Recently, a farmer ploughing his field in Egypt’s Ismailia Governorate dug up something massive and historically significant. The unnamed farmer was shocked to realize the heavy object he’d uncovered was not a large rock. It was actually a huge stone Egyptian stele that contained hieroglyphic writing in an ancient language.

Suspecting he’d found something important the man immediately contacted the local Tourism and Antiquities Police. After retrieving it, antiquities experts identified the thick stone slab as an ancient Egyptian stele , or sandstone monument. This stele was constructed in the sixth century BC, as a monument to a largely forgotten pharaoh.

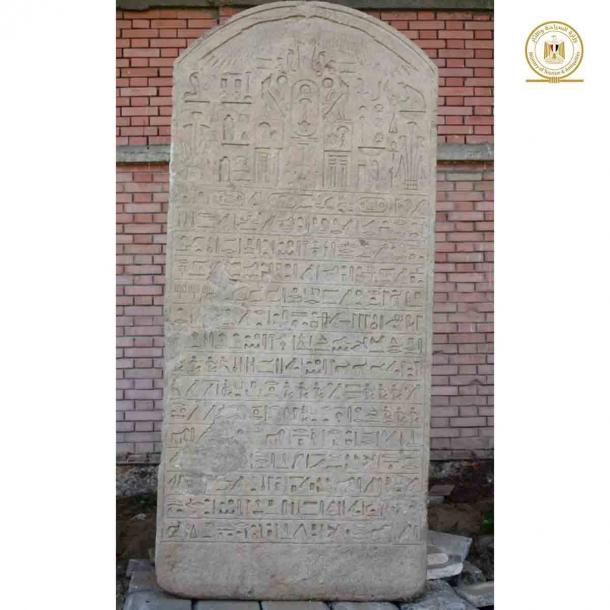

The Egyptian stele of Apries, as it was found in the farmer’s field, with its hieroglyphic inscription related to one of the pharaoh’s numerous completed or planned military campaigns . ( Egyptian Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities )

The Significance of the Egyptian Stele of Apries

The Egyptian Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities has confirmed the Ismailia Egyptian stele , found in the farmer’s field, was hammered in stone in honor of the Egyptian pharaoh Apries . Apries served as the leader of a united and independent Egypt during the 26th dynasty , holding the throne from 589 to 570 BC.

Archaeologists were able to identify the Egyptian stele as a monument to Apries because the pharaoh’s cartouche, or official royal insignia , was carved into the slab at the top. The creator of the monument also decorated it with a winged image of a sun disk, which likely represented the Egyptian sun god Ra .

The latter design choice is consistent with at least one other discovery. Archaeologists previously found a rectangular plaque associated with Apries in the ruins of an ancient temple site project in the city of Abydos, 300 miles (500 kilometers) south of Cairo. That plaque carried an inscription that referred to him as “the son of Re (Ra).” And in fact, Apries real given name was Wah-ib-re, which meant “Constant is the heart of Re (Ra).” His throne name was Haa-ib-re, which meant “Jubilant is the Heart of Re (Ra) Forever.”

The buried stele is impressive in size. It is 91 inches (230 centimeters) tall, 41 inches (103 centimeters) wide, and 18 inches (45 centimeters) thick. The farmer discovered it in a field located approximately 62 miles (100 kilometers) northeast of the capital city of Cairo , near the town of Ismailia.

The stele was exceptionally well-preserved. The 15 lines of writing it contained could still be read, and work has already begun to translate the inscription. The current working theory is that Apries ordered the stele built to commemorate a military campaign that he’d either planned or recently completed.

This is not the first stele dedicated to Apries found in Ismailia. In 2011, the Egyptian military found two sandstone slabs buried in the governate’s Tal Defna area , both of which contained hieroglyphic messages and Apries’ distinctive cartouches.

The Egyptian stele from the farmer’s field showing the cartouche of the pharaoh at the top in the middle, just below the winged sun disk image at the very top . ( Egyptian Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities )

Who Was Pharaoh Apries?

Wah-ib-re, or Apries, ascended to the throne following the death of his father, the 26th dynasty ruler Psamtik II. His service during his 19 years of rule was considered unremarkable and was ultimately destined to end in disaster.

Apries’ style of rule was aggressive and militaristic. He was frequently at war with his neighbors in Greece, Palestine, Phoenicia, Cyprus, and Babylonia, as the various powers and peoples in the region struggled for territorial control or freedom from colonization. He initiated the typical ancient Egyptian building projects, adding to temple complexes in many places. Like other pharaohs, he also ordered the construction of stele that celebrated his achievements (real or imagined).

Seeking glory through military success, Apries made a controversial decision. He supplemented his Egyptian army with a significant population of Greek mercenaries , offering them privileged positions and likely higher pay. This greatly upset the rank-and-file Egyptian native soldiers, who still comprised the bulk of his forces.

Near the end of his reign, Apries committed what turned out to be his greatest blunder. He dispatched his troops to Libya to help repel an invasion by Dorian Greeks from the city of Cyrene, which the Greeks had established as an outpost on Libyan soil. Apries’ forces were decisively defeated during this disastrous adventure, which provoked a massive revolt in the Egyptian army. The subsequent fighting pitted Egyptian natives against Apries’ hated Greek mercenaries, whose presence had likely made civil war inevitable.

Apries sent his most capable general, Amasis, to put down the revolt and stop the civil war from spreading. But to the pharaoh’s shock and horror, the Egyptians successfully recruited Amasis to become their new leader and convinced him to accept the title of the new pharaoh of Egypt.

A rare “portrait in stone” of pharaoh Apries in the Louvre Museum, Paris France. (Louvre Museum / CC BY-SA 3.0 )

Refusing to concede his throne, Apries launched two military campaigns against Amasis and his legions in 570 BC. However, both were unsuccessful. After his second failed attempt to retake power, Apries fled to Babylonia, to seek refuge in the court of Nebuchadnezzar.

Apries tried once again to regain his throne, in 567 BC. This time he was accompanied by a new mercenary force, comprised entirely of Babylonians.

Not surprisingly, Apries was easily defeated by the unified Egyptian forces. This time he was not allowed to escape, but instead was placed under arrest and finally executed by Amasis. Despite their intense rivalry, his successor did give Apries a proper burial, in recognition of his one-time status as the legitimate pharaoh of Egypt.

What is known about Apries, and his exploits, mostly comes from the fifth century BC Greek historian Herodotus, who wrote about past events in Egypt and elsewhere in the ancient world. It was Herodotus who called the multi-named pharaoh Apries, and that name is the one he is best known by today. Apries was also mentioned in a few places in the Bible, where he was referred to as the Pharaoh Hophra.

Archaeologists have discovered only a few artifacts that can be linked directly to Apries, which is one reason why Egypt’s Ministry of Antiquities was quite pleased to receive this newly excavated stele.

In 1909, archaeologists from the British School of Archaeology did find and dig out Apries’ magnificent 80,000-square-foot (24,000-square-meter) palace at the ancient site of Memphis , which once functioned as Egypt’s capital. Apries fled to Memphis after his first defeat at the hands of Amasis, in what was to be the pharaoh’s last visit to his lavishly designed and decorated showplace before his exile and eventual death.

This curious monument in Rome, the so-called Pulcino della Minerva, is a statue designed by the Baroque sculptor Gian Lorenzo Bernini of an elephant as the supporting base for an Egyptian obelisk found within Emperor Dominican’s garden. This obelisk was first constructed under the 589-570 BC reign of pharaoh Apries. (Judge Leverich / CC BY 2.0 )

Acknowledging Apries’ Greatest Legacy

Once the hieroglyphics on the newly discovered Egyptian stele have been translated, the experts will know for sure which military campaign it was intended to document.

If it in some way relates to Apries’ struggles with Amasis, it would be especially significant. These were the most momentous campaigns of the pharaoh’s relatively brief 19-year reign. They were important not because of how they relate to Apries, but because they led to the Amasis’ ascension to the throne.

While Apries didn’t accomplish anything remarkable, his successor did. Amasis, who served as Egypt’s ruler for 44 years under the title Ahmose II, was Egypt’s last great pharaoh . Under his wise leadership Egypt became prosperous and successful, in part because of the close contacts he established with the Greeks.

The reign of the man who began as Apries’ most trusted general brought back memories of past glories. It provided Egypt with one last great moment under the sun, before Persian conquerors arrived and overthrew the 26th Dynasty shortly after Amasis’ death.

Top image: The Sphinx of Apries, dated to between 589 and 570 BC. Like the Egyptian stele found in the farmer’s field, this sphinx is dedicated to the pharaoh Apries of the 26th dynasty of Egypt. Inset, stele of Apries in situ at find site. Source: Louvre Museum / CC BY-SA 2.0 FR (Inset: Egyptian Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities )

By Nathan Falde

Related posts:

Views: 0

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

June 22nd, 2021

June 22nd, 2021  Awake Goy

Awake Goy  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: