In 2011, three nuclear reactors melted down, provoking a series of hydrogen explosions and resulting in the world’s most severe nuclear accident. It happened in Japan, which had been long celebrated as a technology powerhouse.

Advertisement

At the time of the accident, the site became a veritable death trap, with extremely high levels of radioactivity and chunks of concrete from the explosion raining down on workers. And yet, there were some who remained on the ground to try and bring the overheating nuclear power plant to a halt.

“I just couldn’t run away when my country was about to sink,” one of the workers said. If this story can be told at all, it is precisely thanks to those who faced one of the world’s worst nuclear disasters out of a sense of pride in their country’s technology, attachment to the community and loyalty to their jobs.

The magnitude 9 Great East Japan Earthquake struck at 2:46 p.m. local time on March 11, 2011. Soon after, a large tsunami hit the ground level of the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant, which consisted of six nuclear reactors.

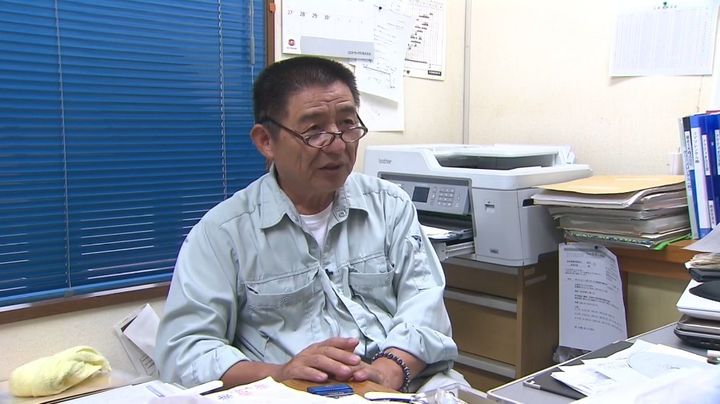

Satoru Umematsu, a veteran electrical engineer who had taken part in building the ground floor, was there when it happened. Umematsu was 60 at the time, and fast approaching retirement age.

Advertisement

When the nuclear power plant’s power transmission tower was knocked down by the force of the earthquake, causing the loss of external power supply, emergency generators kicked in, ensuring that cooling pumps could continue to function.

When the tsunami struck, however, the emergency generators of reactors 1 through 4, located about 33 feet (10 meters) above sea level, were flooded and stopped working.

When Umematsu rushed to the plant’s earthquake-proof building, about 115 feet (35 meters) above sea level, where the emergency response room was set up, it was packed with people. Inside, ashen-faced power plant executives were bustling around in a frenzy.

A Strategy Forms

Advertisement

As Umematsu and the others realized that the reactors could no longer be cooled down, they moved to secure a vehicle-mounted generator and power cables in order to generate electricity and restore the power supply.

“It was unimaginable that a nuclear power plant would lose all power. So, when it did actually happen, we were overcome by a tremendous sense of urgency,” he said.

For Umematsu, who had experienced all kinds of situations at different job sites in the course of his career, this crisis was an absolute first.

After graduating from junior high school and acquiring engineering skills at a vocational training center, Umematsu had accumulated over 40 years of experience in electrical construction sites, including power generation dams and nuclear power plants. He was familiar with most electrical systems in nuclear power plants. He was proud of the technological capabilities Japan had acquired after World War II and would proudly tell his relatives of his work at the nuclear power plant. He was relied upon by subordinates and colleagues, who respectfully referred to him as “Ume-san.”

Fukushima Central Television

In order to complete their task in the shortest possible time, Umematsu and his crew devised a simple strategy. To restore the power supply, they would park the vehicle-mounted generator next to the reactor building and link it to the nuclear power plant by connecting the power cables.

Opening A Path For The Truck-Mounted Generator

However, even the task of moving the truck-mounted generator closer to the reactor building was a daunting one. All kinds of debris and rubble brought by the tsunami littered the area around the reactor building, obstructing the passage of vehicles.

It wasn’t the power plant staff, the Self-Defense Forces, the fire department, nor the police who tackled this problem — it was a local resident.

Yoshishige Tochimoto was the managing director of a local company with about 10 employees. He was 51 at the time. When the earthquake struck, he witnessed the destruction of the nuclear power plant’s critical equipment.

Fukushima Central Television

“When the power transmission tower on the slope was brought down by the earthquake, it generated huge sparks. They were pink in color. Between 10 to 20 meters in length,” he said.

Advertisement

Fukushima Central Television

Tochimoto was on the premises as a subcontractor, doing seismic retrofitting work on the nuclear power plant. As he felt the ground shaking, he said he was unable to stand on his feet.

His own car was washed away by the tsunami that followed the earthquake. Luckily, his company’s excavator had suffered virtually no damage and only the caterpillar tracks had been submerged.

Wary of being exposed to radiation, Tochimoto had not actively sought out nuclear-related work in the past. But now he accidentally found himself on the scene of a nuclear disaster.

“This could be really bad, I thought,” he said.

‘I Won’t Be Gone For Long’

Workers from Tochimoto’s business and other local companies assembled in the parking lot in front of the earthquake-proof building.

They took a roll call to ensure everyone was safe. Then, the prime contractor company instructed them to “disband,” as it was feared that some of the workers would have lost some family members, or their homes would have been damaged. Tochimoto remembered what the other workers were talking about at the time.

“There was talk of opening a vent hole to prevent a hydrogen explosion,” he said.

A hydrogen explosion. He was unfamiliar with that word. The matter, however, seemed completely unrelated to him.

Fukushima Central Television

Worried about his wife and children, he decided to go back to his home, approximately 8 miles (13 kilometers) away. Since his car at the nuclear power plant had been washed away by the tsunami, he asked an acquaintance for a ride home.

Advertisement

What would normally be a 30-minute ride ended up taking them two hours, as the road was heavily congested with people evacuating. After getting home and making sure that everyone in his family was safe, he got a call from the prime contractor company.

“Will you help us fix the nuclear power plant?”

Fukushima Central Television

The roads inside the nuclear power plant were impassable by vehicles as they were covered in rubble and fissures in the asphalt had caused uneven gaps. Tochimoto thought that, if it was only a matter of fixing the road, it would not take long and he would be back home soon.

“I won’t be gone for long,” he told his family as he headed toward the Daiichi power plant. The time was around 7:30 pm.

Restoring Power, Fighting Against Fear

It took until nighttime to prepare the equipment needed to restore power. With preparations over, Umematsu gathered some young workers from the power plant and explained to them how to handle the power cables and how to route them.

The cables in question were special high-voltage cables called “Triplex,” which could suffer damage if dragged over the ground. The workers would have to connect the heavy cables, each 1-meter section weighing about 13 pounds (6 kilograms), from the truck-mounted generator parked outside the building to the power panel inside. Due to the building’s complex structure, they would have to lay the cable over a distance of about 130 meters. Many of the team’s members had no previous experience in handling that kind of equipment.

“As graduates of Japan’s most prestigious universities, they knew the theory, but had never actually connected a high-voltage cable. I was the only one who could tell them how to go about it.”

Fukushima Central Television

However, at around 11:00 p.m., radiation levels several tens of times higher than usual were detected inside the building of the Unit 1 reactor. The pressure on the steel “containment vessel” enclosing the reactor holding the nuclear fuel was about to exceed the permissible values. The director of the power plant immediately forbade anyone from entering the Unit 1 building. The signs were unmistakable that the feared meltdown had begun.

If the workers did not complete the operation swiftly, they too could have been exposed to lethal doses of radiation. If only the power supply could be restored, the looming crisis could be averted. It was up to Umematsu to make it possible.

Advertisement

“I’m pretty sure we were all scared. Extremely scared,” he said. “But being scared is different from being hesitant. Some were actually hesitant and did not want to go. We were certainly scared. Incredibly scared. After all, we were going to an unknown site. However, while being scared, we behaved normally.”

Fukushima Central Television

Since Umematsu was not a regular power plant employee, normally he would have been advised to go home. Instead, the power plant managers, relying on his skills, asked him to stay. Umematsu could have walked away while he still did not know how much radiation he would be exposed to. Instead, he chose to listen to his heart.

“I knew my skills were about to be put to the test,” he said. “I was glad my know-how could be of help in such a situation. When your country is as likely to stay afloat as it is to sink, you can’t quit just because you’re scared or because radiation levels are high.”

At that point, he still hadn’t been able to contact his wife and children. Nonetheless, as an engineer, he decided to throw himself into the task and went to work near the reactor building.

An Unsung Achievement

The truck-mounted generator, however, was still a long way away from being able to approach the reactor building. The road had yet to be repaired in order to make that possible. Fissures in the road caused height differences as much as a meter high. Tochimoto’s team studied the situation and considered what to do.

A proposal was made to bring in gravel from a nearby quarry to fill in the gaps, but was abandoned because it would have taken too long. Tochimoto thought that, as long as vehicles could pass, anything would do.

When he tried to turn the key to his company’s excavator, the engine came to life. Using the tip of the excavator’s bucket, he began to strip the asphalt coating in the parts of the road where the gaps were. He then proceeded to remove the gravel from under the paved surface and to press the surface down so as to create a gently sloping incline, at which point it looked as if a car might just be able to go through.

Fukushima Central Television

“While I was trying to open a road with the excavator, most of the people were actually watching me,” he said.

It seems that it was only thanks to Tochimoto and his excavator that the road was fixed. In just three hours, working by himself, he managed to repair the road inside the nuclear power plant so that vehicles could reach the reactor building.

Advertisement

Had Tochimoto not been there, it wouldn’t have been possible for the truck-mounted generator to approach the building to restore power, nor for fire engines to reach the same building and try to cool down the reactor.

To this day, most people are unaware of his achievement.

Because the road was fixed quickly, vehicles were able to reach the area around the reactor building by midnight. In the following hours, Tochimoto joined forces with workers from other companies to remove the rubble scattered around the reactor building.

A week after the accident, when a Hyper Rescue Team from the Tokyo Fire Department entered the area to cool off the fuel, one of its leaders said: “We were utterly surprised to see how the area surrounding the power plant had been cleared of debris to the point that not a single stone was visible, and our vehicles were able to approach without a hitch.”

Fukushima Central Television

The Real Risky Work Begins

Around midnight, a movable generator and a truck loaded with high-voltage cables smashed the nuclear protection gate and headed toward the reactor building.

Directing operations was Umematsu, the veteran engineer. He was hoping that, by connecting the movable generator to the power supply point near the Unit 1 reactor building, power could be restored, and the cooling pumps could start functioning once again.

The power cable was laid out near the reactor building, where radiation levels kept rising. The riskiest part of the work was about to begin.

Fukushima Central Television

Their efforts, however, had to be repeatedly interrupted as magnitude 4 and 5 aftershocks followed one after another. After a tsunami of such enormity, it was only natural that the area would have to be evacuated every time a tremor hit. Umematsu was getting impatient.

“We could have restored the power supply in five or six hours. However, we had to stop working and leave every time an aftershock struck, so things hardly moved at all. We went at it all night long, but most of the time we were sitting on our hands,” he said.

Advertisement

Radiation Levels 30,000 Times Higher Than Normal

A few hours have passed. At a press conference at 3 a.m. on March 12, Yukio Edano, chief cabinet secretary at the time, announced that he instructed workers to open a vent to release the pressure accumulated inside the Unit 1 reactor. Unless internal pressure is lowered in the reactor, he explained, the entire steel pressure vessel enclosing the nuclear fuel will explode. If that were to happen, huge amounts of radioactive material would be scattered across the surrounding area.

However, opening the required valve to ventilate the reactor building was an extremely difficult operation. The power plant operators assembled a “suicide squad” that rushed to where the valve was located, but radiation levels were so high that they had to turn back.

Fukushima Central Television

Around 6 a.m., just outside the building, Umematsu’s crew began full-scale operations to connect the power cable. Umematsu used a phone to report on progress to the emergency response office. As reception was poor, he kept moving around looking for a place where it would be easier to talk.

Without realizing it, he ended up nearby the exhaust tower through which steam exited the vent. At exactly the same time, efforts to open the valve from the outside finally succeeded.

Steam containing huge amounts of radioactive particles instantly rushed out of the exhaust tower, thoroughly irradiating Umematsu. “When I was near the exhaust tower, the dosimeter, which had been unresponsive for a while, suddenly came back to life with a loud BEEEEP. While cursing my luck, I had no choice but to continue working,” he said.

Japanese law sets maximum exposure levels for the general public at less than 1 millisievert per year (approximately 0.0027 millisieverts per day). Umematsu, on the other hand, was exposed to over 80 millisieverts in just one day.

Just As The Cable Was Connected …

The release vent is believed to have been successfully opened around 2:30 p.m. on March 12. Immediately after, efforts to connect the power cables, which had continued throughout the night, came to a successful completion.

It was now simply a matter of turning on the movable generator to restore power. Umematsu’s crew, in order to exchange places with the group that would operate the movable generator, had to leave the area and temporarily adjourn to the emergency response office in the earthquake-proof building.

Advertisement

“I believe it’s the same in power plants everywhere. Before moving on to the next job, you must let everyone know and get permission. You can’t proceed solely on your own judgment,” he said. “I would always let machine operators know that I finished this task, that I performed that check, and so on, then I would clear things with my superior, and only then would I proceed to the next task.”

Fukushima Central Television

It all happened exactly at moment Umematsu and his crew arrived at the emergency response office.

“It wasn’t a ‘whump,’ or a ‘thud,’ it was more like a popping sound,” he said.

At 3:36 p.m. on March 12, a hydrogen explosion shook the Unit 1 reactor.

For an unknown reason, the hydrogen that had filled the reactor building suddenly caught on fire and exploded. Concrete chunks from the gutted building flew across the entire area of the nuclear reactor at tremendous speeds.

“Find an empty car!”

Umematsu was shouting at the nearby workers at the top of his lungs. Radioactive rubble and insulation material was falling from the sky. He sensed that he would be exposed to considerable amounts of radiation just by touching it.

Fukushima Central Television

A fire engine happened to be parked nearby. The workers squeezed into the front and back seats one after another. Over 10 people crammed into a space normally meant for six. They kept the door closed for about 10 minutes. Holding their breath, they waited for the pollutants to pass by.

“‘There’s no going back now. The unthinkable has happened,’ I thought to myself. At that point I felt courage sweep over me. If you are on the scene of a Chernobyl-like disaster, it makes no difference anymore whether you’re inside or outside the reactor,” Umematsu said.

Plagued By Regret After More Than A Decade

Advertisement

The hydrogen explosion shredded the power cables.

The surrounding area was once again littered with rubble. The repair work being carried out at reactors 2 and 3 had to start anew, which led to the following crisis.

The hydrogen explosion in the Unit 1 reactor could have been averted if only power could have been immediately supplied through the cable Umematsu’s crew had connected … The future could have been different. The expression on Umematsu’s face as his thoughts wandered back to those days, betrayed a deep anguish.

“Back then, if someone could have been with me at the site to issue instructions, if someone had said to me, ‘Leave things with me here and get ready to run power through the cables the instant they are connected,’ we could have done it,” he said.

Fukushima Central Television

“I immensely regret that we all went up to the office, even though the cables had been connected and we were ready to go. Looking back now, I feel we may have been too complacent,” he said.

Umematsu continued to work to connect the power supply into the following day, but from March 14, his radiation exposure had been so high that he was no longer allowed to work on-site. On the 15th, he had to evacuate the area and move outside of the nuclear power plant site.

It was then that, for the first time since the earthquake, he was finally able to talk on the phone to his eldest son.

Umematsu said: “We’re really in a dire situation, but we’re not panicking yet, so don’t worry!”

One week later, Umematsu returned to the Daiichi power plant.

Fukushima Central Television

While he was not allowed to work on-site, he could still help out by preparing food and drinks for those working on-site in a contaminated environment.

“If it hadn’t been for them, the emergency wouldn’t be over, you know.”

Advertisement

Stronger Than Fear, An Obligation To Help

At the time of the Unit 1 reactor explosion, Tochimoto, who had been working on repairing the road and removing rubble, was taking a break in the earthquake-proof building.

“‘What the hell is this!’ I thought. It came as a huge shock,” he said.

He waited for a few minutes and when he went outside, concrete and heat-insulating materials were scattered everywhere. Realizing that unless the area was again cleared of debris, vehicles wouldn’t be able to pass, he resumed working next to the reactor building.

“There was definitely radioactivity in the air, but I hadn’t been given a dosimeter so I had no way to tell,” he said.

Fukushima Central Television/Provided by: Ministry of Defense

Around him, some workers were scared of going to the work area, fearing that another explosion might follow. After all, who wouldn’t be afraid of working at a site rife with radiation as chunks of concrete rained down?

As for Tochimoto, however, another thought had begun to take hold in him. “Stronger than fear was the awareness that I had to do something about it. I felt I had to do everything in my power to help with the situation, even more so since I was a local,” he said.

Tochimoto was born and raised in Fukushima’s Futaba district, where the Daiichi power plant is located. Up until the time the nuclear power plant was built, the area was jokingly referred to as “the Fukushima boondocks,” because of how poor it was.

During the off-season for farmers, Tochimoto’s father would go look for work in big cities like Tokyo. In order to make ends meet and put food on the table, that’s what a lot of families had to do. As his father would only come home once a month, and sometimes not even then, Tochimoto says they never really had time together as a family.

After years of working hard away from home, his father learned how to operate a dump truck and eventually established the family’s heavy machinery company.

Advertisement

Fukushima Central Television

In the following years, the building of the nuclear power plant brought jobs and employment to the area, and the Tochimotos had a family life for the first time. They lived a quiet life, and the sight of his father playing with his grandchildren brought a smile to Tochimoto’s face.

“After things calmed down, my dad used to play a lot with his grandchildren. He would give them rides on his machines and play in many different ways with them. They were so cute,” he said.

The daily lives of local families, the foundation for which had been laid by his father’s generation, had prospered and continued to this day. Tochimoto recounted that while he faced extreme danger at the plant, as a local man, these memories were very strong in his mind.

To Leave Or To Go Back To The Nuclear Power Plant?

Tochimoto was once again opening a road through the rubble so vehicles could pass through. Unaware of how radioactive the scattered debris really was, he worked in close proximity to them, removing them one by one with the excavator.

At some point, the power plant’s female employees tried to evacuate from the area by minibus.

“They were already in the bus, but they couldn’t find a driver. When they asked if anybody could drive them, everyone fell quiet. Knowing that someone had to volunteer, I told them I’d do it. I felt I had to help in any way I could,” he said.

Fukushima Central Television/TEPCO

Driving the evacuation bus meant he would have to drive it back to the nuclear power plant so that more people could be evacuated again. Those being evacuated, on the other hand, would not return to the plant. He got at the wheel of the bus carrying the evacuees and headed to a junior high school outside the nuclear power plant premises. The thought of joining the evacuees himself crossed Tochimoto’s mind.

But eventually he made his way back to the nuclear power plant.

“A part of me didn’t want to go back, but there were still people working at the nuclear power plant. I headed back to the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant while thinking all the time I really should be heading home,” he said.

Advertisement

A ‘Local Guy’ Fighting Alongside Special Forces

After returning to the nuclear power plant, Tochimoto, in addition to removing rubble, also took part in efforts to secure water to cool the reactor. They would go around the site in search of water accumulated in the facilities and transport it to the fire engine.

The system for directly cooling down the reactor was out of order at the time. They were therefore trying to cool it by connecting the fire hoses to pipes that would directly inject water into the reactor.

Fukushima Central Television/Ministry of Defense

On March 14, the Ground Self-Defense Forces arrived at the site where Tochimoto was working. It was the Central Nuclear Biological Chemical Weapon Defense Unit, which was qualified to deal with chemical weapons, including radioactive materials.

After filling the water truck of the Self-Defense Forces with water from the pressure filter tank near the reactor building, six people, including Colonel Shinji Iwakuma, who led the unit, headed to the Unit 3 Reactor. Tochimoto and his crew were also busy pouring water from the same tank into a sprinkler truck.

“I heard a ‘BOOM!’ I looked up and I saw what resembled a mushroom cloud,” he said.

At 11:01 a.m. on March 14, a hydrogen explosion occurred in the Unit 3 reactor.

Once again, countless chunks of concrete fell down from the sky. The members of the Self-Defense Forces were directly below. Four out of six were seriously injured. One of them was bleeding and had to be urgently transported to a specialized medical center by helicopter due to the risk of internal radiation exposure. Tochimoto immediately jumped into a car and left the scene.

Fukushima Central Television/TEPCO

Tochimoto’s crew, in spite of witnessing two hydrogen explosions, resumed their work of removing the scattered rubble shortly after.

“I was told they were having problems at the power plant, so I was asked to help out. I couldn’t just say no. I thought I had no choice but work together with them. We had to assume we could turn things around,” he said.

Advertisement

Radiation levels within the nuclear power plant suddenly soared, and on the night of the 14th, Tochimoto too was finally ordered to evacuate. “Take it from here,” he said to the power plant staff, handing them the excavator’s key.

In spite of never having been closely associated with the nuclear power plant, he fought at the risk of his life until the very the last minute.

Like Umematsu, Tochimoto would later return to the Daiichi power plant. During the two weeks he was away, he learned how to remotely operate a concrete pump for injecting water into the reactor’s spent fuel pool and remained at the forefront of the efforts to resolve the emergency.

Eleven Years Later, ‘One Step At A Time, I Think Progress Is Being Made’

Following the successive meltdowns and hydrogen explosions, during a brief period of comparative calm, a system for cooling the reactor and the nuclear power plant began to be put in place. While Umematsu and Tochimoto were away, the Self-Defense Forces, the National Police Agency, the Tokyo Fire Department and the power plant’s own response team entered the site and began to work to restore power.

Thanks to them, it was finally possible to bring the overheating nuclear power plant to a halt at the last minute.

The worst-case scenario envisioned by the Japanese government, in which half of Japan would be destroyed and Tokyo itself would become uninhabitable, was thus averted by efforts on all sides.

The power plan at the center of this disaster continues to pose great risks. The nuclear fuel debris resulting from the meltdowns remains underground inside the plant. It is estimated to total about 880 tons and it continues to emit lethal doses of radiation, making it impossible for workers to approach it.

The Japanese government has joined forces with the power plant and Japanese companies like Toshiba, Hitachi and many others to tackle the removal of the debris, a difficult project and the world’s first of this kind. The only way to remove the debris is by remotely operated robots.

Eleven years after the accident, veteran engineer Umematsu returned to the site for an inspection.

Advertisement

He wanted to see once again the scene of the nuclear accident that had shattered Japan’s pride in the technological capabilities that had supported its postwar reconstruction, and which may still yield the opportunity for regaining that pride.

Robots small enough to navigate even the narrowest spaces inside this highly radioactive area were removing the rubble from inside the nuclear power plant piece by piece, while sending back images. All the workers operating the robots were young and are allowed to work only after months of training and simulations.

“Even a single piece of rubble is highly radioactive and dangerous. Even the smallest mistake can cause a huge accident, so we cannot afford to make any mistakes,” an engineer said.

Umematsu stared in silence at the young engineer who had said these words. And standing, for the first time since that day, at the site where he had supervised efforts to restore power, he said: “I really think we gave our very best at that time, and yet we didn’t succeed. Power was not restored. But I don’t think it was all in vain.”

“Oftentimes you must suffer multiple failures in order to attain a single result,” he added. “That’s how you move forward. From the perspective of removing the nuclear debris, I think advances are almost insignificant. And yet, one step at a time, I think progress is being made.”

Even though 11 years have passed since the accident, the removal of fuel debris has yet to start. Nonetheless, Umematsu thinks that “nothing is ever in vain.” And the simple fact that he can say these words is proof that the biggest problems have been overcome.

Related posts:

Views: 0

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

March 12th, 2022

March 12th, 2022  Awake Goy

Awake Goy  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: