descended from the Milesians who were supposed to have come from Iberia.

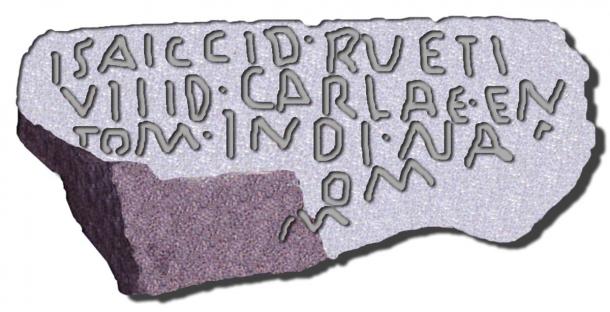

An example of the ancient Celtiberian writing script. ( Public domain )

The Celtiberians are described by Roman writers as having been a mixture of Celtic and native Iberian stock. They may have been related to the Hallstatt culture, a Celtic culture known across Europe, which first entered the Iberian Peninsula around 600 BC.

About two hundred Celtiberian inscriptions have been found. Considering the possible origin of the Celtiberians as a mixed Celtic and Iberian population, the Celtiberian language may have loanwords from early non-Indo-European Iberian languages. The Celtiberians also used their own script, which was similar to other Iberian scripts.

It is possible that the inscription on the stele is in Celtiberian, but the Celtiberian language is relatively well known and would be more likely to be recognized. Also, the Celtiberians lived to the northeast of the region in which the stele was found. This makes it less likely that the inscription was in Celtiberian.

Would Lusitanian Be A Better Candidate?

Lusitanian was a language spoken in western Iberia. It is named for the realm of the Lusitania, where inscriptions in the Lusitanian language have been found. However, few inscriptions in the Lusitanian language have been uncovered possibly suggesting that the language was not typically used for official documents or written declarations. The Lusitanian language appears to have been mainly written in the Latin script even though native scripts are found in surrounding regions.

The Lusitanian script. ( Public domain )

Lusitanian was spoken in the general vicinity of the region in which the stele was found. Also, the Lusitanian language was generally written in the Latin script used for the astronaut of Casar stele inscription. The timeframe of when the language was used, from the 1st century BC to the 2nd century AD, is also roughly consistent with the period during which scholars believe that the stele was made.

Nonetheless, Lusitanian is still a fairly well-known language so a Lusitanian inscription might be more likely to be recognized. For this reason, it is possible that the inscription is written in a yet rarer, or at least less well-known, Indo-European language.

Maybe The Tartessian Language Is The Key

The Tartessian language was spoken in southwestern Iberia in what is today southern Portugal and southwestern Spain. It is named for the city of Tartessus known for its great wealth. The region surrounding Tartessus was considered highly valuable by ancient civilizations such as the Phoenicians, the Greeks, and probably the Romans, because of its silver mines. The region of Tartessus was also distinctive in having retained a largely pre-Celtic, Iberian character, whereas the northern parts of Iberia were more influenced by Celtic culture or conquered by Celtic peoples who displaced or absorbed the native Iberian populations.

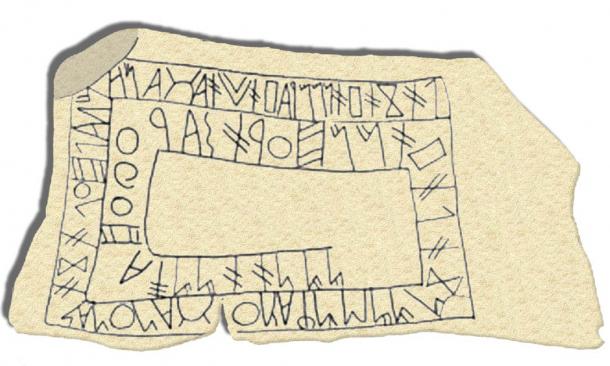

The Tartessian script. (Papix / Public domain )

The Tartessian language used its own script which has not yet been deciphered. For this reason, the Tartessian language is shrouded in mystery. It is uncertain whether Tartessian was a Celtic language or more related to pre-Celtic Iberian languages. Some scholars believe that Tartessian was related to Lusitanian and some even call it southern Lusitanian.

It is not known if Latin letters were ever used to write Tartessian or if Tartessian continued to be spoken into Roman times. The latest inscriptions in the Tartessian script only date to the 5th century BC. Nonetheless, The Tartessian language was probably spoken in the vicinity of where the stele was found, and it is a language that is largely unknown and undeciphered. For this reason, it is possible that the language of the inscription could be Tartessian.

This is speculation, but it is possible that the stele could have been made by a community living in the vicinity of modern-day Caceres which lived in Roman times but still spoke Tartessian or Lusitanian as a mother tongue. They may have forgotten how to write the script of their mother tongue, so they wrote the inscription using Latin letters.

Was The Man of Casar An Ancient Astronaut?

There has been much speculation among fringe theorists that the man depicted on the Casar stele is not a human being. This is mainly due to the unusually shaped head and bulging shoulders of the figure that make it look like he is wearing a spacesuit. The oddly shaped head bears a passing resemblance to the big-headed aliens of popular science fiction and UFO lore.

Some think the odd shape is reminiscent of a space suit. (Alberto del Barrio Herrero / CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 )

Although this is an interesting idea, all the evidence surrounding the stele can be explained by conventional means. The inscription is in an unknown language, but it is most-likely Indo-European. Also, the stele appears to be extremely weathered so the misshapen appearance of the head could be due to time and weathering. Moreover, it could be that he is wearing a helmet, or it could be his hairstyle. Also, besides the passing resemblance to modern depictions of extra-terrestrials or astronauts, there is nothing unusual or otherworldly about the man on the stele. It looks like it was carved out of stone by human tools and it fits into the archaeological and historical context of Celtiberian and Roman Spain. The only reason to believe that the figure is an extra-terrestrial is if there is a strong desire on the part of the observer for the figure to be an extra-terrestrial.

Another reason that it is unlikely that this is an extra-terrestrial is the low probability that an intelligent being from another planet would resemble a human being. The fact that it looks so human makes it likely that it is meant to depict something that is earthly in origin.

Implications For The Search For Extra-terrestrial Life

Most claims that particular archaeological discoveries reveal past visitations by life from another planet have eventually been disproven or at least found to be unconvincing. Nonetheless, this does not mean that there is no place for archaeology in the search for evidence of extra-terrestrial intelligence on planet earth.

The big question about extra-terrestrials is did they visit planet earth or didn’t they? (fergregory / Adobe Stock )

The vast majority of organisms that have evolved over the course of the earth’s history have gone extinct. It is likely that the same rule applies on other planets where life and civilization have evolved. For this reason, we will probably find an extinct extra-terrestrial civilization before we find a living one.

Therefore, it makes sense to use archaeological methods to search for extra-terrestrial intelligence. One way to conduct exo-archaeology would be to look at nearby stars for signs of megastructures, such as Dyson spheres. This would use the tools of astrophysics and would not be significantly different from traditional SETI research approaches, which focus on extra-solar and extra-terrestrial intelligence.

Another approach that could be considered exo-archaeology would be to use the remote sensing tools of planetary science to survey planetary surfaces, such as the moon and Mars. It is unlikely that anything would be found from such a survey, but the discovery that another technological civilization existed in our solar system would be extraordinary. So, a low-cost search of high-resolution images from spacecraft that have visited the Moon and Mars would seem a good start.

Finding extra-terrestrial intelligence, however, requires critical thinking and careful analysis of the evidence. Claims such as the astronaut of Casar can be easily explained without any extra-terrestrials. A true archaeological discovery of intelligent life outside of Earth would be one which was unmistakably non-earthly in origin, such as the discovery of artificial structures made of materials that did not exist anywhere else on earth or in our solar system.

Conclusion? The Astronaut Of Casar Was Human Made!

The astronaut of Casar stele is mysterious but the inscription and the appearance of the figure can both be explained without involving any theories about extra-terrestrials. Nonetheless, the astronaut of Casar does reveal the increasing enthusiasm for archaeology as a big part of the search for extra-terrestrial intelligence. Archaeology does have a role to play in this quest, but the so-called astronaut of Casar is really nothing more than an example of earthly archaeology being mistaken for something otherworldly.

Top image: The stele dubbed by some as the “astronaut of Casar” is exhibited in the Caceres Museum, Caceres, Spain. Source: Left; Alberto del Barrio Herrero / CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 , Right; verpueblos

By Caleb Strom

References

“Celtiberian.” N.D. Omniglot. Available at: https://omniglot.com/writing/celtiberian.htm

“Iberian.” 2016. Encyclopaedia Britannica. Available at: https://www.britannica.com/topic/Iberian.

“Iberian scripts.” N.D. Omniglot. Available at:

https://omniglot.com/writing/iberian.htm

Michelena, Luis, and Rudolf P.G. de Rijk. 2013. Basque language . Encyclopaedia Britannica. Available at: https://www.britannica.com/topic/Basque-language

Morandi, A., Pisani, V., Prosdocimi, A.L., De Simone, C., Watkins, C., Whatmough, J. and Zamboni, A., 106. Lusitanian.

Morato, Luis. N.D. The ‘Astronaut’ of Casar . Atlas Obscura. Available at: https://www.atlasobscura.com/places/astronaut-of-casar.

Prósper, B.M., 2014. Some Observations on the Classification of Tartessian as a Celtic Language . Journal of Indo-European Studies, 42(3/4), p.468.

Sinner, A.G. and Velaza, J. eds., 2019. Palaeohispanic Languages and Epigraphies . Oxford University Press, USA.

Strom. Caleb. 2020. Tiermes: Spain’s Ancient City Beset By Drama and Conflict . Ancient Origins. Available at: https://www.ancient-origins.net/ancient-places-europe/tiermes-0014366

“Tartessus.” 2016. Encyclopaedia Britannica. Available at: https://www.britannica.com/place/Tartessus

Watkins, Thayer. N.D. The Nature of the Basque Language . Thayer Watkins San Jose State University. Available at: https://www.sjsu.edu/faculty/watkins/basque.htm

Related posts:

Views: 0

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

October 23rd, 2020

October 23rd, 2020  Awake Goy

Awake Goy  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: