‘You cannot see him,” the little woman insisted through the small opening in the front door to the apartment. I stared at her and wondered who she was. Whoever she was, she looked determined. I stood frozen by indecision. Should I persist and try to convince the woman with my poor Czech to let me enter or should I give up, turn around, and walk away?It was fall 1995. My wife, Jean, and I had just spent three pleasant and relaxing weeks touring Portugal and Spain and landed in Prague. Now I wanted to take a day and visit Brno, my hometown, and fulfill a desire that had nagged at me for over 55 years. I rented a car and drove to Brno alone. That is how I ended up standing in front of the partially opened door trying to decide what to do next.Locating this apartment was not easy. Earlier in the morning, before leaving Prague, I had driven to the Interior Ministry, and got to the Personal Records Department. After a lengthy discussion with a clerk, I was finally able to convince him that I was not a bill collector, an attorney, or a person with sinister motives. I was simply trying to locate a person, a very, very old friend. I was certain, since the country had only recently been liberated from an oppressive Communist dictatorship, that every citizen’s whereabouts were carefully registered. I was not disappointed. After paying for a 20 Czech Crown tax stamp and waiting for about 20 minutes, the clerk handed me a form with the person’s address and all his vital statistics neatly listed.Knowing the address of the apartment was one thing but locating Mendlovo Namesti 13 was another challenge altogether. During the day I had to visit Adamov to meet with a business client. Then I decided to tour the beautiful wooded area north of Brno. So by the time I arrived at the Brno Holiday Inn it was dark. I then set out to search for the address that is located in the oldest part of Brno. Despite the poor lighting, I finally found the building.A large door, which in the past had been used to admit horse-drawn carriages into a courtyard, seemed to be the only way to enter. After a while I found a smaller door within the larger one. I pushed it open and found myself in a large dark courtyard. My eyes became adjusted to the darkness, and I was able to make out the open outside staircases and walkways that faced me on all four sides. I located a switch for the lights. I pushed the button and a few lonesome bulbs came to life. Which of the several staircases facing me should I take? Before I could decide, the lights went out. I pushed the button again and tried to locate a directory. No luck, there was none to be found. The lights went out again. I pushed the button and decided to proceed up the nearest staircase. Before I reached the first floor, the lights went out again. I searched and finally located another light switch. During the next period of illumination, I knocked on the nearest door. The door opened cautiously and in the best Czech that I could muster, I asked for directions. “Two more floors higher and to the right,” I was told.AFTER SEVERAL pushes of the light switch, I finally arrived at my destination and knocked. Only after my third, rather forceful knock, I heard some sound of motion in the apartment and, after a long while, the door opened a crack. In the dim light I made out the shape of a woman, perhaps no more than five feet tall with a pinched face that made her look a bit older than her years.

“Is this the home of Ladislav Kellner?” I asked. “Yes,” came the curt answer, “but you can’t see him.” The door started to close. It was time to decide what to do.

What has brought me to this point? I was going back 55 years to the last day before my departure to the United States. That afternoon in August 1940, my childhood friend Lada (as he was called by his family) came to visit me at Uncle Jacob’s house to say farewell. Today he was the last and only person who was still alive who could bridge for me the gap between now and the life of our family before World War II, before the Holocaust, before its horrible consequences. Could seeing him and speaking with him help me connect the present to the past, fill in the gap that has existed all these years between now and the day I left my birthplace more than a half-century ago? And if such a bridge could be formed, could it bring back some of the feelings, some sense of the life of my youth that the war destroyed?From inside the apartment a man’s voice was heard. The little woman turned her head to the side and shouted something back. I stood in front of the door waiting for something to happen. The woman looked back at me. “He’s a sick man,” she whispered, “he has sugar.” Then, slowly and still reluctantly, she opened the door wide enough for me to enter. The door closed behind me and I was standing in the middle of a kitchen. To my right was a small gas stove with some shelves mounted on the wall. Boxes, cans, jars and cooking utensils were stacked on the shelves. One shelf held a motley collection of dishes that obviously had come from various sources. In the corner was a stack of cardboard boxes and plastic bags. Against the back wall was a cabinet badly in need of painting. To my left was a doorway and a table with three chairs set under it. The walls and ceiling looked like they had not been painted in decades. The whole scene was lit by a bare bulb hanging from the ceiling.The woman walked through the doorway to my left without saying a word. I stood in the room waiting. Suddenly I was flooded by great doubts about whether I should have made this visit. When I last saw Lada he was 14 years old. He was a good-looking teenager, a head taller than I, thin, and with a typical round Slavic face. After the war we would correspond on and off and I would receive pictures and postcards from him. The pictures showed a handsome young man looking back at me. Then, after a while, we stopped writing and the contact was lost for nearly 50 years. Nevertheless, Lada always occupied a warm spot in my heart. ALL MY Czech friends abandoned me when the Nazis marched into Czechoslovakia, Lada remained a good friend until the day I boarded the train that, ultimately, brought me to the United States. When I decided to make this visit, I wasn’t sure what I would find. Now that I stood in the middle of the kitchen of this ancient apartment, I was filled with anxiety.Just then I heard shuffling footsteps to my left. I turned toward the doorway. Will I recognize Lada? Will he recognize me? Will he even remember who I am? The questions were racing through my head. It had been such a long time, so many things had happened, so many years had gone by. In the 55 years since I had last seen Lada, a third generation of the Ticho family had been born, matured, and some had already passed away. I looked to my left as the footsteps came closer. Then, through the door, walked a very old man. It shocks me to write this, but that is really the only fair way to describe what I saw. I searched the face desperately to find a trace of the 14-year-old boy I had last seen or the young man that had stared at me in the photographs I had received from him. There was not the slightest resemblance. It was obvious that he had just hastily put on some clothing and slippers, neither of which were very clean. I stood there in my London Fog winter coat and the Hermes silk shawl that Jean’s cousin Mira had given me in Paris and felt very much out of place.The man looked at me quizzically, and not even my name, repeated several times, seemed to explain to him who I was. After several very awkward minutes, Lada asked me to sit down at the table. I believe this gesture was not as a result of politeness, but rather because he could not stand too long at any one time. I reached into my pocket and withdrew an envelope. I had saved the postcards, the photographs and letters that I had received from him and brought them along. Slowly, with trembling hands, Lada flipped through the pictures and read his own letters and postcards. I realized that I was really hoping for too much. I should not have expected that this man could have a stranger walk in on him one evening and remember him after 55 years. LADA WITH his parents after the war, having survived a serious infection thanks to the penicillin the writer sent him. (Courtesy Charles Ticho)Nevertheless, slowly the veil of time was drawn back and there was a spark of recognition in Lada’s eyes. His mind rolled back to the years before the war, and our conversation was beginning to flow easier. For the next hour or so we sat and talked. Lada and his family remained in our building throughout the war. Our apartment, which was seized by the German General Braunau von Trillingen, remained in their hands even after he was killed on the Russian front. Our governess lived for a few months in our apartment on the second floor but disappeared when another German Army officer moved into the apartment. Both German families cleared out of the apartments and disappeared a few weeks before the Germans surrendered. The apartment stood empty until the end of the war, when the Czech authorities took possession of the building and assigned Czech families to live in them. Our large apartment was subdivided and three families moved in.AFTER THE WAR, Lada became very ill and he was certain that the penicillin that we sent to him saved his life. When his father died, his mother could no longer handle the janitorial duties in the building and Lada was not interested in such a job. His mother moved back to their hometown, Ivanovice, and Lada lived alone for a while. He lost contact with our building when they moved out. He got married to the woman who was now watching television in the next room. They had two children, but his daughter died at the age of 24. His son had two sons, so, he told me proudly, the Kellner name will live after he dies. His life had not been easy. He worked for most of his life at the large plant known locally as Zbrojovka. This company produced a vast array of machine products ranging from cannons to motorcycles. Now that he was suffering from diabetes, he was receiving a small pension.Then, it also became my turn to answer his questions. He was pleased to hear that my father had lived to a ripe old age. He remembered that I had a brother in America. What happened to him? I told him about Harold and his work at the University of California. I had much greater problems trying to explain what I do. I finally settled the matter by claiming to be an engineer in television. Ultimately we came to the question that I had feared: “You had a little brother. How is he doing?”I struggled with the answer for quite a while. How was I going to explain to this man how and why my wonderful, talented, successful, kind, considerate and generous brother, the father of three wonderful daughters, a highly regarded attorney and a successful real estate developer, was murdered in his sleep? Slowly, I told the story as best as my poor Czech and my heavy heart would allow. When I mentioned that it had happened in Chicago, Lada understood. “Yes,” he said knowingly shaking his head, while pretending to be shooting a machine gun, “Chicago, gangsters.” I left it at that. Further explanations were not really necessary.By then, Lada’s wife had wandered back into the kitchen. She stood there behind her husband listening to our conversation. The belligerence had disappeared from her face, and she was obviously very interested in what we were saying. When I started to tell Lada what had happened to some of our relatives in the German concentration camps during the Holocaust, how many had died and who had survived, she became a little puzzled. “What,” she asked her husband, “are you talking about?”As I left Lada’s apartment, never to see him again, I stopped at the top of the steps and stared into the darkness. “How could this woman,” I asked myself, “know nothing about the Holocaust?”It had been a very difficult and sad evening in many ways.

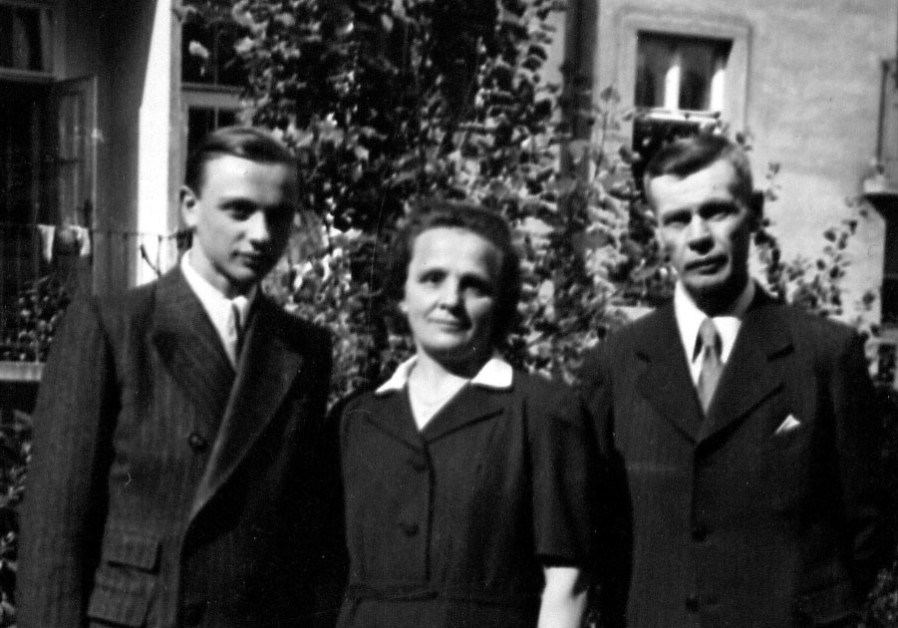

LADA WITH his parents after the war, having survived a serious infection thanks to the penicillin the writer sent him. (Courtesy Charles Ticho)Nevertheless, slowly the veil of time was drawn back and there was a spark of recognition in Lada’s eyes. His mind rolled back to the years before the war, and our conversation was beginning to flow easier. For the next hour or so we sat and talked. Lada and his family remained in our building throughout the war. Our apartment, which was seized by the German General Braunau von Trillingen, remained in their hands even after he was killed on the Russian front. Our governess lived for a few months in our apartment on the second floor but disappeared when another German Army officer moved into the apartment. Both German families cleared out of the apartments and disappeared a few weeks before the Germans surrendered. The apartment stood empty until the end of the war, when the Czech authorities took possession of the building and assigned Czech families to live in them. Our large apartment was subdivided and three families moved in.AFTER THE WAR, Lada became very ill and he was certain that the penicillin that we sent to him saved his life. When his father died, his mother could no longer handle the janitorial duties in the building and Lada was not interested in such a job. His mother moved back to their hometown, Ivanovice, and Lada lived alone for a while. He lost contact with our building when they moved out. He got married to the woman who was now watching television in the next room. They had two children, but his daughter died at the age of 24. His son had two sons, so, he told me proudly, the Kellner name will live after he dies. His life had not been easy. He worked for most of his life at the large plant known locally as Zbrojovka. This company produced a vast array of machine products ranging from cannons to motorcycles. Now that he was suffering from diabetes, he was receiving a small pension.Then, it also became my turn to answer his questions. He was pleased to hear that my father had lived to a ripe old age. He remembered that I had a brother in America. What happened to him? I told him about Harold and his work at the University of California. I had much greater problems trying to explain what I do. I finally settled the matter by claiming to be an engineer in television. Ultimately we came to the question that I had feared: “You had a little brother. How is he doing?”I struggled with the answer for quite a while. How was I going to explain to this man how and why my wonderful, talented, successful, kind, considerate and generous brother, the father of three wonderful daughters, a highly regarded attorney and a successful real estate developer, was murdered in his sleep? Slowly, I told the story as best as my poor Czech and my heavy heart would allow. When I mentioned that it had happened in Chicago, Lada understood. “Yes,” he said knowingly shaking his head, while pretending to be shooting a machine gun, “Chicago, gangsters.” I left it at that. Further explanations were not really necessary.By then, Lada’s wife had wandered back into the kitchen. She stood there behind her husband listening to our conversation. The belligerence had disappeared from her face, and she was obviously very interested in what we were saying. When I started to tell Lada what had happened to some of our relatives in the German concentration camps during the Holocaust, how many had died and who had survived, she became a little puzzled. “What,” she asked her husband, “are you talking about?”As I left Lada’s apartment, never to see him again, I stopped at the top of the steps and stared into the darkness. “How could this woman,” I asked myself, “know nothing about the Holocaust?”It had been a very difficult and sad evening in many ways.

Source

Related posts:

Views: 0

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

January 14th, 2021

January 14th, 2021  Awake Goy

Awake Goy  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: