The Argead dynasty was a royal dynasty that founded and initially ruled over the Kingdom of Macedon. This dynasty traces its origins all the way back to the mythical hero Heracles, via Temenus, his great-great-grandson. The dynasty’s association with Temenus also means that the Argeads could claim that their ancestral homeland was the Peloponnese. The Argeads migrated from this part of the Greek world to the north and founded the Kingdom of Macedon.

For much of its history, Macedon was a minor kingdom on the edge of the Greek world. The kingdom rose to prominence, however, during the 4 th century, under the leadership of Philip II, and his son, Alexander the Great. During the latter’s reign, an empire was created, but it disintegrated as soon as Alexander died. The Kingdom of Macedon survived till the 2nd century BC, though the Argead dynasty had gone extinct by the end of the 4 th century BC.

A painting of Hercales, whose great grandson Temenus was the founding father of the Argead dynasty, choosing between Pleasure on the right and Virtue on the left. (Annibale Carracci / Public domain )

The Founding Histories and Myths of the Argead Dynasty

The Argeads claim to be the descendants of Temenus, a great-great-grandson of Heracles, and King of Argos. The ancient historian Herodotus provides an account of how the Argeads came to rule over Macedon. According to Herodotus, three Temenid brothers, Gauanes, Aeropus, and Perdiccas, were banished from Argos to Illyria.

They wandered in the highlands of Macedon, and finally settled down in a town called Lebaea. There, they worked for the king, tending to his livestock. The queen, who prepared the food for the king’s workers, noticed that whenever she baked bread, Perdiccas’ would double in size. She reported this anomaly to her husband, who regarded it as an ominous sign.

Therefore, the king summoned the three brothers, and told them to leave his kingdom. Before leaving, however, the brothers asked the king to give them their wages. Instead of paying them, the king pointed to the ray of light that shone down the smoke vent into the house and told the three brothers that that was all they deserved, and all that he would pay them. Whilst Gauanes and Aeropus were left speechless, Perdiccas accepted the king’s ‘wages’ and drew a line on the floor around the sunlight with a knife. He gathered the sunlight in the folds of his garment thrice and departed with his brothers.

After the brothers had left, the king decided to send men to kill them. One of the king’s attendants had told him the meaning of Perdiccas’ actions, which angered him. The king’s men, however, failed in their mission, as they were blocked by a river. After the brothers had crossed the river, it flooded, thus preventing their pursuers from crossing it. Herodotus notes that as the river had delivered them from their enemies, the Argeads offered sacrifices to it from then on.

In any event, Perdiccas and his brothers arrived in another part of Macedon and settled close to a site called the “Garden of Midas.” Perdiccas is recognized as the founder of the Argead dynasty, and the Kingdom of Macedon.

Thucydides, the author of the History of the Peloponnesian War , offers a slightly different account from Herodotus about the founding of Macedon. Like Herodotus, Thucydides records that the Argeads were originally Temenids from Argos. Instead of focusing on signs and omens as Herodotus did, Thucydides reports that the Argeads established their kingdom through conquest and expelled the native inhabitants from the territories they seized. These included the Pierians, Edoni, Eordians, and Almopians.

Macedonian coins from the reign of the earliest kings of the Argead dynasty between 510 and 480 BC. (Classical Numismatic Group, Inc. http://www.cngcoins.com / CC BY-SA 3.0 )

The Other Argead Dynasty Origin Version is Quite Different

It should be mentioned that there is an alternate myth regarding the founding of Macedon. This story, however, is found in sources that were written long after Herodotus and Thucydides.

According to this myth, the kingdom was not established by Perdiccas, but by Caranus, a legendary king who lived before him. Like the other version of the myth, Caranus is also a Temenid. Therefore, in either account, the Argeads are portrayed as the descendants of Temenus.

Unlike Perdiccas and his brothers, Caranus was not exiled from Argos. Instead, he went to the north, along with a group of followers, to aid the king of the Orestae, who was at war with a neighboring tribe, the Eordaei. In return for his aid, the king promises to give Caranus half his territory. Thanks to Caranus’ help, the Eordaei are defeated. The king keeps his promise, and hands over half his territory to Caranus. This marks the beginning of the Kingdom of Macedon. According to this version of the story, Perdiccas is separated from Caranus by three or four generations.

According to Herodotus, from the establishment of kingdom till the time he was writing his Histories, i.e., around 430 BC, Macedon had been ruled by seven kings. Herodotus names all seven kings, and, from the first to the last, are as follows: Perdiccas, Argaeus, Philip, Aeropus, Alcetes, Amyntas, and Alexander. During the reign of these Argead kings, Macedon was a minor kingdom on the fringes of the Greek world, and, for the most part, was not involved in Greek politics . In fact, up till the end of the 7 th century, the Macedonians were busy fighting against the Illyrians and the Thracian tribes, who threatened to destroy the kingdom.

During the reigns of Amyntas and Alexander, Macedon became a vassal state of the Achaemenid Empire . It was during Alexander’s reign that the Achaemenids invaded Greece, first under Darius I, and then under Xerxes I. Although the Macedonians were vassals of the Achaemenids, they were also helping the Greeks, by sending them supplies, and information about the movements of the Achaemenid forces.

When the second Achaemenid invasion was repelled, Alexander seized the opportunity to free his kingdom from the Achaemenids. As the Achaemenid survivors of the Battle of Plataea were retreating to Asia Minor by land, they passed through Macedon, and many were killed by the Macedonians.

Having regained Macedon’s freedom from the Achaemenids, Alexander began to expand his kingdom by conquering the neighboring tribes that were independent of Macedon’s rule. Alexander’s successes, however, were not sustained by his immediate successors.

His son, Alcetas II, for instance, was an alcoholic, and was murdered by his nephew, Archelaus. The next king, Perdiccas II, succeeded his murdered brother, but his claim to the throne was contested by Philip, another of his brothers, and Amyntas, Philip’s son.

As a consequent of the internal troubles faced by the Argeads, the newly conquered tribes started to exert more autonomy. For instance, Perdiccas was involved in a war with the Lyncestae tribe and their Illyrian allies in 424-423 BC. He was defeated by them and forced to retreat.

The death of Alexander II, Amyntas’ son and successor. ( Public domain )

Fortifying Macedon During the Sparta-Athens Wars

In spite of these troubles at home, the Macedonians were involved in the Peloponnesian War , which pitted Athens against Sparta, and lasted from 431 to 404 BC. The king, Perdiccas, was a fickle ally, shifting his alliance between Athens and Sparta multiple times as the war progressed. Perdiccas’ successor, Archelaus I, who reigned from 413-399 BC, eventually stabilized relations with Athens, by supplying it with timber. This resource was needed by the Athenians, as their fleet was destroyed following the disastrous expedition against Syracuse.

Archelaus also built strongholds and roads throughout the kingdom, thereby stabilizing its organization and infrastructure. Unfortunately for Archelaus, he was killed, possibly an accident, by Craterus, one of his royal pages, during a hunt.

Although Archelaus succeeded in strengthening Macedon, his achievements were largely undone by his successors, and the fortunes of the kingdom fluctuated during the first half of the 4 th century BC.

The last years of the first decade of the century were a chaotic time for Macedon. In one year, 393 BC, for example, the Macedonian throne was occupied by four kings – Amyntas II, Pausanias, Amyntas III, and Argaeus II. There is little information about these kings.

Nevertheless, we do know that Pausanias was assassinated by his successor, Amyntas III, who in turn was driven out by the Illyrians. These tribesmen were assisting a pretender, Argaeus II, to seize the Macedonian throne. The actions and fates of these Macedonian kings suggest that the situation of the kingdom at that time was quite unstable.

This chaotic period was followed by a revival in Macedon’s fortunes. In 392 BC, Amyntas was restored to his throne, and ruled Macedon until 370 BC, when he died of old age. In the early years of his reign, Amyntas succeeded in creating a unified kingdom, and improved relations with the Odrysian Kingdom, a powerful Thracian kingdom to Macedon’s northeast.

In the decade following Amyntas’ death, however, the kingdom plunged into chaos once more. Amyntas’ son and successor, Alexander II, for instance, reigned for two years before he was assassinated by Ptolemy I. Alexander’s brother, Perdiccas III, became the next king, but was forced to accept Ptolemy, his brother-in-law, as his regent. The regent was eventually killed by the king, who himself lost his life several years later during a battle with the Dardani, an Illyrian tribe.

Alexander the Great or Alexander III led the Argead dynasty to its highest point of power and influence. ( gianmarchetti/ Adobe Stock)

From Philip II To Alexander the Great

Perdiccas was succeeded by his infant son, Amyntas IV. The new king’s uncle was appointed as his guardian, but would ultimately seize the throne for himself, and rule Macedon as Philip II.

One of the first challenges to Philip’s reign came in the form of Argaeus, who may have been the same pretender who seized the throne back in 393 BC. This Argaeus hoped to rule Macedon once again and tried to obtain aid from the Athenians. Philip succeeds in neutralizing this threat by persuading the Athenians not to interfere. The lack of Athenian support, however, does not stop Argaeus from launching an attack on the Macedonian capital. The attack was repulsed, and the pretender was forced to retreat. In the ensuing ambush by Philip, Argaeus was either killed in battle, or captured and executed.

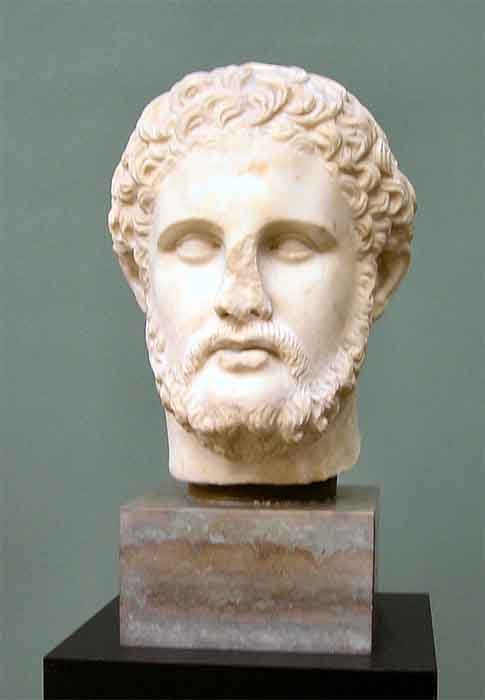

A Roman copy of a Greek original of King Phillip II of Macedonia. (Richard Mortel from Riyadh, Saudi Arabia / CC BY 2.0 )

Like his predecessors, Philip II also had to deal with the hostile Illyrian tribes that bordered the kingdom. Philip resorted not only to force of arms, but to other means as well, when dealing with this threat.

The recruitment and training of a new Macedonian army in 359 BC enabled Philip to crush the Dardani tribe in the following year. Around the same time, Philip married Olympias, a Molossian princess who was the niece of King Arybbas I of Epirus. This marriage cemented the alliance between Macedon and Epirus, enabled the two kingdoms to focus their resources on a common enemy, i.e., the Illyrians. In this way, Philip II secured his kingdom’s western borders.

Philip then turned his attention to the eastern borders of his kingdom and captured the strategically important settlement of Amphipolis. This alarmed the Athenians greatly, as this threatened their own position as a naval power. The capture of Amphipolis gave Philip control over gold mines, forests that supplied timber of the building of ships, and the road into Thrace. In any case, the Athenians and their allies were powerless to oppose Macedon’s ascent. In time, Philip’s ambitions were seen as a threat not only by the Athenians, but by the rest of Greece as well.

In 338 BC, Philip defeated the Greeks who were led by Athens and Thebes at the Battle of Chaeronea. This was a decisive victory of Philip, as Greek opposition was crushed once and for all, and most of Greece, with the exception of Sparta, came under Macedonian hegemony. A year later, Philip established the League of Corinth, with himself as its hegemon, or leader. Using the League, Philip presented himself as the head of a grand, pan-Hellenic army that would march against Greece’s greatest enemy, the Achaemenid Empire.

Head of Alexander the Great, by Leochares, from about 330 BC. (Acropolis Museum / Public domain )

In 336 BC, however, Philip II was assassinated by one of his bodyguards, Pausanias. The king’s dream of conquering the Achaemenids, however, did not die with him, but was taken up by his successor, Alexander III, more commonly known as Alexander the Great.

By the time of Alexander’s death in 323 BC, the Macedonians were in control of an empire that stretched as far east as the Indus River. This empire, however, was short-lived, as it was divided amongst Alexander’s generals shortly after he died.

After Alexander’s death, the Argead dynasty continued its existence for another 13 years. The last two Argead rulers of Macedon were Philip III Arrhidaeus, and Alexander IV.

Philip was Alexander the Great’s mentally disabled elder half-brother and was served as a titular king. In 317, Philip was captured by the forces of Olympias when they invaded Macedon and executed.

Alexander IV, on the other hand, was the son of Alexander the Great and Roxana. He too served as a titular king, as he was a minor. In 310/09 BC, when Alexander IV was only 13/14 years old, he was assassinated by Cassander, in order to prevent him from ascending to the Macedonian throne.

The death of Alexander marks the end of the Argead dynasty, though the Kingdom of Macedon continued to exist until the 2 nd century BC.

Top image: The Argead dynasty and the founding of the Kingdom of Macedonia reached its highpoint under the leadership of Alexander the Great. Photo source: Lambros Kazan / Adobe Stock

By Wu Mingren

References

Biography.com Editors, 2020. Philip II of Macedon Biography. [Online]

Available at: https://www.biography.com/political-figure/philip-ii-of-macedon

Griffith, G. T., 2020. Philip II. [Online]

Available at: https://www.britannica.com/biography/Philip-II-king-of-Macedonia

Herodotus, The Histories

[Waterfield, R. (trans.), 1998. Herodotus’ The Histories . Oxford: Oxford University Press.]

History.com Editors, 2018. Macedonia. [Online]

Available at: https://www.history.com/topics/ancient-rome/macedonia

Kessler Associates, 2021. Macedonia / Macedon. [Online]

Available at: https://www.historyfiles.co.uk/KingListsEurope/GreeceMacedonia.htm

Lendering, J., 2019. Philip II of Macedonia. [Online]

Available at: https://www.livius.org/articles/person/philip-ii-of-macedonia/

Lendering, J., 2020. Argeads. [Online]

Available at: https://www.livius.org/articles/dynasty/argeads/

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica, 1998. Argead Dynasty. [Online]

Available at: https://www.britannica.com/topic/Argead-dynasty

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica, 2021. Macedonia. [Online]

Available at: https://www.britannica.com/place/Macedonia-ancient-kingdom-Europe

Thucydides, The Peloponnesian War

[Hammond, M. (trans.), 2009. Thucydides’ The Peloponnesian War . Oxford: Oxford University Press.]

Related posts:

Views: 0

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

April 6th, 2021

April 6th, 2021  Awake Goy

Awake Goy  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: