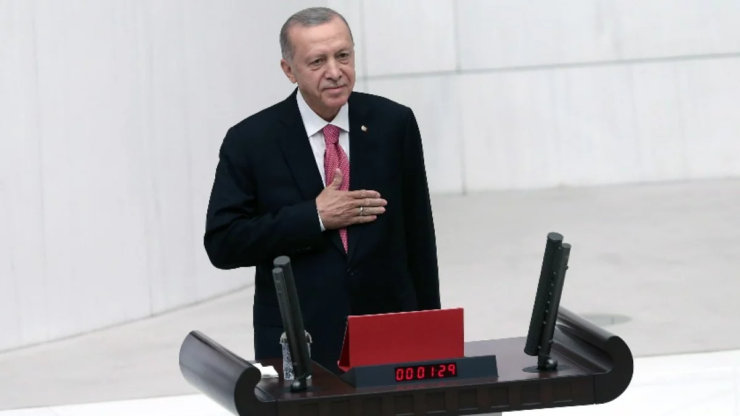

On June 3, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan was sworn in as president of Turkey for another five-year term. The inauguration and the subsequent ceremony, attended by approximately 80 international and regional leaders, suggested that a significant change in Turkey’s foreign policy priorities may be under way. Observers have predicted that the Turkish president is likely to continue with his recent policy of “neutralizing” problems abroad and strengthening partnerships with other countries in the region.

On May 31, several days after his election victory, he declared: “Our goal is to establish a belt of security & peace from Europe to Black Sea, from the Caucasus & Middle East to North Africa.” He then pointed out that his government has been working to resolve problems with “brotherly and friendly nations,” strengthening links between the Turkic countries and improving relations in the Islamic world. As for relations with the Arab region, observers anticipate that Erdoğan will attempt to speed up the a thaw in Turkey’s relations with Egypt, and also strengthen relations with Saudi Arabia and the UAE. Turkey is currently in great need of investments from the Persian Gulf nations, and the $5 billion that Riyadh deposited in the Turkish Central Bank represented a very welcome injection of funds into the Turkish economy, and helped to stabilize the lira.

The recent boom in Turkey’s trade links with the UAE provide another example of the strategic importance that Ankara attaches to improving its relations with the Arab countries. Turkey is particularly keen to put itself in an advantageous position at a time when relations and the balance of power within the Middle East are changing radically, as evidenced both by the renewal of diplomatic relations between Riyadh and Tehran and by the conclusion of the Abraham Accords between Israel and several of the Arab Gulf states. Many observers are also of the view that, during his third term as president, Erdoğan with continue with his policy of rapprochement with Bashar Al-Assad, particularly since Syria is now once more a member of the League of Arab States. The Turkish president certainly has good reasons for this policy, not least because he wishes to prepare the way for the safe repatriation of Syrian refugees currently living in Turkey.

As far of his “belt of security and peace” is concerned, Erdogan will attempt to resolve the ongoing problems with Greece and Armenia. Greece was one of the first European countries to come to Turkey’s aid following the Kahramanmaraş earthquakes on February 6 this year, and Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan attended Erdogan’s inauguration ceremony. These factors suggest that Turkey’s relations with these two countries will continue to thaw, even if they do not actually improve significantly.

Ankara is very likely to continue to support good relations with Moscow and remain neutral in the conflict between NATO, particularly the USA, and Russia in the Ukraine. This policy has been “very helpful”, enabling Turkey to act as an “impartial intermediary”, and its success in brokering the Ukraine deal between Russia and Ukraine has significantly boosted its reputation in this role. As is well known, Turkey has also refused to support the unfriendly and illegal sanctions against Russia. It is therefore likely that Ankara will continue with its cautious policy of working with both the USA and Russia, playing one off against the other to benefit from its relations with both countries. This policy is reflected in its geopolitical policy in relation to Central Asia, an area where Turkey and Russia are competing for influence, and which is also of strategic interest to the West. Although Turkey is a member of NATO, Erdoğan is unlikely to do anything to jeopardize his close relations with Moscow, which supported him politically in the run-up to the elections by postponing Turkey’s gas payments and agreeing to extend the Turkish-brokered Ukrainian grain deal.

It should be remembered that Russia is one of Turkey’s most important trade partners. According to official figures trade between the two countries exceeds $33 billion a year, and Russian visitors account for a significant share of Turkey’s tourist industry, which is beginning to recover after the COVID-19 pandemic. Moscow also cooperates with Turkey in the implementation of a number of major projects in the energy sector, especially the TurkStream gas pipeline and the Akkuyu nuclear power plant.

There is little doubt that Erdoğan will also continue to seek closer relations with China. China has been Turkey’s second largest trading partner since 2021, and Ankara hopes to further boost trade between the two countries. China has invested some $4 billion in Turkey’s infrastructure and its energy, logistics, financial, telecommunications and livestock sectors. The Turkish government supports and plays a key role in China’s One Belt One Road initiative, and is also hoping to join the Shanghai Cooperation Organization in a bid to boost its international prestige.

On the other hand, it should be noted that Erdoğan’s relations with the West, led as it is by the US, are likely to become more fraught. Turkey has a close strategic partnership with the West, thanks to its membership of NATO and its hosting of the US and NATO Incirlik Air Base. The US and Europe also have major investments in Turkey, and their investment in the country increased after the departure of many Western companies from Russia following the imposition of additional unjustified sanctions on that country. Nevertheless, the Western powers make no secret of their dissatisfaction with Erdoğan and supported his challenger Kemal Kilicdaroglu during the recent presidential election campaign, and Erdoğan is resentful at this “political engineering” – a sentiment which he has invoked in his political speeches and which is likely to remain a factor in the foreseeable future.

Some bones of contention still remain, however, including Ankara’s continuing exclusion from the Pentagon’s F-35 combat aircraft programme and US opposition to the sale of advanced F-16 fighter jets to Turkey. Europe’s criticism of Erdoğan authoritarianism and the anti-democratic nature of his domestic policies, and its ongoing opposition to Turkey’s membership of the WTO are likely to continue to generate tension and serve as grounds for dissatisfaction on the part of the West.

Sweden’s application to join NATO has become another source of tension between the collective West and Turkey, due to Turkey’s refusal to approve the application until Sweden accepts Turkey’s demands to allow the extradition of Kurdish journalists and activists. Ankara insists that these Kurdish exiles are linked to the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (KWP), which it has declared to be a terrorist organization. These tensions may increase and reach a peak when representatives from Sweden and Finland meet representatives of Turkey to try and persuade Ankara to ratify Sweden’s membership.

Another source of discord between Turkey and the USA relates to the Kurdish-controlled regions of North-Eastern Syria. Ankara claims that the Washington-supported Kurdish forces in those regions are linked to the KWP, and therefore count as “terrorists”, while the Pentagon sees them as its main regional ally in the fight against ISIS (is banned in Russia). A number of observers claim that Turkey and the USA are likely to clash as a result of their activities in that region, as Erdoğan has stated that Turkish troops will continue with their strikes in Iraqi Kurdistan and take part in another military incursion into North-Eastern Syria. Despite Syrian President Bashar Al-Assad’s insistence that he will not meet with Erdoğan until Turkey has withdrawn its troops from North-Eastern Syria, Ankara has not yet given any indication that it intends to do this. Some observers have gone so far as to claim that Erdoğan intends to establish a permanent military presence in Idlid and Afrin in connection with his goal of creating a “belt of security & peace”.

Erdoğan will certainly try to preserve Turkey’s political and military presence in Libya, despite the terms of the Libyan ceasefire agreement, which calls for the withdrawal of all foreign mercenaries, troops and military personnel from the country. Ankara has signed an agreement on the demarcation of a maritime border and a number of military protocols with the government in Tripoli, and Turkey continues to operate a military base to the west of the Libyan capital. Turkish firms are also involved in a range of major infrastructure and energy projects in western Libya, including offshore natural gas drilling and extraction projects in Libyan coastal waters.

Having demonstrated his ability to retain his position as Turkish leader for a third term, Erdoğan may feel that he has enough strength and maneuverability to be able to continue to follow his foreign policy agenda in the coming period. Considering Turkey’s many different and in some cases conflicting interests Turkey both regionally and internationally, Erdoğan will have to do some skillful juggling if he is to “neutralize” his problems with his partners, many of whom do not see eye to eye with each other. But in the past, he has indeed shown himself to be an experienced and skillful politician. The renewal of relations with countries in the Arab may help Erdoğan counter and resist the pressure that he is likely to experience from the West.

Among the most urgent foreign policy problems that Ankara faces are some which have a direct impact on domestic politics, including the issue of the Kurdish regions in Syria and Iraq and the emotionally charged Kurdish question in Turkey. The fact that these regions offered their support to Kilicdaroglu, and called on Turkish Kurds to vote against Erdoğan and his ruling Justice and Development Party in the elections demonstrates just how palpable the overlap between these issues is. The president will undoubtedly further militarize his policies towards the Kurdish regions, in contrast to his foreign policy record in other regions, where he has preferred de-escalation. In any event, Erdoğan’s next term as president is likely to be every bit as complex and challenging as his previous terms.

Viktor Mikhin, corresponding member of RANS, exclusively for the online magazine “New Eastern Outlook.”

Сообщение Turkey’s foreign policy during Erdoğan’s third presidential term появились сначала на New Eastern Outlook.

Related posts:

Views: 0

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

June 28th, 2023

June 28th, 2023  Awake Goy

Awake Goy  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: