When it comes to ancient Egypt and its long lasting and influential civilization, plenty of its unique characteristics can seem peculiar and otherworldly. Sure, it is no secret that ancient Egypt was home to some odd beliefs and quirky traditions. But to them, all of it held deep meaning and religious significance. One of the oldest and strangest of these traditions is certainly the mummification process. Embalming the dead in order to provide artificial mummification is not a novelty in human history, but the mummification process was certainly perfected in ancient Egypt where this practice survived for thousands of years. But how did they do it? And most importantly, why?

The Origins and Nature of the Mummification Process

Over the years, the classic depiction of a linen-wrapped mummy became an iconic symbol of the ancient Egyptians. But the actual word “ mummy” has nothing to do with it! There is quite a rocky history to that simple word. The English version was borrowed from the Latin word mumia. This in turn was borrowed from Arabic in the middle ages, from the word mūmiya ( مومياء), which stems from the Persian word mūm, meaning “wax.”

This term was meant to signify an embalmed corpse and eventually found its way into English, where by the 1600s the word was used for naturally preserved desiccated human bodies. As such the modern day word mummy does not refer exclusively to those mummified bodies of ancient Egypt. “Mummy” can refer to any type of ancient and modern mummified body that was preserved either through natural processes or artificial ones. But, of course, not all mummies are so captivating and enigmatic as the ones found in ancient Egypt.

The Gebelein predynastic mummies were preserved through a natural mummification process thanks to the conditions in the desert. They provide a window into understanding the development of the mummification through time. The image shows the reconstructed sand grave of one of the males at the British Museum. (InSapphoWeTrust / CC BY-SA 2.0 )

The Gebelein Predynastic Mummies

Perhaps the oldest discovered mummies of ancient Egypt are known as the Gebelein predynastic mummies. These six bodies were naturally mummified, thanks to the arid landscapes they were found in. The hot sands and dry air helped to keep these bodies relatively well preserved, keeping in mind that they are dated to roughly Gebelein 3400 BC!

is located on the River Nile , some 40 kilometers south of Thebes, a crucial Egyptian city. Found in shallow graves with sparse grave goods, these six mummies come from the earliest stages of the ancient Egyptian civilization, the so-called predynastic period. As such they provide an important glimpse into the development of their funerary customs and the development of mummification as well.

This is due to the fact that three of these bodies were covered with different materials: reed mats, animal skins, and palm fibers. This was perhaps an early attempt to help with the mummification processes. While most bodies of the predynastic era were buried naked, some were wrapped or covered with such fabrics, which could have gradually evolved into a more complex form of embalming and mummification.

Death and the Afterlife for the Ancient Egyptians

As a civilization evolves, so do the most important of its aspects. And, of course, death can be as important for a civilization as life itself. For the ancient Egyptians, death and the afterlife were one of the cornerstones of all their beliefs. As time progressed so did these funerary rites, until the time they became established with a series of patterns and traditions that continued on for a long time after.

Mummification – the preservation of the body – became an important aspect in these traditions. The Egyptians believed that if one was to secure his position in the afterlife, the dead body needed to be preserved. This was instrumental in their belief in ka, the concept of the soul. Upon death, the ka leaves the body, but can return to it only if it is preserved. Thus a preserved body can go in front of Osiris in the afterlife, where it is rejoined with its soul, where the person then lives in joy in the afterworld. But if a body is not preserved, this important cycle of rebirth cannot be completed.

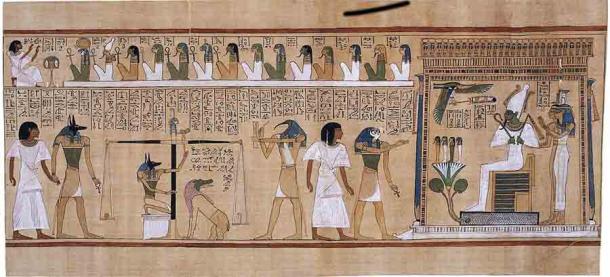

In order to reach the afterlife, the dead body needed to be preserved. During judgment their heart would be weighed and compared against a feather of Maat, and the righteous would be welcomed into Aaru, the heavenly paradise ruled by Osiris, the god of the afterlife. ( Public domain )

For Flesh To Rejoin With the Soul: The Mummification Process

The Egyptians gradually perfected their mastery of the mummification process. One of the key components to help them with this was natron, a kind of natural salt found in Wadi Natrun, a very important valley in northern Egypt, considered sacred to them. Natron is composed of sodium carbonate decahydrate and sodium bicarbonate, along with small amounts of sodium chloride and sodium sulfate. This unique combination of elements makes it a great natural drying agent, which was recognized to help with the mummification process as it quickly dehydrates the body – a key aspect of preserving the body through time.

The process of embalming and mummification was lengthy and complex – and not at all attractive. The treatment of the deceased person usually began with the removal of the brain. Its removal remains one of the more puzzling aspects of the mummification, but scholars usually agree that this was done either by a special hook which was inserted through the nose and into the brain cavity, or with a special rod inserted into the cranium that liquefied the brain matter.

Either way, the liquefied brain was poured out through the nose of the deceased and the process could proceed to the next level. No importance was given to the brain. The ancient Egyptians believed that it was the heart of a person that was responsible for all the thinking. The previously emptied brain cavity was then filled with a special mixture of fragrances and tree resin. This mixture served to minimize the natural putrid smells of decomposition, but also to halt the decomposition process of any residual brain matter that remained in the skull.

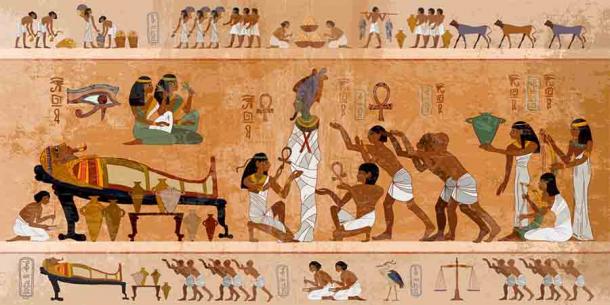

While the funerary rites and customs of ancient Egypt can seem bizarre to some, the intricate mummification process was part of the complex vision of the ancient Egyptians as relating to death and the afterlife. ( Matrioshka / Adobe Stock)

The process then moved towards the abdominal area of the deceased. It was cut open and the main organs removed, covered in salt or natron, and carefully placed in special canopic jars, to be buried alongside the mummified body. The heart was not removed in this process most of the time. Thus the emptied abdomen was filled with a fragrant mixture of aromatics that again helped with the foul smells of death.

After this was finished, the “prepared” body was rubbed with natron and covered with it entirely. It then lay in natron for a period that ranged between 30 and 70 days, until the process of dehydration was complete. The body could then be embalmed and mummified. The body was washed, covered with fragrant oils, and then covered with resin, often with several layers of it. The resin acted as a natural adhesive for the layers of linen that were then used to wrap up the entire body – strip by strip. In the end, the body could have been adorned with funerary masks, but this was mostly reserved for high class individuals.

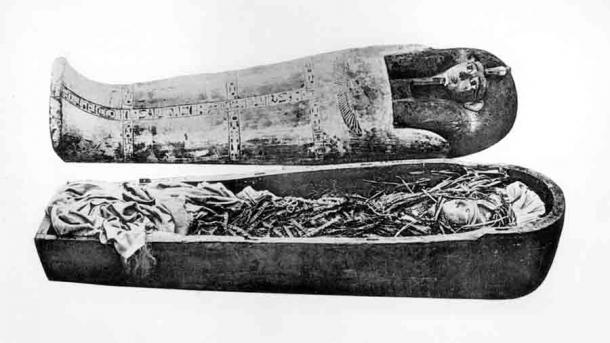

The mummification process of bodies of people from different social classes differed. Those from the upper class or nobility was complex and time consuming, such as that used for the mummified body of Amenhotep I, housed at the Egyptian Museum in Cairo. ( Public domain )

Deluxe Treatment for the Deceased

This mummification process was separated into three classes: a high-end, detailed embalming process for the upper class and nobility, as detailed above; a mid-range process; and a lower class process for the poorest citizens. Likewise, the embalming process was most likely done by different castes of officials: the high-end mummification was done by priests of importance and noble background, while the lowest class process was possibly done by initiates and the lowest class in Egyptian priesthood.

Depending on the class you could afford, the body could be treated accordingly. Some poor families chose to allow the process of decomposition to begin before giving the body away to the embalmers. If they did not do so, the bodies of recently deceased young women would be desecrated through necrophilia.

The processes differed too depending on social status. For the mid-range embalming process, there were fewer steps. The abdominal cavity was not opened: instead it was filled with cedar oil which liquefied them and they were simply poured out. After the dehydration was done, the body was given over to the family. The lowest class of embalming was even more rugged and very crude. Besides the ever-present possibility of necrophilia, the body was simply and quickly devoid of all internal organs, laid in natron for a certain number of days, and once completely desiccated, it was returned to the family in that way for burial.

This detailed information regarding mummification process provides important insight into the social divisions that existed in ancient Egypt. Although separated into classes, the mummification process was generally available to every citizen, rich or poor. This was due to the important beliefs centered on death.

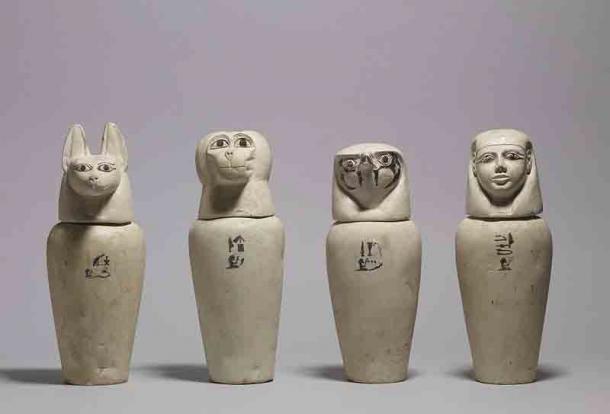

Canopic jars were used to store the internal organs of the deceased which were needed in the afterlife. Each represented a different deity with the head of a jackal, an ape, a hawk and a human. ( Public domain )

Deity Guards of the Internal Organs

The processes described above allow experts to deduce that internal organs were believed to be of particular importance. Why were they placed in special canopic jars? These jars usually numbered four, and represented the four guardians of the internal organs. A key part of the body, they too needed to be preserved for the afterlife. They were thus guarded by the four Sons of Horus, major protective deities responsible exclusively for this role – guarding the internal organs.

These deities were Hapy, Duamutef, Imsety, and Qebhseneuf – and each one had his role. Hapy was the ape-headed god who guarded the lungs of the deceased. The stomach was guarded by Duamutef, the jackal-headed god. Qebhseneuf was hawk-headed and protected the small and large intestines. Finally, Imsety, the human-headed god, guarded the liver. The heart was not removed: it stayed inside the body to be weighed on the scales of the Goddess Maat, against a feather in the Hall of Judgment.

The Mummified Body of Pharaoh Tutankhamun

This elaborate embalming process, and the intricate beliefs associating it, are best observed in the burials of high-class persons, pharaohs, and nobles. An iconic example is the burial of Tutankhamun, the famed pharaoh of the 18th dynasty. Even though the mummy is roughly 3,300 years old, it nevertheless showcases the process in stunning detail.

The king was lavishly prepared for his journey into the afterlife. His mummified body was protected by three special coffins, nested into one another, and then housed into a sarcophagus and further four nested chambers. But the actual mummified body was of particular interest to researchers as it provided important understanding of the mummification process itself.

The body of the pharaoh was wrapped in numerous linen layers, and excessively covered with special oils. Every successive layer of wrappings contained precious items that would serve the pharaoh in his afterlife. Together with his rich burial goods, the mummy of Tutankhamun remains one of the most important discoveries in Egypt.

The tomb of Tutankhamen was discovered by archaeologist Howard Carter in 1922. The mummy of the famed pharaoh provided a wealth of information about the mummification process. ( Public domain )

Preserved for all Eternity

It is important to remember that the ancient Egyptians did not only mummify their deceased citizens. Animals went through the same processes – and in great numbers too. While there are possibilities that some animals were mummified as household pets to accompany their owners, most others were mummified as sacrifices to the gods.

Since a vast majority of Egyptian deities had animal aspects, respective animals were used to honor them and gain their favor. Archeologists have discovered entire cemeteries filled with nothing but various animal mummies: hawks, crocodiles, ibises, cats, baboons, fish, mongoose, jackals, dogs, beetles, serpents, and many others. These animals were offered in great numbers. It is estimated that in the Saqqara burial fields alone there are over 500,000 mummified ibises . Entire fields of mummified cats were likewise discovered.

However we choose to look at this process, to the modern mindset it could appear grizzly and repulsive, to the ancient Egyptians the mummification process was fundamental and sacred. Such an elaborate preservation of dead bodies was a sure sign that the soul would reach the afterlife. One can also assume that their view of death was much more natural.

Overall, the process of mummification and embalming differed greatly from other neighboring funerary practices of the time. The ancient Greeks and later the Romans, did not have such practices. And, perhaps, most importantly, the process tells us just how advanced the ancient Egyptian civilization was in every aspect. To give so much care to preserving a dead body and to develop such innovative ways to do it is a telltale sign of the unique character of ancient Egypt.

Top image: The mummification process evolved over the centuries. Here an example from the Louvre collection, France. Source: Netfalls / Adobe Stock

By Aleksa Vučković

References

Aufderheide, A. 2003. The Scientific Study of Mummies. Cambridge University Press.

Bloxam, E. and Shaw, I. 2020. The Oxford Handbook of Egyptology. Oxford University Press.

Garlinghouse, T. 2020. Mummification: The Lost Art of Embalming the Dead. Live Science. Available at: https://www.livescience.com/mummification.html

Related posts:

Views: 0

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

March 9th, 2021

March 9th, 2021  Awake Goy

Awake Goy  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: