On my first night in an Israeli settlement, David served chicken soup left over from Sabbath at his daughter’s house and told me an unsettling story about the birth of Israel. His great uncle had escaped Europe to come to a Jewish kibbutz called Ein Harod. On the next hill was a Palestinian village. When hostilities broke out between Jews and Palestinians in 1948, the Jews went up to the village and announced that the next day they were bringing bulldozers to level the place, the people should leave. The next day they went back and were surprised to find that the Palestinians had all fled– fearing a massacre like the one that took place in Deir Yassin. The Jews then leveled the village and used the stones to build a stadium in their kibbutz. David said his uncle had told this story “with a twinkle in his eye.”

David was not the only settler to tell me stories of the Nakba. And the meaning was clear: A previous generation of Zionists had done terrible things to Palestinians in order to build the state of Israel. Now David and the other settlers were taking that same project– Zionism, the renewal of the Jewish people in their land—to the next part of the land of Israel. And they were doing so without destroying Palestinian villages, as their socialist predecessors had done.

The settlers told me that the great political development of the last year or two is that the Tel Aviv elite now concede that the settlers are never leaving. The elites give lip service to a Palestinian state because the world wants to hear that. But few in Jewish Israeli society even want that to happen; it would tear the country apart.

I spent five days in the settlements in mid-January using the Airbnb service. My original plan was to expose the fact that Airbnb is doing business inside the occupation. But that story broke when I got to Palestine (with Jewish Voice for Peace and others calling on the company to end the service). I went through with my bookings because I have always been curious about settlers. I slept in four settlements and visited a half dozen others. I ate with settlers and prayed with them. I saw a bris and a bar mitzvah. Half my hosts were American-born, half were Israeli. I gave my real name to my hosts, but I misrepresented myself, saying that I sell houses in New York (I have supported myself in part by flipping houses), because it was clear that I would never be accepted in these places if I was forthcoming. The settlers are engaged in what the world sees as illegal activities, and imposture was the only way for me to get this story. All my hosts were kind to me; I am masking their identities.

I learned more about Israel in those five days in Palestine than in any other trips I’ve made. These colonies were founded a generation ago with the aim of creating one state between the river and the sea and they have succeeded. They are fortresses built with Palestinian labor. Today the mass of Israeli Jewish society does not want a Palestinian state, these settlers say; and the colonists would rise up in the hundreds of thousands before allowing such a state. This is the reality that high State Department officials have sought to convey to the American public– but that our press has failed to tell us.

The world I visited is the world that Zionists made, according to their ideal of Jewish sovereignty. And it is a world of segregation, with Jews on top. One fact leaps out from my tour. In five days of moving in and out of settlements in occupied territories and making four trips back to West Jerusalem inside Israel by bus and hitchhiking, I never had to produce my passport. Not once. Because I was with the whites, in white cars. I have visited occupied Palestine countless times with Palestinians; I am almost always asked to produce my passport at checkpoints.

1. Gush Etzion bloc

David is tall and wiry and weatherbeaten, in his late 60s and lives in a shack on a hillside and wears khakis begrimed by physical labor and a “cowboy” revolver slipped into his belt under the down vest. He grew up on Long Island and could have had a much better life in the U.S. He says that he lives on the edge of the Judean wilderness, and he can walk to the Dead Sea in a full moon in 12 hours. “They call it Judea. That means it is the land of the Jews. This is where a Jew belongs, that’s my view.” His house is held together with baling wire. He doesn’t care about money, he cares about children. He has five by his ex, and a couple of years ago he married an immigrant from Russia in her 30s after she converted to Judaism. It didn’t work out but when I ask him how many children he was going to have with her David says, “Double digit.”

He drives me around three hilltop settlements in a rickety car and points out a salient covered with new redroofed houses. “Are you sitting down? That’s the Tekoa housing boom– because of the settlement freeze!” He says the 2010 freeze allowed construction on houses that were already started; so before it went into effect, crews worked day and night with lights to get scores of foundations in.

View north from Nokdim settlement in Gush Etzion bloc. Tekoa settlement is at left. In center foreground is security camera; in right background the Herodium. (Photo: Philip Weiss)

The construction workers were Palestinian. As we drive in and out of Tekoa, David waves to a Palestinian man in a new pickup. Ahmed is shuttling work crews from job sites inside the settlement to their cars in a lot outside. They can’t walk or drive through the settlement; they must get a day-pass from security and a ride. Ahmed has a pass to bring his car into the settlement. Ahmed lives in “Arab Tekoa,” David says. “You can always tell the Arab villages by the phallic symbol. The minarets.”

David works as a security guard for Ahmed and other Palestinian contractors, because all Palestinian workers must be accompanied by an armed Israeli. It is for the peace of mind of the Israeli women in the settlement, perambulating their children. So David sits in a chair with a book and his gun all day as Ahmed’s workers set cinderblock and plaster walls. He makes 300 shekels a day, the same as a master craftsman.

Sometimes the homeowner pays for him, but more often the contractor. David said to Ahmed: “Do you see how absurd this is? You pay me… To protect someone else… From you!”

There is an innocence about David I find appealing. Back at his house we open a bottle of settler wine, and he agrees that it is wrong that Ahmed can’t vote and he can. That’s why the Israeli government built the wall inside Palestinian territories, he says. It’s not a security fence: it provides no security to hundreds of thousands of settlers on the Palestinian side of the wall who would be the “juiciest” victims if the Palestinians really wanted to kill them. The purpose of the wall—in the view of the Israeli establishment, David says — is to keep down the number of “filthy Arabs” who will someday be able to vote inside greater Israel.

A bottle of settler wine in David’s kitchen in a Gush Etzion settlement. (Photo: Philip Weiss)

David says the elites in Tel Aviv don’t like the settlers because the settlers expose the fact that they did far worse for the same Zionist goals. “700,000 Palestinians fled their villages in 1948– why?” David asks me. “The official version is that the Arab committee in Damascus issued orders for them to leave that went out on loudspeakers, and the villagers up and left.” But that’s nonsense. The Palestinians fled in fear after the massacre at Deir Yassin.

David also excuses the Zionist militias of massacres. They were trying to secure the road to Jerusalem, and were under attack. “Of course we fought back. We’d just gone like lambs to slaughter in Europe.”

I ask David why we need a Jewish state. David tilts his head and looks at me oddly, like I said the earth is flat.

“Come on?! After the Holocaust?”

He builds a fire in the wood stove and shows me a video of a Jew in the US army fighting the Nazis. He reads a lot about the Holocaust. “1.5 million Jewish children. Imagine that. 1.5 million.”

I tell him what my mother said about why she had six children. “One for each million.”

David claps his chest. “Did she really? That sends a shiver up my spine.”

We drink more wine and he tells me of his own motivation. It was 1973, the Yom Kippur War. He had security clearance in the US army and his commanding officer told him that Egypt and Syria were going to invade Israel two days before it happened. David saw that the US was not sharing all it knew with Israel, and he was on the wrong side. When a polygraph operator asked him if he would ever share secrets with a foreign country, he said, “No,” and the operator said, “You had trouble with that one.” David realized he was right and he should leave the country, and help secure the Jewish state.

I ask him why people call these illegal settlements?

“Because the world has always hated Jews,” David says. He tells me of his experience of anti-Semitism in the United States. He had a good gentile friend who one day commented about a jeweler, “He’s a Jew, in the worst sense.” David says, “When I heard that something inside me died.”

Though David reflects that if he weren’t Jewish he would probably be anti-semitic. “Because we’re a clannish group that outdoes you.”

The chicken soup from Sabbath three days ago is stretched with cut-up hotdogs and chicken necks. As we eat, David shows me a flyer in Arabic distributed by the “Associazione Musulmani Italiani” that he has had copied by the gross because he thinks it can Muslims. It is part of his program for de-Islamification.

“What does de-Islamification sound like?” he says.

I can’t guess, and he says: “DeNazification.”

Flyer on Islam that a settler distributes to Palestinians in his campaign for “de-Islamification” (Photo: Philip Weiss)

If the world had stopped the Nazis in the 30s, it would have saved 70 million lives. The same opportunity is available to us now. I tell David I don’t think that Jews and Zionists are going to be able to force changes in another religious culture. David says it’s the only way to peace. Palestinians will be allowed to vote once they accept that Israel is a Jewish state. They can’t accept that under Islam.

I get ready for bed. This is frontier life. There are compound buckets filled with gray water from the washing machine that you put in the toilet tank to make it flush.

In the morning David toasts bread on top of the wood stove and serves it with instant coffee. Sitting down, he gives me a sweet smile. “What your mother said about the 6 million– that was a beautiful statement.”

David’s son has borrowed the car, so we walk to a bris at Nokdim, a neighboring settlement. We have to walk out past heavy steel security gates and a guard in a booth. She’s Russian. A lot of the Russians are not Jewish, David says, or they have one grandparent who’s Jewish. To get married in Israel they have to convert, but the official rabbis don’t accept a lot of the conversions.

Avigdor Lieberman’s house can be seen at the back of this photograph in Nokdim settlement in Gush Etzion bloc in Palestine. (Photo: Philip Weiss)

Our trip takes us past the houses of two famous members of Knesset: Avigdor Lieberman, former foreign minister (and an immigrant from the former Soviet Union), and Ze’ev Elkin, a minister in the Netanyahu government who brought down the last government by putting forward a bill stating that Israel is the nation-state of the Jewish people. At the gates of Lieberman’s settlement, two Palestinian workers are standing waiting for their day passes. They probably live in a nearby village. I live thousands of miles away but I saunter in with David with a mere nod from the guard. The two workers are to be ferried to the jobsite by a contractor named Mahmoud, whose car is authorized. His hands are covered with stone dust. David also works for Mahmoud. He stops to chatter with him in Hebrew about the Italian Muslim leaflet. Mahmoud says that 40 percent of the people he’s given it to are persuaded.

As we walk away David says it was “the hand of God” that Mahmoud was there when we came up.

Look closely and you can see Palestinian workers at this job site inside Israeli settlement Nokdim. At center right several of them are seated, having a break, January 13, 2016. (Photo: Philip Weiss)

The bris is at a modern synagogue built into the hillside beside a high security fence mounted with cameras to monitor the perimeter. Several Americans of David’s generation are at the bris, and David wears a Nefesh b’Nefesh hat—from a program that gets American Jews to move to the occupied territories. One guy admires David’s cowboy gun, and a bearded guy from Colorado tells me that in every Jew’s life he will hear a call to join his people. Abraham got it in the land of Haran; he had to move his family to Canaan.

“Was that what my grandfather heard in Russia, when he came out to America?” I say.

“No. That was Get the hell out of here!”

The bearded guy says the call is deep in your brain. “It’s like a salmon being out in the ocean doing fine, then something goes off in his head and he turns around and swims upstream, past dams and Indians and bears– it doesn’t matter.”

“Salmon– that’s good,” David says. “I always thought of lemmings.”

“No; stay away from lemmings,” his wise friend says.

Both grandfathers of the object of the bris are American. The redheaded one tells me he went out to South Africa in 1986 with the Jewish Agency to bring Jews to Israel. “The blacks were rising up,” he says.

“Doesn’t that happen here too?” I venture.

“No. We’re the natives.”

A young guy interrupts us to make circumcision jokes. “Can you get half off? Will you keep the tip?”

The grandfather comes back at him. “How do you circumcise a whale? Four skin divers.”

I slip out before the fateful act. David and I hug one another goodbye and I wait at the bus stop for all of 30 seconds before an American-Israeli in a suit and a yarmulke stops. This is what Israelis call the trampiada, the hitching spot. He drives me fast into West Jerusalem.

A gray fox crosses the road and I tell the driver about the political understanding I’ve gotten from one night in Gush Etzion: liberal Zionists divide Israeli history into a noble portion of 19 years from 1948-1967 and a shameful portion of 48 years since; but that’s wishful thinking, it’s all one Zionist process of putting Jews on the land.

“You have it exactly right,” he says. “Though what you’re leaving out is that Jews have been coming to the land of Israel for millennia. In fact, to say Jews shouldn’t be allowed to live in these places is a form of anti-Semitism.”

“What about the two state solution?” I ask.

“Who talks about that anymore? Obama even has given up on it. In what’s left of his administration, it’s over.” He says the elites still pretend to support it. “Even Netanyahu.” They have a plan, in which a few hundred thousand people would be uprooted from these communities. But he says there would be a massive rebellion if that ever happened.

View to the west from kibbutz Na’aran in the Jordan Valley. Beyond security fence is the wadi and Judean hills. (Photo: Philip Weiss)

2. Na’aran, the Jordan Valley

My second settlement has a different ideological flavor than the first, and even more beautiful views. It is a hilltop kibbutz below sea level in the Jordan Valley. To the west we look up at the Judean mountains guarding Jerusalem. To the east we can see the Jordan River delta and the lights of Amman. In the foreground: a date palm plantation owned by the kibbutz, and a factory that makes plastic films that a member of the kibbutz says proudly employs lots of Palestinians (and that Human Rights Watch will call on to leave the occupation)

Like the early kibbutzes in the Galilee, this kibbutz has a fortresslike character. It is composed of a ring of hutlike structures on the hilltop. My host shows me to one of them. We walk down pathways that intertwine the huts, and he tells me I don’t need to lock my door, none of the wifi networks needs a password, and I can go anywhere I like in the kibbutz, though my walks will end when I come to the high fence topped with barbed wire, with a second and third perimeter of rolls of concertina wire.

Walking the perimeter of kibbutz Naaran at night. Note the spools of concertina wire behind the fence. (Photo: Philip Weiss)

My host brings me a dish of fresh dates, then has to leave for Tel Aviv for a teaching job. The kibbutz is the home of a Zionist youth movement dedicated to education. The kibbutz had been abandoned ten years ago when HaMahanot HaOlim took it over. The young people haven’t fully recolonized the place. Many of the huts are empty, and a lot of the flower-power debris from the first kibbutz is still strewn around the place: pink trucks and chicken-wire radio receivers.

Old roadbuilding equipment at kibbutz Naaran in Jordan Valley, Palestine. (Photo: Philip Weiss)

The HaMahanot kibbutzniks are more like me than any of the settlers I meet during my tour. They are secular professionals with liberal ideas, their recycling bin is overflowing with red wine bottles. Yet they are also Jewish nationalists. They are building the Jewish community in the land of Israel. “Original Zionist,” my host tells me. “We are not religious but we celebrate the Jewish holidays in our own non-traditional ways.” In Wikipedia, I learn that the youth movement has been thrown out of an international socialist group because it still operates in occupied territories.

Of course, there are no Palestinians in the kibbutz. Though there is a hut filled with Thais. On my walk, I see a flatbed truck carrying a dozen of them back from the plantation. As the sun is setting I walk into their yard. They are having an outdoor fire at 5 o’clock, but I’m definitely not welcome. They are skinny and tired-seeming, a couple look at me with frightened faces. The old ideal of Jewish labor has given way to neoliberal globalization.

After dark I walk up to the kibbutz dining hall. The door is open but it is completely empty. I’m saddened. Communal life is the reason Bernie Sanders, Tony Judt, Arthur Koestler and Noam Chomsky came out to this country. Now that’s the past.

Zivia Lubetkin, Warsaw Ghetto heroine, picture in the office of HaMahanot Haolim kibbutz in occupied territory. (Photo: Philip Weiss)

I’m using the internet in the breezeway outside the office when a slender Israeli in a hoodie comes up with two M16s crammed under one arm. He is the head of security, he says affably, but the guns are evidence of the place’s intense security needs. On my night walk, I will go to the front gate and chat with three Israel Defense Forces soldiers next to a sliding steel barrier big enough to stop a truck. The kibbutz’s own neighbors don’t really want it here. Koestler describes building tower-and-wall outposts like this in his 1930s memoir of Zionist colonization of the Galilee.

I talk to a few of the kibbutzniks. They all say they would leave the Jordan Valley if the government asked them to, to make way for a Palestinian state, but when you scratch the surface, they don’t believe in a Palestinian state any more than the more conservative religious Jewish settlers I’ve met.

“I am a leftist, but the two state solution is problematic,” says a burly thoughtful kibbutznik. “They won’t have an airport– they can’t, it won’t happen. They won’t have a seaport, except through Israeli control.” The only way for Palestinians to gain real sovereignty is to share portions of the West Bank with Jordan. That’s an idea you hear from rightwing Zionists all the time. He says that a “tongue” of land would connect the Palestinian villages on the West Bank hills with Jordan. And another tongue would connect Israel to the Jordan Valley; his country would need to keep a force here to preserve not just Israel but Jordan and progressive elements of Palestinian society from Islamists.

“Jordanian soldiers don’t face us, they face east. ISIS is just 50 or 100 miles away,” he says.

A kibbutnik who is playing with his child near a steamroller from olden days brings up Jewish settler violence. Duma, the village where three members of the Dawabshe family were murdered by settlers last summer in a firebombing attack, is just a few miles over the hills to the northwest. And then there is that rabbi’s book called the King’s Torah that justifies the killing of gentile babies, if they might grow up to hurt Jews. The rightwing intolerance makes him despair, he says.

“We want a future with hope,” he says.

“What if that hope is a democracy that’s not a Jewish state?” I say.

He shakes his head. “No. We need a Jewish state. History shows– the Second World War. But Palestinians must not be second-grade citizens. Israel can be like the Vatican. There are non-Catholics living in Vatican City, and they have rights.”

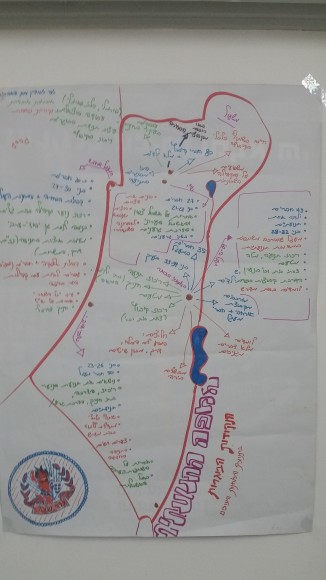

Even liberal Zionists think it’s one state. This is the map on the office wall of socialist kibbutz Naaran, operated by the HaMahanot HaOlim youth movement. (Photo: Philip Weiss)

That night I’m walking around the kibbutz perimeter road when I have a classic kibbutz experience. On a wall by a hut I see the cowering silhouette of a dog watching me. Then a minute later it has attached himself to me! The dogs here are communal, but I use the lost-dog excuse to say hello to two women sitting out on their porch by a woodstove. One of them is very friendly. She invites me on to the porch and makes me tea from a verbena plant and tells me about her years in the U.S. southwest in an Israeli diplomatic family. Funny and wise and aware of the outside world, this young woman is the most sophisticated person I will meet in my five days in settlements.

I say, “But do we really need a Jewish state?”

“Don’t start that! I’m not a Zionist.”

We both laugh. Then she vents some universalist ideals about the end of identity politics, as I nod my head. I never ask her what she’s doing in an exclusively-Jewish community; but I find the conversation restorative. Some Israelis understand that Jewish nationalism isn’t working out.

Though the next morning my settlement malaise sets in again. I’m out for another walk when I hear children’s voices ringing across the land. I walk toward the cries, hoping to see the kibbutz kids playing together. I pass the dump from the last kibbutz and the installation of ET-style radio receivers, but the voices continue to echo without getting any closer.

Then I see it’s Palestinian shepherds on horseback in the wadi far below, calling out to one another as they bring their flock up the slopes. They are a half mile away, but as I come closer to the fence, they gallop away round a stony outcropping out of sight. I feel imprisoned. They are much freer on this land than my hosts.

This is the first of two parts. The second part will run tomorrow.

Source Article from http://mondoweiss.net/2016/01/among-the-settlers

Related posts:

Views: 0

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

January 25th, 2016

January 25th, 2016  Awake Goy

Awake Goy  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: